Risk versus reward writ large

Trevor Daley has been driving for hours. We started in Mississauga, Ontario, and after dinner an hour south of Sudbury, I offer to take the wheel. But Daley says he’s OK and keeps driving all the way to Sault Ste. Marie. I doze fitfully as twilight turns to night, perking up when we pull into a gas station. Daley looks haggard while working the pump. “Can you take a shift?” he asks. My first stint behind the wheel starts sometime around midnight and within minutes I’ve driven the unfamiliar truck through an immense pothole. There’s a crash as a rear wheel hammers the hole, then a clattering of items falling in the back of the truck. I cringe, hope I haven’t damaged his race bike, and apologize. “Don’t worry about it,” he says with a sleepy smile. “You didn’t pave the road.”

Earlier that day, when I enter Daley’s one-man-operation motorcycle shop, I see trophies, shelves cluttered with them. They’re from his racing exploits, both two- and four-wheeled (before joining the Canadian Superbike Series as a rookie amateur in 2011, Daley was a successful kart and car racer and professional car racing mechanic). Walking into the room bristling with silver and gold statuettes you’re entering more than a motorcycle shop. Onespeed Chop Shop is a shrine to speed. And to vanity.

Battered leather race suits hang on a rack by the door. The nearest, from the 2014 season, when Daley finished runner-up in the pro superbike class, is ground down on the knees, elbows, and shoulders. The back of the suit looks like it’s been run over with a belt sander. Daley crashes. All fast guys do. But — the trophies prove it — he’s a finisher, too.

There’s no receptionist at the desk. (“I’d rather spend money on racing than employees,” he says later.) I call his name, though I doubt he can hear me over the din of heavy metal music coming from the shop. Peeking around the corner, I spot him sorting engine bits on a workbench. We’ve never met, though he grins like we’re old friends. “Hey man, nice to meet you,” he says. It’s a shop-worn phrase, but he makes it seem genuine. I reach out for a handshake. He holds both of his hands up and shrugs as if resigned to being handcuffed. “My hands,” he says apologetically. I assume they’re covered in grease. Then I remember the summer he’s been having.

Daley broke both hands — horrifying for a racer and a man who makes his living with his hands — in early June during a pre-season testing crash at Calabogie racetrack, just a week before the season was to begin. To add to the misery, Daley had enlisted — or so he thought — the assistance of tuner Gary Medley, a mechanic with AMA and World Superbike experience. But Medley was a no-show at the test and didn’t set foot in Canada all season.

Two broken hands on the eve of a race would sideline most. Not Daley. He loaded his truck by himself and drove to Calabogie for the opening race. Torrential rain dashed Friday’s practice but on Saturday Daley was 10th fastest, which admitted him to the final qualifying session. On his first flying lap the chain snapped and punched a hole in the crankcase. Without a crew and with mangled hands, Daley stayed up overnight and swapped in the engine from the GSX-R he’d destroyed the week before. (Many helpful hands emerged from the darkness, including good-guy pro Ross Millson and tuners Hervé Remetter and Jeff Bloor. Neil Graham proved his worth by holding the flashlight.) In Sunday’s race Daley made it to sixth position but tangled with rider Tim Robinson and crashed. He remounted and finished 12th.

Two weeks later, at the series’ second round at St. Eustache, Daley arrived with U.S. tuner Dave Weaver, who’d become available when his rider, Larry Pegram, was out of a job after Eric Buell’s EBR World Superbike team folded. Daley qualified sixth and, in a downpour, was running third before crashing spectacularly on the front straight. “I hit a pool of standing water and the front was instantly gone,” he says. He ran down his bedraggled GSX-R and remounted, limping over the line in ninth.

