When Ivan Mavrinac started making leather suits for motorcycle racers, armour was something you attached to the side of a ship, not the shoulder of a jacket. But Mavrinac, who taught himself the arts of cutting, shaping, and stitching leather and in the process became a star of the small world of Canadian motorcycle fashion, noticed that his customers were sporting injuries after falling off bikes. It was the late 1970s, Mavrinac had just started making race leathers, and there was a group of people who, he knew, were better able to protect themselves against the assaults of their sport.

Hockey players, that is. Mavrinac got some hockey pads, cut them to fit, inserted them into leathers, and transformed the form-fitting leather suit of the day into a precursor of the modern protective motorcycle racing suit. Racers were impressed.

Mavrinac’s skill and a sort of manic work ethic brought success to the man who had quit a job at an auto parts factory in 1970 and started making leather belts in his mother’s basement. He was a natural, and even his earliest leather work was good enough to sell. It was the start of a lifelong pursuit, and Mavrinac would spend the next 35 years producing leather goods and clothing, evolving his craft, and impressing customers. When he died on March 29, 2012, the 63-year-old leather worker left unfinished business on his cutting table, and when his wife Jan and their daughter Jennifer held a memorial service at the IM Leathers store in Hamilton a few weeks later, the room filled with friends, admirers, and customers, several of them in clothing that he had made.

Outside the store on that Saturday were three bikes, a Yamaha FJ1200 with elaborate paint and a loud pipe, an MV Agusta F4 with a pretentious licence plate: “RZ500,” and an old Triumph Bonneville with a leading-shoe front brake. Inside, there were people who would have appreciated the Bonnie when it was new and who might have thought tagging an MV Agusta as a Yamaha two-stroke made sense. Just inside the door, Reverend Brother Walter Tucker watched the crowd from under a funky knit cap. He’s a gnome-like man with a bushy white beard, a rap sheet for dealing pot, and nearly 80 years behind him. He still rides an 1100 cc Honda and he wore a replica Dave Aldana jacket, complete with wild design work. Mavrinac did not make the jacket, but made it convertible, with zip-off sleeves. Rev. Bro. Tucker says he was a genius. “Whatever you could imagine, he could make.”

The Bonneville’s owner was a Toronto author and former musician, Lee Gotham, who showed up with a six-pack of Heineken. He wore a black leather jacket with a Union Jack on the right shoulder and a French tricolore on the left. Mavrinac made the jacket in 1979, and it still fit Gotham, though just barely. When Gotham worked as a musician, he didn’t make a lot of money, but he had style: Mavrinac made pants with zippered lower legs for him, so he could wear them tight around the ankles on his bike, then upzip the bottoms and turn the pants into two-tone flares for stage work.

There were others who arrived at the memorial with beer, which was a fairly common practice when people showed up to watch Mavrinac work. Customers would sit and drink while Mavrinac worked at his sewing machine, mesmerizing with the speed of his movements, talking about politics, art, religion, or philosophy while freshly stitched leather pieces flew out of his machine. Around him would be the squeezings of other projects, bits of leather left in heaps on the floor, to be cleaned up by someone else or to grow dusty, it mattered little to him which.

