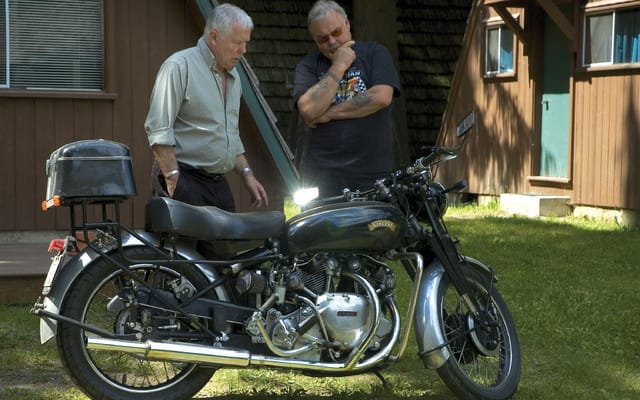

On the shores of British Columbia’s Kootenay Lake, Steve Thornton meets the little black motorcycle with the most legendary of reputations.

If you weren’t tuned to their metallic frequencies, if you didn’t hunger for the curves and knots of their physical forms, or dream of the history and superiority of these Vincent, you could ride past a pair of them and hardly notice. The Vincent, to the uninitiated, is just a little black motorcycle. But for those afflicted, it is a cure. It’s got what you need, and it delivers on its promises.

Glen Breaks didn’t even know what a Vincent looked like, but in 2003 a pair of them at the side of the road stopped him in his tracks. “Growing up, they were the thing, you know? I never saw one, but I heard about them, heard that it was faster than any Harley. It was that myth, so I had always kind of thought about them, and then in 2003, my wife and I were coming back from a trip, we were going up the side of Kootenay Lake, and I saw two bikes. Black, old, English-looking bikes. V-twins.” He turned around, went back and talked to the owners. Brits who had flown a pair of 50-year-old motorcycles across the pond for an international rally and then set off on them for a ramble across British Columbia.

When Breaks and his wife Gina got home, he went online and did some digging, found out there was a monthly journal for aficionados, MPH, and its editor lived 10 miles away. “So I went over and looked at his [Vincent], and I thought, Well, I’ll start looking for one.”

It took him a while, but he found one. A 1947 Rapide, engine number 38, the 38th Vincent built after World War II. It had been originally shipped to the Isle of Malta. There it had been crashed and wrecked, and engine number 38 had been shipped to Scotland and placed in a 1952 frame. In 1980, it was sold and moved to Australia. There it stayed until 2003, when Breaks bought it for $28,000 and had it shipped to Canada.

And as with All Things Vincent, even that part of the story has its twists. “They lost it. It was sidelined in Malaysia for two months and they couldn’t find it. Money was gone, and my wife said, ‘You’re just going to get a box with a pair of rusty handlebars in it.’” But they found it, and in the box was not a pair of rusty handlebars but a full-blown Vincent Rapide, in working order. “I pulled it out of the box, and honestly, I put fuel in it and checked the oil, I gave it one kick, and it started. That was pretty exciting.”

Miraculous is probably more appropriate, but to Vincentophiles, it’s just another day at the office. Vincents are technological masterpieces, and their motors are the hearts of lions, made from melted down Rolls Royce engines and built to go the distance, no matter how far that might be. Even from Australia to British Columbia, by way of Malaysia. Anyway, Breaks’s Vincent Rapide went the distance from his home near Vancouver to the rally site at Kokanee Chalets, a complex of A-frame cabins and campsites on the eastern shore of Kootenay Lake, located on one of the best motorcycling roads in British Columbia, and run by a stand-up comic and motorcyclist who started out with a Hodaka 100 and currently rides a V-11 Moto Guzzi and a Suzuki V-Strom.

Paul Hindson appears to fit nicely into the local culture, which is a laid-back milieu of aging hippie and modern organic privateer, and since he loves motorcycles, he was pleased when a call came in 2008 enquiring about a new location for the Vincent Owners Club’s annual rally. Last year, about 30 Vincents showed up, and they liked it enough to come back this year. Hosted by the Rocky Mountain section, the rally is a smaller gathering this year, just 16 motorcycles: three Black Shadows, 11 Rapides, one Egli, and one single-cylinder Comet. Members have come from the Vancouver and Okanagan areas of British Columbia, from Edmonton, and from a scattering of other locales. One came from Oregon, via California.

Saturday morning, early, the blatt of a big V-twin firing off into the distance announces the day. I set out for a stroll through the campground, camera in hand. Vincents are sprinkled among and between the A-frame cabins and tall cedars, and here and there, owners are having a cup of coffee, a cigarette, a conversation.

Chris Kleps from Oregon has parked his 1950 Egli-framed Vincent in front of his cabin. Its gleaming fuel tank was fabricated in England and it sports English proprietary forks and a Robinson dual-leading-shoe front brake that he says is as powerful as a disc. I notice some scratches on the exhaust that suggest a crash some time in the past. “There was a little sand on the road,” he says. “All of a sudden there I was, watching the bike slide down the road on its mufflers and exhaust pipes.”