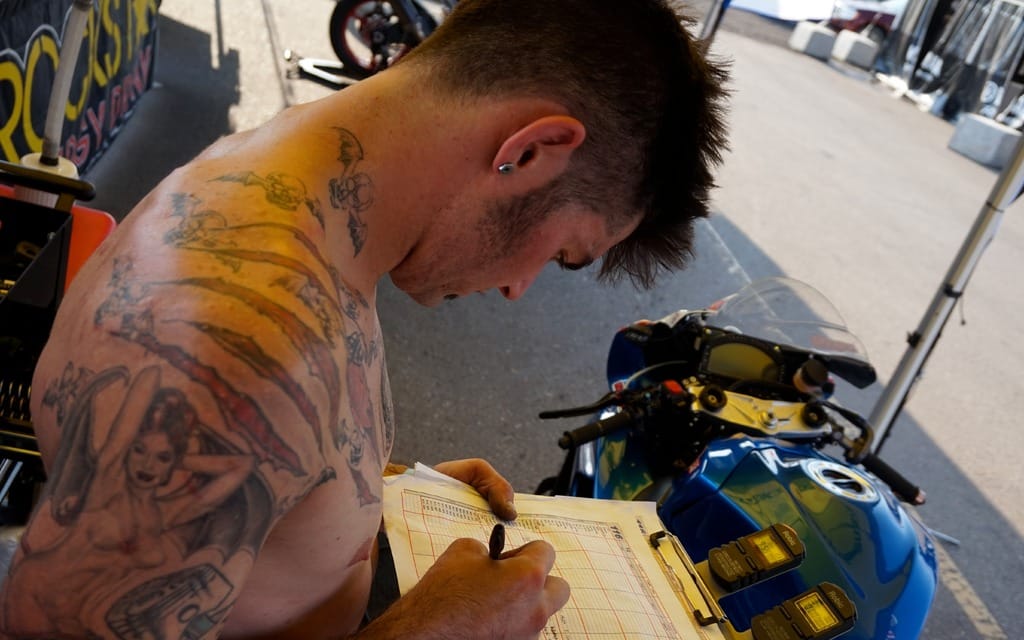

All that battering — compounded by incomplete healing and a job that taxes his digits — has given Daley the hands of a bare-knuckle boxer. At rest they’re perpetually folded, like he’s loosely cradling two Fabergé eggs. He says that even with surgery, which the 29-year-old has elected to forego (with a shop and race program to run, who has time?), his hands would likely torment him for the rest of his life.

Which brings us back to Sault Ste. Marie. I’m here because I need a story and Daley needs a hand driving to Edmonton for the race that begins in a few days. Daley’s original plan was to fly west while his father left a week early to drive the truck, an aging Ford turbo diesel stuffed to the skylights with bikes and equipment. It didn’t work out that way — his father’s licence was revoked after he was charged with driving under the influence of alcohol. But before we can get to Sault Ste. Marie we must leave.

Departure was slated for Monday, at noon, but when I show up his Suzuki is perched on a lift. “I just have to finish putting the stickers on,” he says. As he slices and shapes the sticky plastic around the fairing, I scan the shop. It’s mostly tidy, save a scattering of empty Rockstar energy drink cans. (No surprise there; I’ve heard of his affinity for the stuff — plus they’re a sponsor.) For someone whose blood is one-quarter caffeine, he’s surprisingly mild-mannered and soft-spoken as we chat. Stickers done, we finish loading his gear (including 72 cans of Rockstar in stomach-churning flavours) and leave at 3:30 p.m.

Daley takes the first shift driving and we rumble north on Highway 400. The Ford is loud, incessantly so while passing or labouring up inclines. Raising our voices over the racket, we realize we’re the same age and have nieces we dote on. Daley is an adoring godfather. He beams beneath his oversized sunglasses when speaking of his “little girls.”

Though we hadn’t met, I knew — or thought I knew — what Daley was all about. In the Onespeed booth at a 2014 motorcycle show, he showed off a custom cruiser to a ballooning crowd flanked by blondes in extremely short shorts that had the words “Got Ass?” across the buttocks. His booth was the busiest at the show. I also knew he was a superbike racer. From then on the name Trevor Daley evoked images of nearly naked women and fast bikes.

Daley may have been without a crew and lacking the proper use of his hands at Calabogie, but he didn’t overlook booking a pair of women to adorn his pit and to hold umbrellas on the starting grid. Come on Trevor — do umbrella girls really have a place in modern racing? He considers the question while scanning the road. “Some people say no, but it’s just part of the show, and a lot of people still respond to it. Part of why we’re here is to entertain the public and promote our sponsors. Some people think it exploits women, but isn’t it actually exploiting the people it appeals to?” A few minutes later Daley guides the truck to an exit. It’s dinnertime, and I’m about to meet his mother.

