The murder of the Donnelly family is a tale so depraved that it could have happened in the gothic South of William Faulkner rather than the pastoral farmland of southwestern Ontario. Paul Bremner rode out and picked up the story.

The group of men walked in silence, the snow crunching softly beneath their boots. The night was bitterly cold, but whisky had numbed their senses and fired their sense of purpose. As they approached the log cabin they tightened their grips on the weapons they carried: axe handles, spades, and pitchforks. The leader of the group motioned for the men to remain where they were. He tested the cabin door, and then quickly slipped inside.

The sound of locking manacles woke big Tom Donnelly. He opened his eyes to see the face of Jim Carroll, the hated local constable. Realizing his hands were bound, Tom cursed. “What is it this time? What’s the charge?”

Carroll ignored Tom and roused the rest of the family: James Donnelly Sr., his wife Johannah and their young niece, Bridget, recently arrived from Ireland. Young Johnny O’Connor, a visitor from next door, remained in bed unseen. As the family gathered in the kitchen, James Sr. demanded an explanation for the intrusion. Suddenly, Carroll let out a whoop. The doors burst open and men filled the cabin, their faces smeared with soot, clubs raised for killing blows.

Some 130 years later, my wife and I ride west under a baking sun into the heartland of Southern Ontario’s farm country. The land is flat, the road straight, and the wind hairdryer-hot. From time to time, our noses wrinkle with the pungent smell of superheated manure. I nudge into a higher gear for a low-rpm lope as we roll by endless cornfields and through the main streets of quaint small towns: Tavistock, Fairview, Elginfield, and, finally, Lucan.

The stately yellow-brick homes and bucolic farm fields make an unlikely setting for a massacre. Yet Biddulph Township, as it was then known, was once the scene of a crime so shocking that it inspired books, movies, television shows and even a Stompin’ Tom Connors song: The Murder of the Black Donnellys.

The bare facts are these: On February 4, 1880, four members of the Donnelly family were beaten and stabbed to death by an armed mob, and their log home burned to the ground. The killers then marched to a neighbouring property and shot a fifth Donnelly to death in the doorway of his brother’s house. The perpetrators weren’t a gang of outlaws. Chillingly, it was a group of fellow citizens: the Donnellys’ neighbours did them in.

We’ve ridden to Biddulph to learn the story of the massacre and the bitter feud behind it. And, of course, to hear a few good ghost stories. Because legend says that the spirits of the Donnellys haunt their former homestead and the road that runs by it, the Roman Line. We’re turning onto that road now. Even in midafternoon the Roman Line is eerily empty. There are no farmers at work in the enormous corn and soybean fields and virtually no traffic; we pass only a single car as we ride the eight kilometres of hardpacked gravel that leads to the Donnelly homestead.

The current owner is waiting for us at the driveway. J. Robert Salts is a heavyset man, talkative, with a mischievous sense of humour. He purchased the Donnelly property (then listed as a property with “an interesting background”) in 1988. Since then he has become one of the chief guardians of the Donnelly story and has written a book about his family’s life on the property. As we sit in the shade of a horse chestnut tree behind the homestead, he tells us his version of the story.

According to Salts, the seeds of the feud were sown when James Donnelly Sr. fell into a property dispute with a man named Patrick Farrell. On June 25, 1857, James Sr. attended a community “logging bee,” to help clear trees from a neighbouring farm. Farrell was there, and the two came to blows. The fight ended when Donnelly cracked Farrell on the head with a handspike (a large wooden lever), killing him instantly.

James Donnelly went into hiding for almost a year, living in the woods bordering his property and sneaking back to the farm for food and supplies. He even managed to pitch in with the chores, wearing his wife’s clothes as a disguise. Finally, living rough began to take a toll on his health. He turned himself in and was sentenced to hang.

Thanks to frantic petitioning by his wife—and a government which had no urge to upset Catholic voters in an election year—James Donnelly’s sentence was commuted to hard labour. Seven years later, alive but in broken health, he returned to Biddulph.