The Egli frame is beautiful – and rare: about 100 were made for the Black Shadow motor by Swiss motorcycle racer Fritz Egli in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The bike looks like it’s been on the road – figuratively, but also literally, what with those scratches on the mufflers. It’s a little dirty, a little scuffed. “It’s got 2,200 miles on it since I washed it last,” Kleps says. He’s the guy who came to the rally by way of California.

I stop at a cabin where three gentlemen are sitting near a box of crackers and a bowl of grapes: Richard Vanderwell, who “oiled the highways from Edmonton” on his ’47 HRD Rapide, Ron Peers, who rode his ’47 HRD Rapide from Merritt (coincidentally, where I’ve come from), and Barrie Howell, who came from Winfield in the Okanagan and doesn’t currenly own a Vincent, but has racked up enough mileage to remain forever a member of the clan: he bought a Vincent in England in 1971 and thereafter rode it around the world; when he sold it to his son-in-law it had 590,000 miles on it, and it still ran.

I ask these three men the central question, Why Vincent? The answers pile on top of each other, and I don’t know who said what, exactly. “It was the superbike of the ’50s and ’60s. And the reliability is twice what any other British one was. There’s no question about that. Well, if you took a BSA on a thousand kilometre ride, you’d never get to the destination. The Vincent is immensely superior. So if it’s highways, you’re going to get to wherever you’re going. And you’re revving a lot lower, bigger motors can rev slower, so instead of going along at forty-five hundred rpm on a Triumph or BSA, you’re at twenty-five to twenty-eight hundred rpm. Melted down Rolls Royce engines. You can quote me on that. I made that up.”

As we talk, Tony Cording rides past on his 1950 Rapide. Cording was western regional sales manager for Yamaha Canada until he retired a few years ago. His motorcycle was originally purchased by one Albert Billy Enfield, whose wife was a Motor Maid and who in the mid-’70s chromed the living shit out of it. It went through various owners after that, until in 2005 Tony bought it, removed most of its chrome plating, and engaged in a “complete restoration” with the help of fellow club member John McDougall, who rebuilt his engine and is credited by other members of the club for lending considerable expertise in the reconstruction of Vincent motors. Among those Vincents that are ridden on the street, says Cording, McDougall’s own Black Shadow is “probably the fastest Vincent in North America.”

Cording’s own history is similar to that of other members. He fell in love with the fastest motorcycle in the world when he was a teenager. When he grew older, he wanted one. When he grew old enough and rich enough, he bought one, in this case, for 21,000 American dollars.

It’s a common theme around this campfire. These guys have paid as much money as you’d pay for a new Gold Wing or Electra Glide, sometimes considerably more than that, and often for motorcycles that would be over-rated by the term “basket case” and that were located on another continent.

Perhaps the most beautiful motorcycle here is Howard Sadler’s 1937 Comet, a 500 cc single that he trailered from Victoria. It’s running, but it’s only a 500, and it’s 72 years old, and Victoria is a long way from Gray Creek.

Sadler has six bays in his Victoria home, filled with Vincents. He says he didn’t intend to collect so many, but he has this little machine shop, and he likes making things out of metal that fit onto his motorcycles, and there’s just this little piece of heaven in that shop when he’s alone with his Vincents and his lathe and the smell of burning steel.

Later that day, Paul Hindson (the stand-up comic/campground manager) lends me his V-Strom and we take a little ride along the highway that leads down to Creston. It’s a windy, scenic stretch of pavement that would please the most hardened motorcyclist, and Paul leads the way on his thundering Moto Guzzi. Soon, we catch up to a Vincent, some guy who’s out for a solitary ride. Paul passes him, but I linger behind, catching the melody of this 60-year-old motorcycle that drifts back to me. I stay that way a long time, listening to the crackling roar of the Vincent, watching it bend into the curves. It sounds authoritative and powerful: if James Earl Jones were a motorcycle, he’d sound like this. Suddenly, the Vincent pulls out to pass another vehicle, and it makes no bones about it. In a couple of seconds, it’s gone.

Sunday morning, I watch one or two Vincents leave the campground. Many of them – perhaps most – are riding home, to Edmonton, to Oregon, to Vancouver. I get on the motorcycle I have brought, something brand new this year, a bike that many of these Vincent owners have politely enquired about, but that has none of the steel guts of a Vincent. A couple of hours later, I’m on the Monashee Pass highway, heading through mountain forests, and there’s a Vincent ahead of me. Glen Breaks and his wife Gina are riding home to the Vancouver area on that ’47 Rapide that got lost in Malaysia and then fired up on the first kick out of the box. Glen rides with confidence, and his wife looks comfortable on the back. The bike leans into a corner, much like a CBR600 or a Ducati 1198 would do, calmly, comfortably, as if it was made for this, as if it was fulfilling some sort of destiny.