Julie greets us outside a cottage on the French River, and gives her son a lingering hug; the kind that says it’s been a while, that she’s been worried. As dinner is prepared, Daley shows me the bunk his brother shoved him from. (The fall caused his first concussion. He’s now at 13, and counting.) We dine on a back deck overlooking the river. The setting sun colours the sky a soft pink. It’s quiet and peaceful, though tension is palpable between mother and son. “You should visit your grandmother,” Julie says. I assume she means at a later date, but Daley stands and strides toward the cottage next door. His grandfather died recently, Julie says, and his grandmother has cancer. I ask if she watches her son race. “I used to, but I can’t watch anymore. I’ve seen him crash too many times.” Daley is solemn when he returns and we get back on the road.

The truck. The steering is slow and the brakes mushy. It’s a creaky, ponderous beast that’s roared over 400,000 kilometres. The CD player is broken. The radio works, but the display is only partially legible, like it’s written in Predator script. After I take the wheel in The Soo, Daley falls asleep. Wawa and White River pass as dimly lit bubbles in the blackness. Fog as thick as milk rolls in off Lake Superior and the road slithers into the gloom like a garter snake disappearing beneath a bush. It’s a shame to drive the North Shore, the most sweeping and scenic part of the trip, in darkness, but my only concern is keeping my eyes open and the rig on the road. By Thunder Bay I’m beat and Daley takes over. It’s 7 a.m. on Tuesday.

Our schedule is set: one rests while the other drives until he can drive no longer, and then we switch. When we’re both awake and alert we talk of racing, of bikes in general, of other interests. (Daley loves the History Channel, WWI and II documentaries especially.) When tired, we sit in silence. Daley considers aloud his paddock set up, his initial bike settings, his strategy for the weekend, and what jobs he needs to catch up on when he returns home. This is how his brain works, like a computer with too many programs running at once. The problem is that you risk a system crash. Mostly, his energy and enthusiasm seem boundless, but occasionally he becomes sullen and withdrawn, his gaze vacant until something reboots within.

After finally exiting Ontario, which stretches on forever in maddening sameness, we pass through elation and exhaustion. The excitement of reaching Manitoba fades when we realize how far we’ve yet to go. Flat farmland seeps to the horizon. At Bloom we turn north on Highway 16. Jubilance at the Saskatchewan border is blunted by the fact that it’s Saskatchewan. Daley finally calls a halt in Lanigan at dusk. It’s 9:30 p.m. We’ve been on the road for 30 hours. Bone-weary, we collapse onto motel beds.

Daley is chipper on Wednesday morning, eager to reach the racetrack. The six-hour drive feels like a jaunt after the slog we’ve endured. We arrive and are guided to Daley’s paddock parking spot by series’ staff. We begin to unpack but there’s a problem. Organizers have miscalculated the space needed for an adjacent Honda display. Daley is asked to move. It’s not a big deal, except it could be.

Paddock parking is not at random. There’s a hierarchy, a pattern loosely based on class and prominence. Top pro superbike riders, most of whom have sponsors to please (and egos to sate), are typically placed in high-traffic areas. Daley, who was a late evening arrival at the season opening Calabogie round, was parked in a second row location he deemed inappropriate. He was furious. Now, when asked to move, he shoots me a here-we-go-again look. “Where would you like me to go?” he asks, politely.

After relocating, final set-up, and tech inspection, we check into the hotel. I claim the pullout while Daley takes the small single bed rolled into the room. The tempting queen-sized bed is reserved for tuner Dave Weaver, who arrives tomorrow. Daley turns on the TV and finds the Discovery Channel. “It’s Shark Week,” he says, before falling asleep with the TV on.

After Thursday’s test session Daley complains of front-end chatter. We’re having dinner with Weaver, who just landed. Though I’m familiar with basic motorcycle setup, these two speak a technical language I struggle to comprehend. It doesn’t help when Daley douses his penne Alfredo with HP steak sauce, utterly distracting me from Weaver’s proposed technical solutions. Daley catches me staring at the HP bottle. “I love this stuff,” he says before turning back to Weaver. I’m bewildered, but they’re perfectly in sync. While Daley’s in the washroom, I ask Weaver about their relationship. “I’ve never worked with a guy who builds his own bikes and works on them full time,” he says. “I think it takes focus away from just riding the bike.”