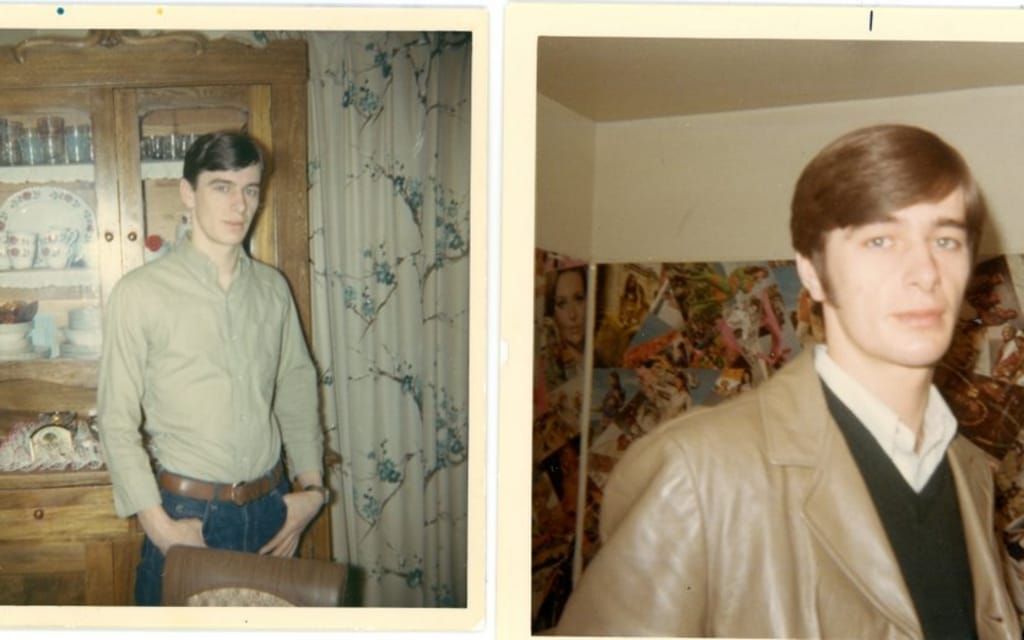

Ivan Mavrinac was born in Croatia in 1949 and left there a year later with his family, landing first in Italy, and five years after that, in Canada. Driven out of Kirkland Lake by blackflies and a barren landscape, the Mavrinacs settled in Hamilton, Ontario, where there was family. Ivan’s father took work as a machinist and his mother hired on at an auto parts factory — the same one Ivan would later abandon in order to set up shop as IM Leathers in her basement.

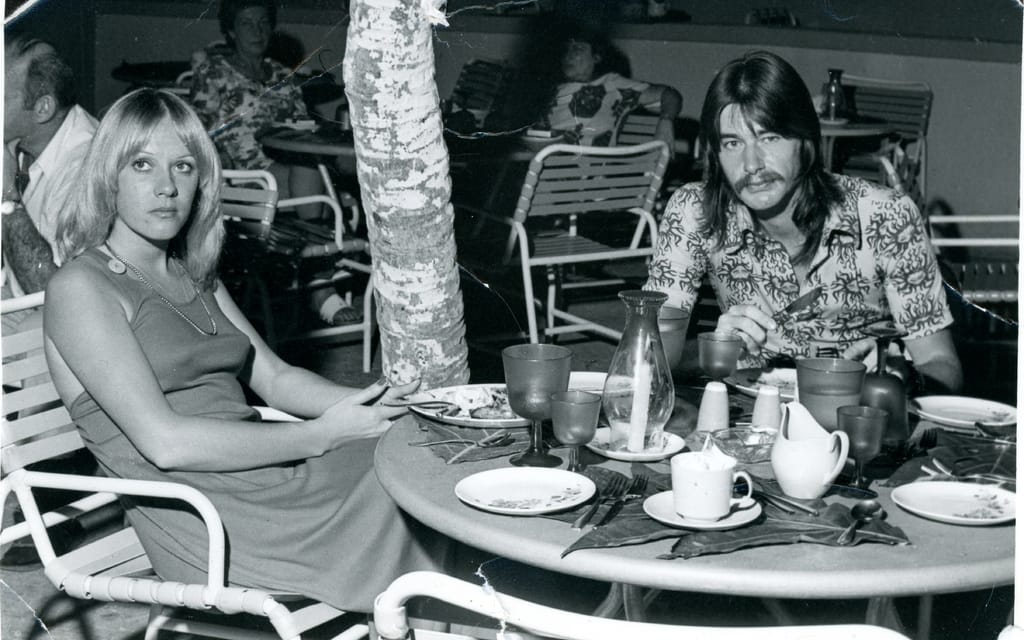

Before that happened, he met the beauty who would become his partner for life, Jan Simpson. It was at a dance in 1967, they were both 18 years old, and in two years they would be married. When Ivan began selling his boutique belts, Jan drove to Montreal with a sample case of them and convinced stores to take them. She wore a leather miniskirt that Ivan had made for her, but the advantage was already hers, there in the sample case.

