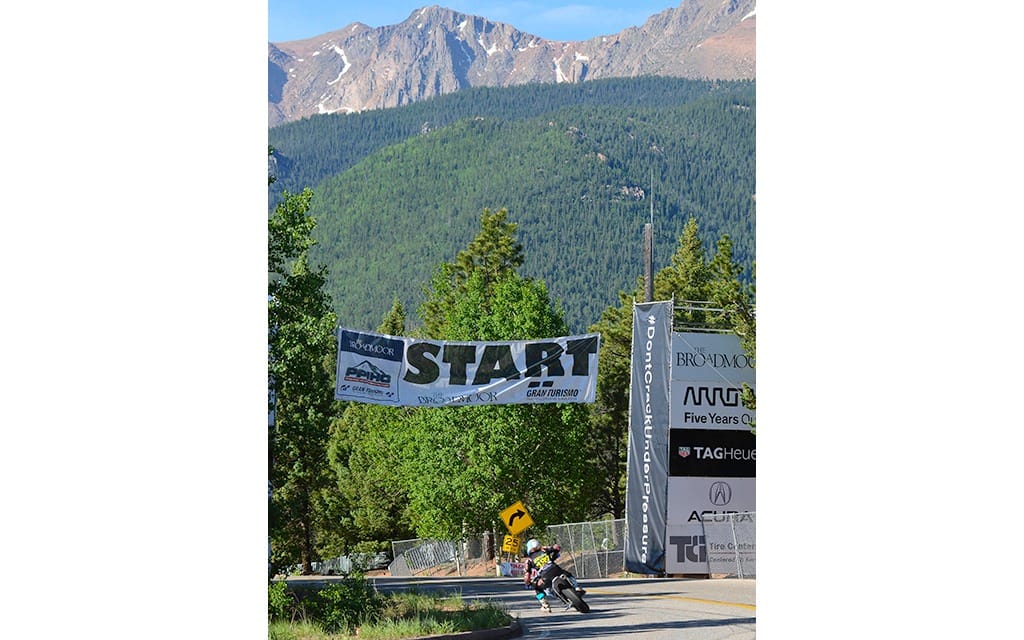

For the 100th running of the Pike’s Peak International Hillclimb, the world’s best become teachers of the hopeful

“You come in through to the bottom of this wide open, it swings you out to the outside here, you’ll come and be on this white line, full gas. Roll it off a little bit, trail brake . . . come in to the inside, you almost touch your knee on that curb, swings you back out across this stuff, the tar gets really loose so you start to undulate a little bit right here, you’ll swing it back to the outside, turn in late, come in, tap the white line, all the way out, tires are almost touching those hay bales, wait, turn in, knee into the grass, grass grass grass, flick it up, try to wait a little bit, come in and bring it as close as you can to the curb, because when you hit that little bump, you wheelie, your pegs almost touch that, and then you’re back and in between that tar stripe and the white line. That whole section just happens. You start it, and the next four turns are just what come because of it. You’re going through it so fast it’s linking them all together.”

—Carlin Dunne, King of the Mountain

Ten minutes. About the time it’ll take you to read this story. And a nearly unreachable goal for motorcyclists competing in the Pike’s Peak International Hillclimb. Six hundred seconds, 12.4 miles and 156 turns, rising nearly a mile up the side of a Colorado mountain. On pavement that’s been savaged by winters at altitudes that can make a Toronto boy need to sit down and eat a doughnut.

If you look up from the starting line at 4 a.m. you might notice a small red light hanging in the sky. That’s the finish line. It’s 14,115 feet above sea level, and after Carlin Dunne drove us up there from the 9,390-foot starting line around midday, I climbed out of the car, felt the cold air on my face, and became dizzy. It wasn’t just me; others in the car—Alyssa Roenigk, a writer for ESPN the Magazine; freelancer Jeff Jablansky; and our host Michael Haas, who works on the PR team for Ducati North America—felt the elevation. Dunne seemed unaware of it—but he’s been there before; Dunne and only two other motorcyclists have broken through the 10-minute barrier at Pike’s Peak. Those two are Greg Tracy and Jeremy Toye.

Toye raced this year and came in first in his class aboard a Victory Project 156 bike with a time of 10:19.8. Dunne, whose sub-10-minute run on a Ducati Multistrada in 2012 is an all-time motorcycle record, and Tracy, who clipped 10 minutes on the same model in the same race, did not compete this year; with two other Pike’s Peak winners, Micky Dymond and Gary Trachy (Greg’s brother—never mind the spelling), they were Squadra Alpina, a safety and coaching team operating under a new Ducati program called Race Smart. This year, for the 100th running of the Pike’s Peak International Hillclimb, Ducati North America has declined to race as a brand, but has instead brought together these four riders—each a former Pike’s Peak winner—to help motorcycles (any brand) perform successfully in one of the most dangerous and difficult races in the world. The Squadra Alpina members were given 2016 Ducati Multistrada Pikes Peak models to ride when working with the competitors, trying to drill into them the right lines for a quick and safe passage up the mountain.

“The amateurs just want to go fast,” Dunne told me before the race. “Some of them memorize the name of every corner.” He laughed. “I don’t know the name of every corner. I know how to get through them.” Dunne made up his own names for the corners, but he wouldn’t tell us what they are. “I don’t think you could publish that.” He said there are “about 40 turns that can hurt you—you learn those, not the rest.”

But during the half-hour drive in an SUV up Pike’s Peak on the Saturday before the June 26 race, Dunne kept up a monologue that didn’t stop, describing what happens on his motorcycle at every single one of the 156 corners. There may “only” be 40 corners that can hurt you, but Dunne (who does know some of the approved names of corners) understands the pavement, the way the bike reacts to it, and the speed at which he can get through every corner, not just the bad ones. And there are so many corners that it’s a challenge to even know, at racing speeds, which one you’re coming into.

