Standing around with other journalists after the day’s ride in the mountains near Malaga, Spain, I comment on what I believe is the new Ducati Diavel’s most successful styling element: its clean tail section with vertical lights that run underneath the passenger pad. “Oh, you must be joking,” said a testy American standing alongside, “it’s a great looking bike except for the hideous tail end.” And on it went. Everybody had an opinion and no one agreed on anything, except for this: if you set aside its looks and talk about its function, what Ducati has done with the Diavel is astonishing.

Here’s why: to design a bike around a 240 mm rear tire is to drape a millstone around an engineer’s neck. No bike requires a tire this size. MotoGP bikes have smaller tires and have 100 horsepower more. The reason that bikes have tires like this is for purely aesthetic reasons, and the role of the men and women who design the motorcycle is to mitigate the disastrous effect that a tire this fat has on handling.

Rear tires this large make a motorcycle handle like a corpse has been loosely strapped to the pillion pad. It makes the machine reluctant to turn, and then, when it does turn, it imparts the confidence of an office chair tilted onto its rear legs. It is not a comfortable sensation.

But Ducati, working with Pirelli, came up with a new tire that fits on a 17-inch rim (all other 240-section tires are 18-inch) and the inch less of rim diameter forces the rubber to have more curvature in its surface. At least that’s what they told us—and they seem to be telling the truth. Snaking up a mountain road, our speed is no less than what I would ride on a naked or a sportbike. The Diavel changes direction easily and imparts confidence. The only downside to the fat tire is that it doesn’t transmit quite the degree of feel that a sportbike-standard 190 mm tire would give. But compared to other fat-tired bikes the Diavel is in a class of one.

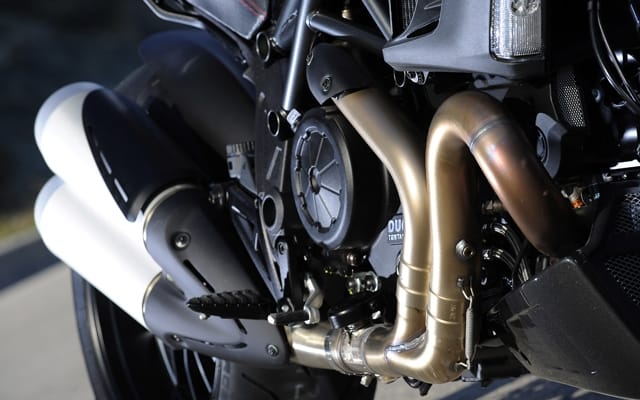

Power is the from the same 1,198 cc mill that powers the Multistrada 1200. Revisions to the exhaust system boost power to 162 claimed at the crankshaft, 12 more than the Multistrada claims. It’s a stonking engine, and likely gives around 145 horsepower at the rear wheel. Other deviations from the cruiser norm include plenty of ground clearance for the footpegs (forward pegs, mercifully, are not an option—only tobogganing should be done with the feet a metre ahead of the torso).

Clever design touches include a retractable passenger grab rail that extends out just above the taillights and passenger footpegs that fold neatly against the bodywork. This should be required fitment for sportbikes, where rarely (if ever) used passenger pegs foul the lines. As befitting a Ducati, the brakes are by Brembo, and are progressive and very strong. To make room to allow the seat to drop down to the 30-inch range, engineers relocated the shock for the swingarm below the engine and moved the battery to the bellypan ahead of the engine.

Often enthusiasts as they age pine for the handling of their old sportbikes but fancy something that is gentler on the body and that can tolerate a more sedate pace (they write us all the time seeking advice). Well, this is your bike. Its styling may be divisive (I like it from certain angles more than others, to be sure) but when it comes to function, this is a righteously successful motorcycle.

The Diavel comes in red or black at a suggested retail price of $18,995, while the Diavel Carbon adds carbon fibre trim and Marchesini forged wheels for a $2,000 premium.