Suzuki’s Bandit 1250S is a bike that wears many hats. It’s a sport bike, a -touring bike and a commuter all in one. We tested it for a season, but to our dismay, we eventually had to return it.

It’s a company perk to be able to get long-term test bikes. Motorcycle journalists, as somewhat egocentric individuals, can easily request exotic, unobtainable machines and indulge in pleasures simple folk must sacrifice years of salary to enjoy.

In reality, we’re ordinary hacks, with aging, battered bodies. Contortionists we’re not, and to get the most out of a long-termer, it must be ridden, and ridden often. So it’s more sensible to choose a machine that will invite us to ride it. Suzuki’s Bandit 1250S fit our staff like a glove.

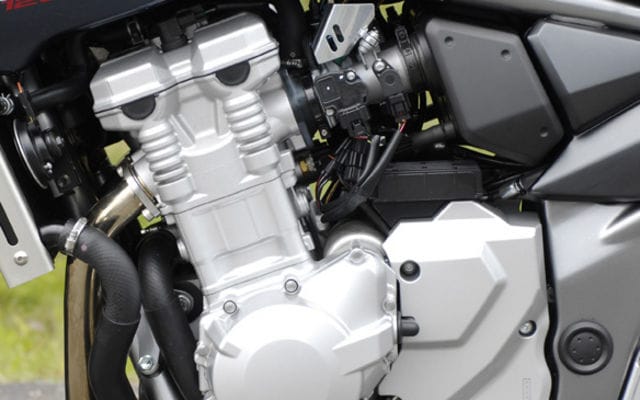

The design philosophy behind the Bandit places function over form, in an affordable, well-performing package. The Bandit is characterized by its steel-tube cradle frame, a conventional fork, tubular handlebar, upright riding position, conservative styling and steering geometry, and until recently, an air-cooled inline four with ancestry tracing back to the original GSX-R of the mid-1980s.

To improve performance while meeting stringent emissions standards dictated a complete makeover for the big-bore Bandit for 2007. Replacing its former carbureted 1,157 cc air-cooled engine is an all-new liquid-cooled, fuel-injected and counterbalanced powerplant designed specifically for the Bandit 1250S.

Suzuki engineers began by increasing stroke by 5 mm to 64 mm, while retaining a 79 mm bore, thus bumping displacement to 1,255 cc. Liquid-cooling allows cylinder bores to be placed closer together, for more compact external dimensions (the cylinder head is 20 mm narrower). The narrower design also enabled a new smaller and lighter alternator to be relocated to the left end of the crankshaft, reducing mechanical losses.

The new cylinder head sets valves at a narrow, 16-degree angle with a reshaped squish band for improved combustion chamber efficiency. Smaller diameter valve stems (4.5 mm) improve airflow, as do redesigned ports. The compression ratio is up a full point to 10.5:1, though the Bandit retains the ability to run on cheaper, regular fuel. Transmission shafts are now stacked vertically to reduce engine length and the gearbox has gained a cog, now a six speed.

Our test bike was initially stiff shifting, but a quick adjustment of the linkage made an immediate improvement, and it got progressively better as the kilometres accumulated, with only an occasional reluctance to downshift smoothly. It was more of a mild annoyance than a problem.

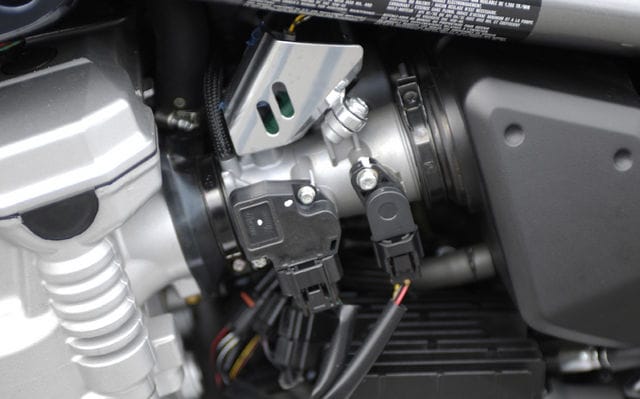

The Bandit’s EFI is a closed-loop system (with an exhaust mounted oxygen sensor) and uses 36 mm throttle bodies with two butterfly valves, one controlled by the rider via the twist grip, and a secondary valve controlled by the ECU. Idle control is automatic, improving cold starting and reducing emissions. Spent gases are expelled via a catalytic-converter equipped 4-into-1 exhaust, which incorporates Suzuki’s PAIR (Pulsed-AIR) system to further reduce emissions by injecting air into the exhaust, thus reducing the amount of unburned gases. This latest Bandit meets tough Euro 3 and Tier 2 emissions standards.

