High roads in the Alps are motorcycling nirvana, if you’re prepared for them

I ascribe to the Christopher Hitchens theory of religious devotion. God is Not Great. However, if I were to be converted to the flock, I think my holy sanctuary would be atop the Grimsel Pass in Switzerland.

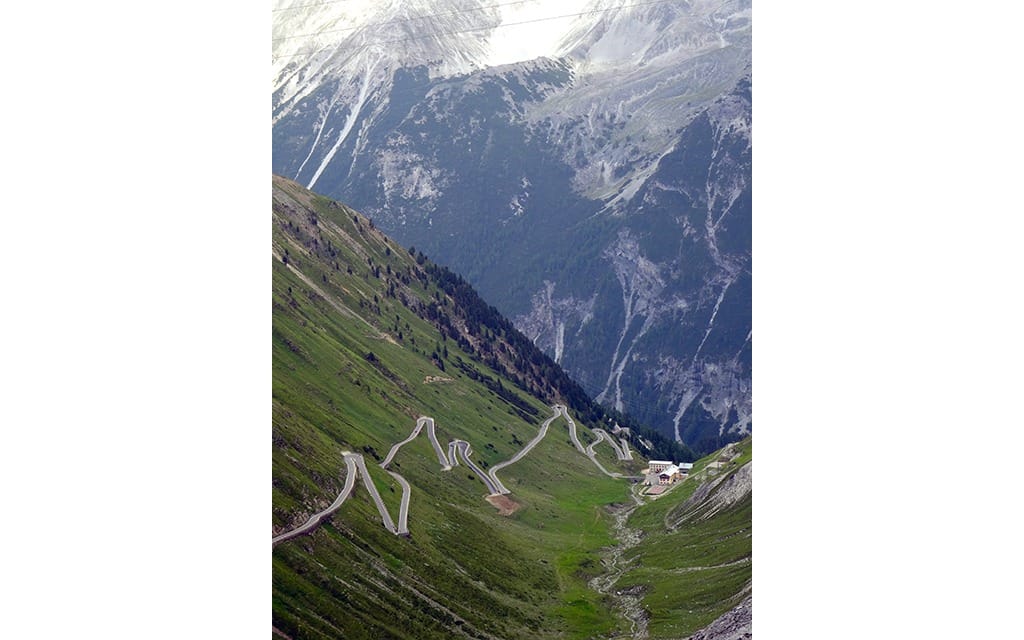

Or maybe the Furka. Perhaps even the Neufenen. Certainly, the Stelvio—all 53 peg-grinding hairpins of it—is worthy of worship. Indeed, if motorcycling be a religion—and riding a two-wheeler is the closest I get to spiritual enlightenment—then its altar is somewhere between Andermatt, Switzerland—centrally located in the middle of the famed Furka, Neufenen and Grimsel passes—and Bormi, Italy, home of the legendary Stelvio Pass. There is simply nowhere else in the world—at least where I have ridden—that combines the majesty of glacier-covered mountains, roads so serpentine you will swear they were designed by Kenny Roberts, and a local population that is, unlike anything you’ve ever experienced here in North America, vociferously welcoming of motorcyclists.

Spiritual enlightenment does require certain terrestrial practicalities, however, and, truth be told, the average North American rider is woefully ill-equipped for some of the rigours of Alpine riding. In fact, the experience is so vastly different that my first recommendation, for even the most rugged of individualists, is that they at least contemplate joining an existing adventure travel group to get the lay of the land. Edelweiss is the most experienced in the field (their magazine ads used to feature a picture of the back end of the Stelvio) and they offer both Alpine Academy and Alpine Extreme. Their tours are extremely well organized, offer both packaged routes and some semblance of freedom to choose from and, perhaps the biggest boon to the nervous first timer, the lodgings are all pre-booked. That said, halfway through my one—and only—organized tour, I was ready to split for parts unknown, having quickly determined that pre-packaged and adventure were oxymoronic when it came to motorcycle touring. Besides, Edelweiss prefers the Austrian Alps and I am very much prejudiced towards the Swiss/Italian variety (besides the superior hairpins, the cuisine is, big surprise, a whole bunch better).

