Ducati’s Monsters have aged remarkably well. When the model appeared at the Cologne show in 1992 it was a sensation. Released as a 1993 model, it, along with the 916, gave Ducati a one-two that kept creditors at bay. But, as Ducati learned when it replaced the sensual 916 with the cubist 999, fiddling with models well received by the public can be dangerous. While the public can be receptive to some new designs, if you’re replacing a much-loved model then it’s doubly hard to get it right. Ducati’s fix for the 999 was the 1098, which looked back over the 999’s shoulder to the 916 for styling cues. You just knew that when Ducati revisited the Monster, the firm wouldn’t be as brazen as it had been with its flagship sport bike. Indeed Ducati admits that the new Monster—and if you look beyond annual styling and engine variation it’s the first significant revision since its inception—had to have the immediately recognizable profile of the original. It had to be new, but it couldn’t look too new.

The engine, which shares capacity with its 695 cc predecessor, received slightly larger valve diameters and camshafts running in bushings, a change from heavier and bulkier bearings. Additional fins on both the head and the cylinder improve cooling, and an additional Lambda sensor for the second cylinder better allows the computer to modulate fuel injection. The upshot of the revisions is a claimed 9 percent boost in power to 80 hp and an 11 percent boost in torque to 50.6 lb-ft. The power is a welcome addition, because previous generation small-bore Ducati 620 cc and 695 cc twins were just a little too slow to be fully entertaining.

But more important than just a little more power, Ducati admitted in a roundabout way that its entry-level machines have in the past been too dull. While it’s true that buyers are willing to accept lower cost components—indeed they’re a necessity in machines with sensitive price points—cheaper parts can add up to a cheap motorcycle. The small Monster has been the biggest-selling bike in Ducati’s most popular range. Sixty percent of purchasers are buying their first motorcycle, according to Ducati, so if they’re ever going to become dedicated to the brand then this is the time to hook them—but if the bike is bland, where is the motivation to continue on to more expensive models? And after a day in the saddle, I can say with surety that the 696 has more of what makes a Ducati appealing than any previous entry-level Monster or Multistrada.

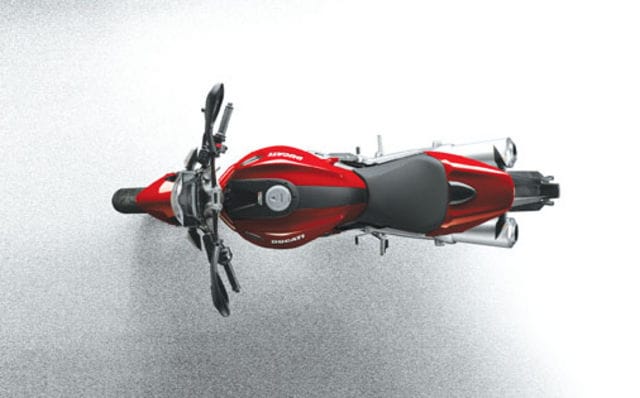

As soon as you thumb the starter button you’re struck by how the sound is improved. Air-cooled two-valve Ducati engines are among the best sounding motorcycle power plants, but you’d never know it by listening to many current models; instead of a low thump-thump they often produce an anaemic chuff-chuff. The 696, while not overly loud, has the classic Ducati beat. A Ducati staffer sees the skepticism in my face when I ask if the mufflers are stock and drags me underneath to show the homologation numbers stamped on the inside of the pipes. Aftermarket pipes are unnecessary but, alas, will likely be popular accessories. A first on a Monster, the exhaust pipes do not wrap beneath the engine but rather snake through the frame rails and exit to mid-height mufflers. The system is well designed and heat is safely kept away from the rider’s leg. Ducati claims that they wanted to visually simplify the profile of the engine, but backyard mechanics will notice the ease with which the oil filter can be accessed.

Long a Monster woe has been insufficient steering lock, an unforgivable gaffe on an urban bike. The first time I rode a Monster, at a press launch a few years ago, I nearly knocked down domino-style a row of bikes when I spun around to leave the parking lot—it had the turning radius of a school bus. Ducati’s cure on the 696 was to put functional air intakes into what looks like the fuel tank (15-litres of fuel is held deep down in the bowels of the bike; what looks like the tank is the 10-litre airbox). These screened-to-keep-critters-out intakes double as recesses to accommodate thumbs, and lock-to-lock movement is a claimed 64 degrees, which, frankly, means nothing to me; all I know is that you can do U-turns on narrow roads without resorting to three-point turns and embarrassing foot peddling.