Engine output might not be typical of a modern large-displacement inline four at 98 hp/7,500 rpm, but this engine is about torque, lots of it and at low rpm. The Bandit 1250S claims a peak of 79.6 lb-ft at just 3,750 rpm, up substantially from the previous model’s 67.6 lb-ft at 6,500 rpm.

The engine fires up instantly without having to fuss with a choke or fast-idle lever, and immediately noticeable is an engine that is mechanically quieter than the previous air-cooled mill, thanks to the noise damping qualities of liquid cooling. The engine responds to throttle input without hesitation, regardless of engine temperature—albeit without the frenetic urgency of a snappy supersport—allowing you to ride away almost immediately without the cold-blooded surging characteristic of carbureted machines.

The hydraulically actuated clutch requires a light pull and engages smoothly and progressively. Once warm the engine maintains a smooth and relaxed demeanour throughout its rev range, even when lugged down to 1,500 rpm in top gear. It offers up ample torque and real-world power, making shifting optional and allowing you to jet past traffic in top gear with a simple twist of the wrist.

The meat of its powerband is in the useful 90 to 130 km/h range and the deceptive manner in which the Bandit builds speed can get you in trouble with the law. Enthusiastic application of the throttle should immediately be followed by a glance at the digital speedometer.

Vibration is mild and unobtrusive, further reduced by a rubber-mounted handlebar and weighed-down footpegs. Throttle effort is light, and response is direct and easy to modulate. One of our testers reported a very slight surge in acceleration when shifting gears, noting that it felt as though the secondary throttles opened, and then closed slightly before stabilising. While perceptible to those with acute senses, the effect was so subtle that it can hardly be considered problematic.

The compact engine gave engineers some latitude when developing a new chassis. The engine’s shorter front-to-rear dimensions allowed the use of a longer swingarm, creating a more stable chassis, while its narrower profile made it possible to reduce the width of the seat-to-tank junction area (albeit at a reduction of 1 litre in fuel capacity), improving rider comfort while making it easier to reach the ground at a stop.

The riding position is upright and spacious, relieving wrists and spine from unnecessary trauma. The tubular handlebar is reasonably comfortable, though it places wrists at an odd angle. Some riders felt it needed less pullback and could have been wider, while others found it just right. About $30 and a half-hour of work will easily appease any rider, a benefit of the simple design. The seat is flat, firm, and free of intrusive sharp edges, serving well for medium-length rides. Seat height is two-position adjustable, from 790 to 810 mm (31.1 to 31.9 in.), though it takes about 10 minutes and a few of the supplied tools to make the change. One of the taller testers on staff raised it for increased legroom and it remained that way throughout the season, none of the shorter riders seeming to mind the added height.

Passenger accommodations are good thanks to the wide and flat pillion, vibration-damped footpegs, upright position, and an easy-to-reach grab handle. The passenger’s forward view is good thanks to the stepped seat design, particularly if the rider’s portion is set to the low position.

Engine heat is well managed with no undue warming of the thighs or feet. Wind protection on the semi-faired 1250S is adequate, the fairing shielding the torso while deflecting the windblast to helmet level, increasing wind noise somewhat. A taller windscreen would reduce wind noise, but adds the risk of wind buffeting, something that is absent on the Bandit.

The traditional double-cradle steel frame was beefed up with larger diameter downtubes, increasing torsional rigidity by 10 per cent. Rake, trail and wheelbase remain unchanged at 25.3 degrees, 104 mm, and 1,480 mm (58.3 in.). The Bandit 1250S gained 10 kg over the previous model, now at 225 kg (496 lb; 229 kg/505 lb for the ABS model).

It handles a variety of riding conditions very well. Shod with the stock Dunlop D218 tires, it exhibits a slight reluctance to maintain a lean in corners, requiring a light, yet steady push on the handlebar to maintain its line. At 5,500 km, we installed a set of Dunlop Qualifiers and handling improved, becoming more neutral.