So, where does one start to plan such an adventure on your own? Which of the seemingly countless passes should you ride? What bike is best suited to the diverse requirements of Alpine travel (i.e. comfortable enough to endure the autobahn or autostrada to get to the twisty bits, spry enough to clamber up them)? Where should you stay? Even the question of when to go (some passes don’t open up till June) requires some planning. And the type of riding gear is critical. Indeed, I always caution anyone joining me on these adventures that what you wear is actually more important than what you ride. And how much gear to bring, especially if you’re touring two-up, is always going to be a difficult compromise.

In fact, all of the above are very much intertwined. For instance, which passes you might navigate will be determined, at least in part, by what you’re riding. Are you heading over solo? Or riding two-up? Experienced and thoughtful veteran, or rank novice? The line between happiness and calamity could be as fine as having the right bike going in the right direction up specific passes. Large touring bikes, top-cases and saddlebags loaded to the gunwales and passengers further weighing down the back end, are always happier heading down a mountain pass than going up. On the descent, the steep decline puts more weight on the front tire, the extra traction and compressed forks allowing more secure braking into seemingly endless switchback turns. You can, if you’re so inclined, chase sportbikes down a mountain pass on a fully-loaded BMW K1600 GT and not embarrass yourself.

The same road up, however, can turn that same fine-handling sport-tourer into an unwieldly chopper, again especially if a passenger is biasing the weight distribution to the rear. The steep incline—10 percent grades are not unheard of—exacerbates that already rearward weight bias and there’s precious little feedback from the front end. That same semi-sprightly K1600 can turn into quite a handful going up the eastern side of the Stelvio, especially on the tighter radii right-hand turns.

Solo riders, especially those who’ve wisely chosen some form of adventure touring bike, will find just the opposite. Heading down is not nearly as fun as heading up and you’ll find the local heroes—more often than not KTM mounted—flying up those mountains, their pace seemingly not far off Joey Dunlop’s at the Isle of Man.

What that means, in practical terms, is:

1) If you can, always choose the lightest bike possible. An adventure tourer—like BMW’s famed R1200 GS, Triumph’s Explorer or Honda’s new Africa Twin—will be more fun in the mountains than even the best sport-touring mount, their slight sacrifice in open-road comfort more than made up for by their ease of handling. If you’re riding solo, don’t immediately discount 750s and 800s in favour of litre-plus rides. Many North American first-timers, especially those with some experience, make the mistake of bringing their bigger-is-always-better mentality to the Alps; it simply doesn’t apply. If you and/or your passenger can stomach the smaller storage capacities and lesser wind protection offered by smaller displacement mounts, do so. You’ll thank me later.

2) If you are riding a big touring bike, choose the easier side of the pass for the ascent. For instance, avoid going up the aforementioned eastern side of the Stelvio if you’re two-up; approach it from the west instead. Load some gear, if you can, in a tank bag for more even weight distribution. And even you experienced riders out there, practice making almost full-lock turns on your own touring mount back home, doing so on the steepest, bumpiest incline you can find, because the most treacherous part of any Alpine pass is not its peg-grinding, high-speed sweepers, but the 10 km/h uphill switchbacks.

3) Don’t treat warnings of the difficulties of riding the passes as trivial (again, especially if you’re two up). The Grimsel Pass, for instance, is very sport-tourer friendly (it’s also the most scenic in my not-so-humble estimation). But the Splugen? Not so much. First timers, should they be cautious, should be able to navigate the Grimsel, Sustenen, Obler, Julier and Majorca and even the Stelvio (remember, up west side, down east side) passes without much trepidation. The San Bernardino has its challenges, the aforementioned Splugen will scare rider and passenger alike with its incredibly steep drop offs. And, if you should ever get caught on the Tremolo on anything larger than a scooter, save yourself the grief of a frantic 911 for help and turn around right away.

4) As strange as this sounds—especially coming from someone whose entire wardrobe consist of black T-shirts and faded jeans—what you wear is actually more important than what you ride. Yes, you back there shaking your head in disbelief, it is.

Not only should you wear something protective—the now world-renowned CE armour designation comes from Europe for a reason—but the same clothing (unless you’re going to devote all your precious cargo space to nothing but motorcycle gear) must accommodate some fairly extreme temperature and climate fluctuations.