On Friday they sort the chatter and Daley qualifies fifth. He’s just over two seconds behind the BMW of pole-sitter Jordan Szoke, who’s won the first two races of the season. “Second row is OK,” Daley says, “but I’m not happy with that gap to the front.” Reigning series champion Jodi Christie sits second on his Honda, while Kenny Reidmann’s Kawasaki completes the front row.

Though Christie leads early, Saturday’s race becomes a romp for Szoke, who finishes more than 10 seconds clear of Christie and 15 ahead of Reidmann. Farther back, Daley comes close to Michael Leon, but cannot challenge him for fourth. As Daley slithers from his leathers — gingerly, lest he foul his hands — he tells Weaver the Suzuki’s engine is sputtering at high revs and the rear tire is pumping on corner exit.

Back at the hotel, they pore over telemetry readings on Weaver’s laptop. The data is incomprehensible to me — where I see a flunked polygraph test, they see opportunities to pick up tenths of a second. Their conversation resumes in the morning, Daley still stretched out in bed, his arms gesticulating wildly, Weaver seated behind like a psychiatrist of speed. The sputtering is the result of a faulty fuel sensor, which is swapped out Sunday morning. To combat the tire pumping — the rear tire loading and unloading unevenly — they drop the swingarm pivot two millimetres.

Sunday’s race echoes Saturday’s. Christie again surges to an early race lead but this time he crashes. After inheriting the lead, Szoke pulls a gap and beats Reidmann to the line by a shade under seven seconds. Daley, free of mechanical gremlins, runs a smooth, consistent race, and finishes third, 10 seconds adrift of Reidmann.

The third place in Edmonton is Daley’s best finish of the season, though not his best ride. That Daley reserves for Mosport, where, in the first race of the weekend, he finishes fourth behind Szoke, Reidmann, and Christie. Nothing new there, except that this time at the finish Daley is just a second off the winner’s time. At the track that requires the most nerve and the most horsepower, Daley is suddenly a contender. But the next day bad luck returns. While reeling in the leaders he crashes. Then he gets back up and crashes again when the engine blows. Remarkably, it’s his only DNF of the season. His ranking at season’s end is fifth. “I’ll be back next year, and better,” he says.

While Daley collects his winnings from Edmonton ($2,100 for the weekend, which seems like a lot until you consider his costs — travel, entrance fees, tires, his tuner, and more), I chat with CSBK officials. “Trevor did well this weekend,” one staffer says, “didn’t do anything crazy.” I ask what constitutes crazy. “Sometimes he’s too aggressive, crashes too much.”

There is some validity to that — there’s no denying his aggressiveness — but even so, I sense a double standard. At the time of the Edmonton event, including practice, qualifying, and the races themselves, Daley had crashed four times. Meanwhile, Christie had gone down five times. Daley is dubbed the Wild Man. Christie’s reputation remains squeaky clean. People expect Christie to be aggressive — he’s defending a title, after all — but shouldn’t Daley be just as hungry for points?

Maybe Daley has to push this hard. After spending a week with him, watching him prepare, practice, race and rest (if you can call it that), I doubt he knows how to ride — or live — any other way. Whether it’s racing or pulling an all-nighter to meet a deadline, his drive is immense. While a rheostat governs most people’s lives, Trevor Daley’s uses a switch. He’s on — and all in — or he’s off. He has one speed, or none.

It’s 6 p.m. on Sunday. After tearing down and packing up, we’re ready to start the long slog home. The truck isn’t. Daley turns the key but the engine won’t turn over. He tries again. The silence is ominous. “Don’t worry, I’ve got jumper cables,” he says. He smiles as it starts with the boost, but the scene smacks of foreboding — made more potent by an approaching thunderstorm. Daley sets the itinerary. “We head south, turn left at Calgary, and then drive 3,000 kilometres.” After a hellish day and a half — I feel ill when it’s done — we’re back at his shop with another trophy for the shelves. I ask if he needs help unloading the truck. “No thanks,” he says, “I’m going to leave that until tomorrow. I need a break from race stuff. Think I’ll do some work on that Harley instead,” he says, gesturing to a customer’s bike. One speed, or none.