As a cost-cutting measure, economical suspension components are used. A conventional 43 mm telescopic fork is preload adjustable and the single shock is adjustable for preload and rebound damping. Suspension compliance, though not overly refined, is firm without being harsh, and proves to be a reasonable compromise between comfort and control. The Bandit’s suspension is overwhelmed when riding aggressively, however; under-damped for the higher loads exerted upon it by higher speeds on winding roads, mostly noticeable when negotiating fast sweepers, where it weaves ever so slightly. The bike can comfortably maintain a quick pace, but serious track-day riders would be better off with a sportier machine. When ridden at a more sedate pace, stability is excellent, the big Bandit remaining oblivious to crosswinds.

The brakes work well and provide adequate power with moderate effort while being easy to modulate. While we would have preferred the ABS version, it was unavailable for long-term testing. For 2008, the Bandit 1250S is available solely with ABS at the same price of the non-ABS 2007 model at $10,799.

Fuel consumption is reasonable at 5.9 L/ 100 km (48 mpg) in combined highway and city riding, giving the Bandit a range of 320 km from its 19-litre fuel tank; sufficient to make it a worthy sport-touring mount, and it can easily handle the added load of a passenger and touring gear, the engine having loads of reserve power.

Daily life with the Bandit proved to be engaging. Its fairing-mounted mirrors provide a good rear view, remaining relatively clear at most speeds. Its twin headlights provide decent illumination for night riding, with both beams projecting a broad swath of light. Underseat storage capacity is a bit lacking, but will accommodate a disc lock or other small items.

The instruments, comprising of an analogue tachometer and digital speedometer, as well as the usual array of warning lights, fuel gauge, dual trip meters and clock, are well positioned and easy to read. A steel fuel tank allows mounting of a magnetic tank bag; a definite advantage for someone contemplating a road trip, and a standard centrestand makes maintenance a snap. The only maintenance our bike required was an oil change, which cost $40 and took about 15 minutes to perform.

In an office garage sometimes occupied by more striking and higher performance machines, including at one time a Benelli TNT and a Ducati 1098, it would have been easy to overlook the Bandit. But alluring exotics can only provide a short-term thrill. Like comfort food or a sturdy shoulder to lean on, the Bandit was there, faithful and forgiving, ready to give when asked. It provided a convenient perch for a quick run to the convenience store, and a comfortable, capable platform for weekend jaunts in the country or longer rides out of the country.

We’re glad Suzuki has one in its 2008 line-up, and it added the $11,999 Bandit 1250SEA, equipped with fairing lowers, taller windscreen and hard saddlebags, as well as standard ABS. This is the next logical step in Bandit evolution, making it much more versatile than the standard model for a very reasonable price increase. We were sad to see the Bandit go, but now we have two models to choose from.

From the Saddle:

I was predisposed to liking the Bandit 1250S. While its styling is not worthy of a headlining spot at the Guggenheim’s The Art of the Motorcycle exhibit, I favoured its unassuming lines and placid appearance. What really captured my attention, though, was its new engine and its promise to deliver bountiful bottom end performance and arm tugging roll-ons. Riding the Bandit had me immediately at ease, with its relaxed demeanour, comfortable ergonomics, and all-around goodness. The engine was smooth and quiet, the handling stable and predictable. Oh, and about those roll-ons, my arms are just now shrinking back to their original length and my silly grin is finally fading, much to my girlfriend’s relief.

—Michel Garneau

Purposeful. That’s the word that best describes the Bandit 1250S. It’s almost in a class by itself; not quite naked bike, sport bike or sport tourer, it performs well enough in each respective category that it probably best emulates the long gone UJM. Handling isn’t as sporty and it’s not as powerful as Yamaha’s FZ1, but its engine is much more manageable and it costs less, even the dressed up SEA version. It also costs thousands less than the BMW R1200R and Honda VF800, is as versatile and for 2008, has standard ABS like both those bikes. We’ve yet to test Honda’s new (and not yet priced) CBF1000, so it might match the Bandit’s dollar for performance value, but even so, the Bandit proved that good performance doesn’t always have to mean high performance.

—Costa Mouzouris

Photos: Hugh McLean