If your starting point is some Italian port of call, for instance, there’s a good chance that the mercury could hit 35 degrees Celsius, baking any fully leathered-up biker. That same day, should you have climbed atop the Stelvio (at 2,757 metres, the second highest paved pass in the eastern Alps), the temperature, sun still blazing, could drop to less than eight degrees Celsius. And, if you are doing a serious Alpine tour, at least part of your time will be spent in torrential downpour. You can go from baking to frostbitten in two hours.

Essentially, then, you need complete three-season comfort. From prior experience, leather jackets—vented or no—don’t cut it. Anything above about 28°C turns any non-mesh jacket into a sweatbox, perspiration turning to icicles at the peaks. Ideal is a three-layer jacket, something with a mesh exterior and separate Gore-Tex and Thermolite layers. Separate water- and cold-proof layers are highly recommended because jackets combining both rain and warmth layers will be compromised (at the base of the mountain it may be hot and sweaty while, at the top, if it is rainy chances are it is also seriously cold as well). The best solution I’ve found is Olympia’s AirGlide jacket, but any mesh clothing with separate rain and warmth layers will do. Also make sure your gloves are Gortex lined as your hands will be the first things to get wet and chilled and, similarly, lined-leather boots are also essential.

6) Even things as seemingly simple as directions are worth preparing for in advance. Having a GPS system—Garmin or otherwise—is a tremendous bonus, but they can be a nuisance when trying to navigate to the passes. As you get closer to said passes, most will try to circumvent these time-consuming twisty roads at all costs. So, even if I have access to a modern GPS system, I always bring a map.

Here, too, you’ll find there are very specific needs for an extended motorcycle tour. The problem is that most locally-available maps are country specific and since the passes tend to criss-cross borders frequently, using multiple maps becomes a real hassle. Alpine-specific cartography is available, the best I’ve found being Hallwag International’s Alpine Countries. Unfortunately, the only local place I’ve found to buy it is at the top of the Stelvio Pass so it may be better to order through www.mapsonline.co.uk or some other map supplier.

7) Another major source of trepidation—at least before your first sojourn abroad—is booking hotels. Where to stay, how much to budget, and how much lead time is necessary to ensure accommodation are all realistic worries for the first-time Alpine adventurist. The good news is that, as a firmly committed seat-of-my-pants traveller, I can attest that the chances of getting caught out without vacancies, wherever you might be, would be very low. Hotels are to be found in every little burg along virtually every route, and if you really want to get the full Alpine experience, atop most popular passes.

As well, virtually all are biker friendly, many openly courting bikers with some long-past-due-date relic of a Kawasaki or Suzuki perched in their window, on their terrace or even atop their roof. If you’re taking my choice of Swiss-Italian passes, then starting in either Andermatt or Bormio (heading in either direction is fine; I chose my starting point according to the predicted weather just a few days prior to departure) offers an incredibly scenic and rustic place to start your journey.

If you’ are starting in Bormio, I’d recommend the San Lorenzo (www.sanlorenzobormio.it). Fairly priced, it offers service beyond compare and even a secure underground garage for stowing your bike. If you’re travelling two-up and feeling just a little romantic, I recommend the Tower suite with its shower in the middle of the room and two balconies from which to view the Stelvio Pass. It’s among the best rooms I have ever laid head to pillow in. If your route starts in Andermatt, try the 3Konige & Post (www.3koenige.ch). Pricier and a little less luxurious than the San Lorenzo, it’s nonetheless the best anyone poorer than Warren Buffet can afford in Andermatt. (Andermatt is a popular tourist destination so the 3Konige may be one lodging you need to book in advance.)

And, finally, my best advice is to allow yourself some time. The Bormio to Andermatt route via the Selvio, Splugen, San Bernardino, and St. Gotthard’s passes route can be done in about two and a half days if you are ruthlessly efficient. Indeed, my record, on a particularly frenetic Alpine blitz, is 13 passes in just three days.

But that misses the point. These are, in my opinion, the greatest sights to be seen on the best roads a motorcyclist will ever ride among the friendliest—and surprisingly motorcycle savvy—people in the world. You will, I promise, find yourself at the bottom of a pass wanting to ride back up it immediately just to savour motorcycling as it always should be. The best advice I can give you, then, is to allot more time than you think is necessary to revel in all this beauty.

Who knows, maybe we can start a new religion.