By that time the Donnellys’ relationship with their neighbours was also broken. Allies of the Farrell family, outraged over James Sr.’s lenient sentence, blamed the Donnellys for every unsolved crime in the area. Barn burnings, thefts, even a series of bizarre animal mutilations—all the work of the Donnellys, they insisted.

Salts noted that jealousy also plagued the Donnellys. They were a proud, handsome family, and, despite their legal problems, shrewd businesspeople. Over the years they had prospered, moving from farming into the lucrative stagecoach business. Only out for themselves, people whispered.

By January 1880, the tension had reached the boiling point. When someone burned a local barn, James Sr. and Johannah—then in their 60s—were immediately arrested by members of the Biddulph Peace Society, a local neighbourhood watch that had the Donnellys firmly in their sights. Three justices of the peace, who heard the case, knew a frameup when they saw one, and declared there was no evidence to charge the elderly couple. Furthermore, if the Peace Society could not come up with proof, its members would be ordered to pay damages to the Donnellys. For members of the Peace Society’s secret “vigilance committee,” it was the last straw. On February 4th they made their move.

James Sr. was the first to fall, his skull cracked open. With a roar, Tom burst through the crowd of attackers and launched himself through the front door. More men were outside, waiting, and they set upon Tom with pitchforks and clubs.

Johannah, begging for time to pray, was beaten down on the kitchen floor. Bridget fled upstairs, but found no escape from the mob.

Before leaving, the men poured lamp oil on the beds and set them on fi re. Johnny O’Connor, hiding under his now fl aming bed, waited until the last men left, then escaped to a neighbour’s house. As he ran through the inferno, he inadvertently stepped on Johannah’s lifeless body. To his horror, he heard the old woman let out a low groan.

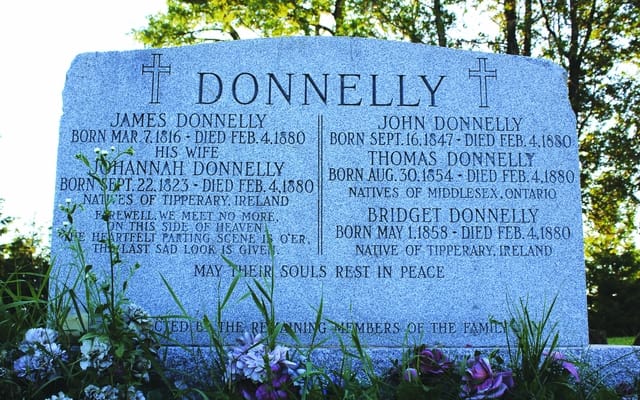

James, Johannah, Bridget, and Tom were buried in one coffin. The fire had left no more than ashes and fragments of bone. John Donnelly, shot later the same night in the doorway of his brother Will’s home, was buried in his own casket. No one knows how many people were in the mob that night. Historians believe at least 30 men were involved. Ultimately, 13 were arrested for the Donnelly murders, and six charged. Despite damning testimony from Will Donnelly, all were found not guilty.

The trial caused a media sensation. When the verdict was announced, the defendants were carried out of the London, Ontario, courthouse on the shoulders of their friends. A spontaneous parade began in the direction of the bar at the City Arms Hotel, with 1,000 people joining the accused for their walk of triumph. But not everyone was in a mood to celebrate. Later that night, Bob, one of three surviving Donnelly sons, strode through the crowd of revellers and up to the bar and announced, “I want all of you murderers to come and have something.” No one took him up on the offer.