“This is one of the biggest mistake corners on the course, because they mistake it for the last one. People come into this wide open, they don’t realize which turn it is. Before, they’d launch into these trees, but now they have hay bales, they have the air bag here. It’s called Engineers. It’s a really slick corner as well. And you flick out of it so hard, there’s such a big transition that the bike will tuck, and you almost crash it right here. It’s really kind of sketchy because in this corner the edge comes up really quick, so you run it out almost to the outside edge, your tires are on the white paint, you pull it back on the inside here, and you’re going so fast that all of a sudden you’re on the outside. Then you’re back on the inside. It’s just one big corner, so it’s like the yellow line snaking left and right under your tires, and you’re linking these together. If you’ve carried your momentum well, you’re wide open coming up through this, this is called Picnic Ground—people are lining the road, it’s kind of cool though ’cause you can see everyone, just screaming, yelling, through this. Braking zone starts about here, and it’s full brake, rear end up in the air, brake brake brake, trying to get it to slow down. Jeremy Toye crashed into that qualifying a couple of years ago.”

After the drive up the hill, we piled out of the car and visited the doughnut shop, some of us feeling a need to sit down. That was where Dunne and Tracy sat in 2012 to await their results. The race was dramatically different that year, the first hillclimb since the City of Colorado Springs finished paving the road in the fall of 2011. In 2010, Tracy won the 1205 cc class on a Multistrada with a time of 11:46.6. In 2011 Dunne won it, also on a Multistrada, in 11:11.3. In 2012, they faced a course that was entirely paved for the first time, and they knew they could run fast, that one of them was going to win.

It was an all-or-nothing kind of race. At Pike’s Peak, you don’t run against the other guy; you race against the mountain, and the timing clock (and your arrival at the finish line, which is by no means assured) tells you how it went. Tracy went first, followed soon by Dunne. At the top, they waited for their times, because of some problem with the timing system unable to get the numbers quickly. When the information finally got to them, they hugged. Tracy had done it in 9:58.262, forever the first motorcyclist to break through the wall. But Dunne’s time was 9:52.8. Dunne was named “King of the Mountain,” and his record has not been threatened since.

At a barbecue dinner for the team on the Saturday before the race, I asked Tracy what it felt like to make that run. “We were really pushing it,” he said. “When you go that fast, you’re at 100 percent focus. If you push it that hard, take that risk, and you make it, you really know you’ve done something.” He remembered the two of them looking at each other when the results came it. Each had ridden so hard on such a treacherous road that a mistake of an inch or two at a hundred miles an hour could have been lethal. Would he do it again? “I think so, yeah,” Tracy said.

Sunday, June 26, 3 a.m. The alarm on my iPhone doesn’t sound quite so hostile now that I’m used to early starts. Qualifying and race mornings at Pike’s Peak start dark and early.

The sky is dark, but Pike’s Peak Highway is lined with cars that move so slowly I could have walked ahead. It takes forever to get through the park gates (Pike’s Peak is part of Pike National Forest), but then we speed up. By 5 or so we’re at the gathering area near the start line. There are bikes parked here and there, cars of all descriptions. People getting ready. One guy on an MT-07 Yamaha has come from Brazil just for this. A Japanese team with an exotic 4-Motor EV Concept car charges the battery pack, feeding dry ice to it to keep the batteries from exploding. The race will start at 7:30, so I make plans to get where I can shoot. But as the day slowly brightens, it becomes apparent that this will be difficult. A squad of cops stands near the start line, next to a huge Homeland Security truck, ready to prevent anyone from leaving the spectator area. I sneak off through the trees and begin climbing.

Half an hour, maybe 40 minutes later I come out of the trees to the edge of the highway. A good curve lies in front of me, another behind me. I can get them transitioning. I sit, make the camera ready, and wait.

And wait. The start is delayed for ice on the road up near the summit. The sun must first get high enough to burn it off, or at least change its state. After an hour or maybe two, I hear an approaching roar. The sun is well up now, the air warming. I get ready, aim the camera at a point in the road, and then there’s a bike coming, the rider leaning hard. I shoot, shoot, shoot, and the bike is past me. A minute later, there’s another.

The electric bikes are the freak shows, storming up the mountain with a wailing siren, or nearly silent, they take on Pike’s Peak with the muscle and agility of the gas-powered bikes, but there’s a sense of other-worldliness about them. I shoot. Listen for the howl of a distant early warning device or the snap of an internal combustion engine. Shoot, sweat, eat the M&Ms that Haas, what a guy, has bought for me. Too soon, it’s over. The sidecars come through, then the quads, and then it’s cars.

In the end, Bruno Langlois was fastest on a motorcycle, riding a Kawasaki Z1000 to the top in 10:13.1 to win the Heavyweight class. Moto-journalist Don Canet, on a Victory Prototype electric bike, was the second fastest motorcycle rider, doing it in 10:17.8. Toye was third on a gas-powered Victory, and about 30 others followed them, getting times in the mid-10s or longer, up to nearly 13 minutes. Rennie Scaysbrook, one of the rookies coached by Squadra Alpina, finished in 10:28.4 on a KTM Super Duke 1290R. Marcel Irnie, a Canadian and another rookie coached by the Ducati team, rode a Zero to the top in 11:31.3. That Brazilian on the MT-07 made it in 11:30.5.

It takes me 40 minutes to hike back down to camp, where the Squadra Alpina boys are lounging, signing autographs, taking it easy. Relaxed. You can tell, though, that they’d rather be racing.