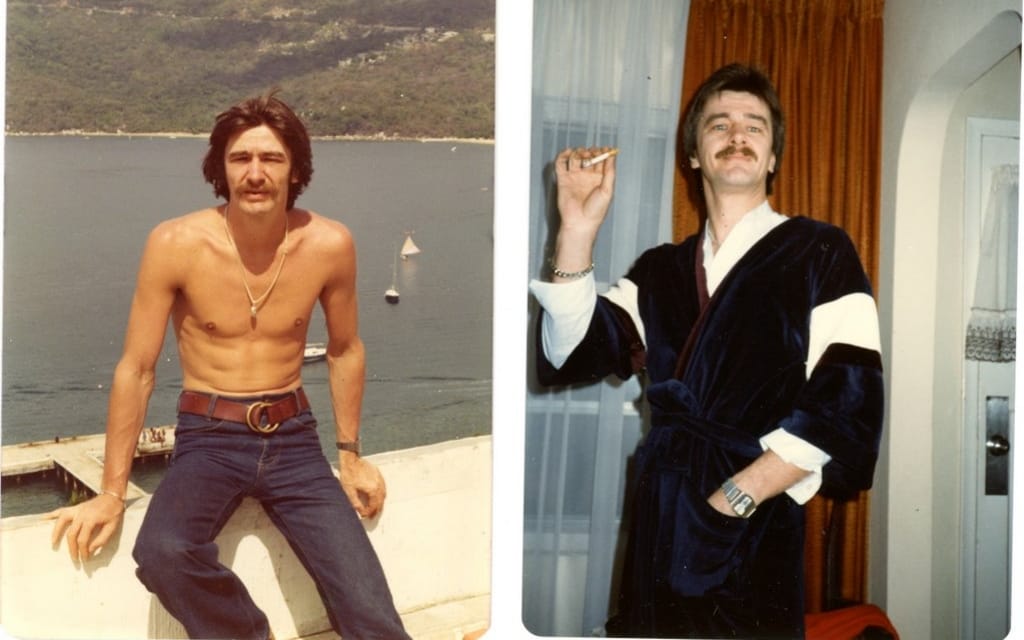

Mavrinac expanded his product line, began making wide belts for weight-lifters. He sold them to York Barbells and other makers of gym equipment, and Jan says business was as good as it ever got. By about 1975 they had a factory and a pair of studio spaces on Locke Street in Hamilton.

They also had a daughter, Jennifer, who remembers her father’s habit of tearing things apart in a sort of helter-skelter mania. He would fearlessly rip into something that wasn’t quite right, often with no sensible plan for putting it back together. He tore the front wall off a house she owned once; another time he pulled apart the engine of the family car, then sold it to a mechanic rather than try to reassemble it. “My father always looked shocked when he tore things apart and they blew up,” Jennifer remembers.

In the mid-1970s, business was good enough for IM Leather Goods and the Mavrinac family to move into a two-story brick house just off the main street of Hamilton. There were several motorcycle dealerships in Hamilton and even half a dozen chopper shops, and motorcyclists discovered this quirky, driven leather worker. He began making street leathers, chaps and vests, and local shops referred customers to him. He could make a suit fit no matter how disproportioned the rider might be.

Despite his growing reputation as a maker of good motorcycle gear, he never learned to ride. In fact, he never even drove a car, which might help to explain his reluctance to get the family Lincoln running again after he demolished its engine.