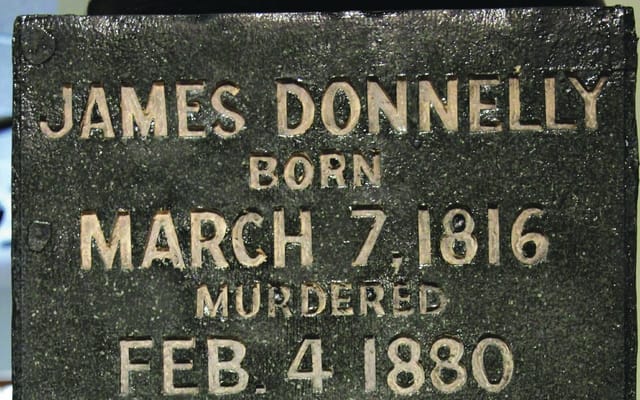

Will, Bob, and Pat Donnelly built a new homestead on the family property, and planted five horse chestnut trees—one for each Donnelly who perished that night. Two remain standing today. Following the funeral, Bob erected a single tombstone for his slain kinfolk—a tall black marble spire, with the word “murdered” carved beside each person’s name. In 1964, the local parish priest, tired of the attention the stone was receiving, replaced it with a more modest gravestone. Yet even this simple stone hints at a chilling tale: fi ve members of a single family, dead on a single night.

More than a century later, the Donnellys are not forgotten. The Town of Lucan has opened a museum to commemorate the incident, although some of the older people in the community still avoid the subject. Descendants of the vigilantes still live in the area, and no one wants to be reminded that their great-greatgranddad murdered his neighbour on a cold winter’s night. And, of course, the ghosts remain. Salts says that visitors to the property have experienced odd things: faces in the window of the homestead, or a touch on the shoulder when no one’s there. Psychics have reported seeing the ghostly fi gures of a bearded man and a stern-looking woman, dressed in homespun clothes.

Salts says the strongest ghostly experiences seem to occur in the barn, likely because its timbers date back to the time of the massacre. A pair of documentary filmmakers who spent a night in the barn said they heard footsteps in the straw and felt a strange pressure in their chests. In another incident, a teenaged girl said something tried to grab her. “When we looked at her arm, we saw she had fresh bruises in the shape of a hand—she got very upset,” said Salts.

Perhaps the most famous stories involve the Roman Line. Legend has it that horses refuse to travel the Roman Line on the anniversary of the murder, and avoid the Donnelly property at all times—riders have had to walk the skittish animals past the property. According to Salts, the previous owner of the homestead tried to board a horse, but the frantic animal bolted at every opportunity.

I was hoping to add to that list of supernatural encounters, but no spectre emerged during our time in Biddulph and no ghosts crossed our path. Until early evening, that is, when we parked the bike to take photos of the old schoolhouse where the so-called Peace Society plotted their bloody murder.

A man on a silver Honda Superhawk pulled up, worried our motorcycle had broken down. His name—Rob Donnelly. Rob’s family aren’t related to the Black Donnellys—at one time there were a few families in the area with the same name—but the legend continues to captivate. “It’s really tough for me to order a pizza around here,” said Rob with a rueful smile. “They always think I’m joking.”

Visiting the Donnellys

- The events surrounding the story of the Black Donnellys occurred in and around the town of Lucan, 30 kilometres north of London, Ontario.

- The Donnelly grave is located in the cemetery adjacent to St. Patrick’s Church, at the intersection of Number 4 highway and the Roman Line, three kilometres southeast of Lucan. To reach the Donnelly homestead, travel seven kilometres north from the cemetery on the Roman Line. The gravel is mostly hard packed, but becomes looser as you approach the homestead. If you’re riding a big bike, stick to the tire tracks and you’ll be fine.

- It’s best to call ahead to arrange tours of the homestead. Tours are generally 90 minutes and cost $15 per person. Robert Salts (519 227 1244; rsalts@quadro.net) does a fine job of bringing the Donnelly story to life—it’s well worth the time and money. Salts sells copies of his self-published book You are Never Alone: Our Life on the Donnelly Homestead for $20.

- If you plan to stay overnight, your best options for lodging are London or Grand Bend, a popular beach town on the shores of Lake Huron 40 kilometres northwest of Lucan. A few acceptable restaurants dot Lucan’s main street.

- A small but thoughtfully presented Donnelly museum has recently opened in downtown Lucan (donnellymuseum.com). Members of the museum staff are helpful and knowledgeable, and there is a Donnelly-era log cabin on the property to explore.

- For an in-depth and entertaining history of the Donnelly family, you can purchase The Donnelly Album by Ray Fazakas for $20 at the museum. Fazakas, a retired lawyer from Hamilton, is the recognized expert on the Donnellys. Much of the museum’s collection comes from his private archives.