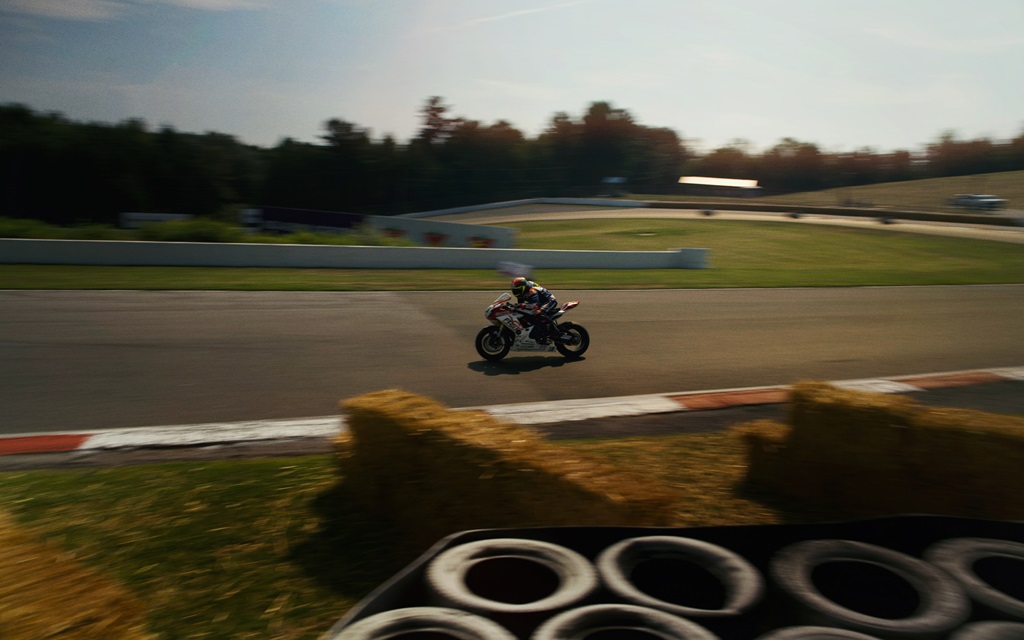

I’m absolutely fascinated by motorcycle crashes. Motorcycles transform from vehicles of immense grace to angry bulls in milliseconds, and pity the rider who finds himself catapulted to the heavens when a bike decides it would rather go bareback. A motorcyclist, like an equestrian or a boxer, is nakedly exposed to the forces of misfortune. I stood ringside at a boxing match and went home confounded. That such violence could be so beautiful was the alchemic fusing of opposites. Boxing is like ballet with dire consequences, and motorcycling is boxing of a different sort: the ramifications from a crash can be every bit as severe as a Sonny Liston shot to the head. Riding a motorcycle is hard, and, clearly, even the best riders benefit from a little help. But how much help do we need?

The most poetic riders are racers. A few years ago Honda circulated a video of its then MotoGP rider Casey Stoner rounding a corner. One corner only, shot with a high-speed camera that allowed the scene to be replayed in ultra slow motion. The bike ducked its head like a greyhound in stride but Stoner righted it and steered a course to safety, all the while applying opposite lock to compensate for the rear tire stepping out under power. At regular track speed the bike’s progress was incomprehensible — it wasn’t any easier to grasp the bike’s subtle movements than it would be to describe the characteristics of a bullet fired at your head.

Many motorcycles today — from MotoGP racers on down — rely on a mixture of human control tempered by traction control. Just because Stoner’s bike had traction control doesn’t mean that what he did is accessible to the great unwashed. Merely getting a machine with the capability of a MotoGP bike to the point where traction control adds a last little nudge forward is something only a handful of riders in the world can do. Maximum forward thrust on a racing bike happens beyond the point of lost traction, which is why Stoner was sliding — traction control helps him only by reducing the risk of crashing a sliding motorcycle.

Oddly, however, the first electronic rider aid — and still by far the most useful for you and me — has not gained acceptance on the racecourse: antilock brakes. On the face of it, it’s understandable: there are no surprises on a track — the corners are of known radii and the obstructions that we take for granted on the street (half-tons, stressed moms, oil slicks, gravel, deer, drunks) are nowhere to be found. At least that’s always been the reason supplied when I’ve asked why racing bikes are without ABS. But doesn’t arriving at a corner a little too quickly turn a known into an unknown? What if the rider in front of you zigs where he’s always zagged, or loses control and starts to crash? Conventional wisdom is that racers, through skill and preparedness, can outperform technology. I’m not so sure.

At the season opening MotoGP round former champion Jorge Lorenzo braked too hard and crashed. So did a bunch of other riders. It’s important to note that what traction control can’t do — stop a wheel from losing sideways traction while heeled over in a corner — was not a factor in nearly every crash. If run-of-the-mill ABS can stop me from exceeding the point where the tire loses traction, wouldn’t cost-no-object MotoGP-caliber ABS have allowed Lorenzo and his competitors to do the same? At this year’s Daytona 200 frontrunner Dane Westby downshifted twice instead of his intended once entering a corner and his rear tire skidded, pitched the bike sideways, then shot Westby off the top in a violent highside. Jason DiSalvo, who was running on Westby’s tail, seemed to have a moment of indecision (and perhaps even target fixation, though it’s important to acknowledge that reviewing video footage in slow motion is entirely different than reacting to an event in real time). As DiSalvo ran off the racing line the available traction diminished significantly, and he, too, highsided. (Neither rider was seriously hurt.)

Nearly every crash is caused by rider error. And DiSalvo paid for Westby’s miscue. But racing bikes (and indeed many street bikes, even beginners’ machines) have slipper clutches, which allow the rear wheel to spin unencumbered by engine braking, for just those moments when a rider downshifts too aggressively. So why did Westby’s wheel even begin to slide? Many riders prefer a small degree of drag from the rear wheel (the slipper clutches they use are adjustable), which allows them to forgo traditional rear wheel braking to concentrate on the all-important front brake. Had Westby decided to forgo preference for safety, his double-downshift would likely have resulted in no more than a few seconds of lost time while he regained momentum.

Two summers ago I left the office on a BMW F800GS and within a kilometre had activated the ABS three times. The first time it was because gravel on the road was blocked from my view by a city bus. The second time was because a car entered my lane. And the third time was because I was distracted by the effects of two close calls and didn’t notice until the last moment that the traffic light had turned red. Forgoing electronic aids has been, for some riders, a point of principle, but we’ve reached the point in the evolution of the motorcycle where a rider who crashes because he decided to forgo the option of ABS is the equivalent of the snowmobiler who plunges through ice: merely a footnote in the ongoing evolution of the species known as natural selection.