Maybe not for him to ride, but there were frequently motorcycles parked outside his house as he worked his leather trade, and some of those bikes would have been equipped with sirens. The Ontario Provincial Police and the Hamilton-Wentworth police forces were unable to find riding jackets at the time that would serve the needs of motorcycle cops. They came to Mavrinac, who accepted the challenge of creating, making, and then servicing police jackets. Alongside the full deckers of motor cops, there were sometimes the choppers of one-percenters. The IM shop became a sort of demilitarized zone, frequented by cops and bikers who would sit on opposite sides of the store, ignoring each other, while Mavrinac repaired the jacket of an outlaw club member who kept a careful eye on his jacket and club patch.

Mavrinac’s move into racing leathers started with John Parker, a former Number 1 plate-holder in dirt track racing. Along with Jordan Szoke, Steve Beattie, and others who made their names on race tracks here and in the States, Parker was at the memorial. He still races, though he’s old enough to know better. In 1977, when he was 17, he brought a set of leathers to Mavrinac for some work, and they became the pattern for his first set of IM race leathers. Two years later, making and fixing race leathers had become his main occupation, and his ability to cut and shape to a particular need served him well. If a racer brought in a damaged suit and limped from a bruised hip, Mavrinac would build padding into the gear. If it was too restrictive, he would find ways to improve its flexibility. As time went by, motorcycle race gear evolved and Mavrinac was in the centre of that process, not driving it, but engaged in it. He built suits for dirt trackers, road racers, and even snowmobile racers. At the time of his death, he was working on a suit for a racer named John Kehoe. It incorporated Kevlar and stretch panels and would have been a good suit. It probably would have lasted for years.

Early this year, IM Leather Goods moved to a new store on King Street in Hamilton. The store is divided into two distinct areas: a front retail area and a rear work area. Five sewing machines line the wall on the left side and on the right there is a large cutting table and a rack of garments waiting for attention. There was a variety of leathers there on this Saturday in April: a road race suit with the right arm missing, a soft leather jacket for casual wear, a dirt track suit with the ass scrubbed out of it. At the front of the work area was a hook with set of race leathers on a hanger. A note on the hanger spelled out some instructions for repairs. Let the jacket out an inch on each side, let the waist of the pants out an inch on each side and replace the Velcro closure on the collar. The suit was old, but not done; back in for repairs and updating.

Over the course of his career, Mavrinac made many kinds of leather garments for many kinds of people, including musicians. Long John Baldry and the band members of Crowbar wore his leather clothing on stage. Hamilton’s Teenage Head bought his gear, and producer, musician, and motorcycle rider Daniel Lanois bought a number of his pieces. Lanois once had a girlfriend who knew John Parker, and it came to pass that he met and became an admirer of Mavrinac; he still wears a motorcycle jacket with a sheepskin lining that Mavrinac made for him. “He was a master tailor,” Lanois said in a telephone conversation. “He was gifted.”

Gifted, certainly, but organized? Not so much. Racers coming in for a trial fitting might find that the leather hadn’t even been made ready. “Just wait there. It’ll only take two minutes,” Mavrinac would say. Customers were invited to have a beer while they waited, and sometimes a racer would leave a van at the curb, packed for Daytona, while inside Mavrinac finished a set of leathers to be used in the races.

In February, Mavrinac suffered a heart attack that laid him low. A hand-written sign appeared on the shop door at King Street, and word spread through the legions of his friends and customers. For five weeks he remained in a hospital, getting worse, and finally his family came to an unhappy and unavoidable truth. Jennifer, who was with him, talked about it without a hitch in her voice. “He was headed somewhere. He’s got shit to do.”

Jennifer, the grown woman who will continue her father’s work and will keep the King Street store open, remembers better days, when she would take naps in the piles of lining material by her father’s work table. She grew up with his talents, had a clothing line a few years ago and made boutique leather fashions. Once, she and a friend charged into the workshop on a Hallowe’en night, and there she whipped up a pair of leather corsets for their costumes, working skillfully and quickly, amazing her friend and establishing that the apple, indeed, doesn’t fall far.