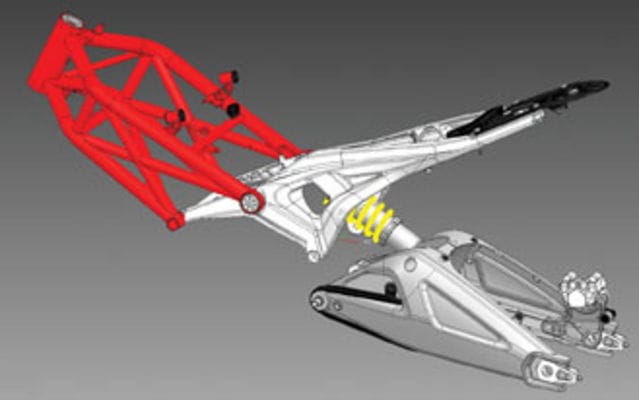

While the frame carefully mimics the Monsters of yore, closer inspection reveals that the steel trellis section ends at the rear cylinder head, from where a cast-aluminum subframe extends rearward and supports the seat. Tubing diameter of the steel main frame is larger, while unseen are thinner tube walls. The lighter subframe contributes to an overall weight reduction, and claimed dry weight is 161 kg/355 lb (168 kg/370 lb for the 695). Also unseen is the narrower midsection, essential since the 696 is favoured by beginners and women, and nothing aids confidence like two feet planted on the ground.

Amid the progress one traditional Ducati irritant remains—absurdly tall gearing. Top gear in the slick six-speed gearbox is only good at speeds over 120 km/h, and highway travelling is best in fifth or even fourth gear. It is more noticeable on this bike because the modest displacement of the 696 means that the engine needs to rev to make hay, as it lacks the bountiful midrange torque of the 1000 cc Ducati twins. But if it’s an inconvenience on the highway it’s a pain in the ass in the hills surrounding Barcelona, as Beppe, our guide, sets a ferocious pace, and I’m at a loss to choose a gear that suits. On tighter corners, second gear is too tall, but dropping down to first causes the engine to scream in complaint and the APTC clutch to slip in protest, as it’s intended to do. While the problem is irksome the cure is straightforward, and if I were to purchase a new Ducati I’d have my dealer lower overall gearing by either subtracting a tooth from the countershaft sprocket or by adding a few teeth to the wheel sprocket before I rode the machine from the showroom.

Stock settings on the non-adjustable 43 mm Showa fork seem a good compromise, but Spanish roads have never seen a winter like we’ve just had, so take my praise with a grain of (road) salt. The Sachs shock is adjustable for preload and rebound damping and is sufficient for the task. An area where Ducati admits that it has skimped in the past was on brakes for its less-expensive bikes. Interestingly, Ducati claims that brake feel is an area where small-displacement Monster owners were denied the true Ducati experience. To that end, the 696 has twin 320 mm discs and four-piston radial-mount calipers—impressive bits for a $9,495 motorcycle. More importantly, modulation will not terrify the novice, as actuation is smooth and lever effort levels are higher than those required for a comparable system on a pure sport bike. Keeping up with Beppe required frequent and frenetic use of the brakes, and although there was a slight increase in lever movement near the end of our sprint, there was no fade. The rear brake was not prone to locking—always a good thing—but it howled in use like the rear drums on my unloved, and now crushed, 1978 Buick.

Ducati has always made visceral motorcycles, but attention to detail has not always been its forte, seeming at times to have been burdened by the task. That seems to be changing. The 696 has a near-Japanese level of sophistication, exemplified by handlebar-mounted mirrors that pivot easily in stationary shells, like those on a car. Some find them fabulous, some find them useless; I find them somewhere in-between.

The dash, too, is nicely executed. I prefer the legibility of analogue gauges, but the bar graph tachometer is easy to read and all that’s missing is a fuel gauge (to replace the low-level warning light) and a gear position indication, which should be mandatory on motorcycles pitched to beginners.

Ducati staffers are among the most adept in motorcycling at deftly evading questions posed by those of us in the press. When I ask when the technology of the 696 will migrate to the rest of the Monster range they give me a look like they’ve never thought of the question before. Nor do they flinch when I tell them that it is highly unusual that the low-end bike in the range is the first to have the makeover. The answer, of course, is that you’ll decide the fate of this model and the rest of the Monster range. If it flies out of showrooms, other Monsters will mimic its style as quickly as fire swallows Southern California real estate, but if its reception is flat (and I don’t think it will be or deserves to be), we may just have the old Monster around for another 15 years.