Big, beautiful, and bouncy: this Scrambler works

I blame beer commercials. Or maybe it was those old cigarette ads. You know, the ones where some virile man amongst men would puff on a Marlboro and then do something manly. Whatever the case, I don’t think it will come as a shock to anyone when I say there’s little — OK, no — truth in advertising.

It wasn’t always so. Back in the day, when, I guess, it never dawned on ad men that they could actually lie to the public, there was often an uncommon grain of truth in marketing. Automakers, for instance, would brag that their car had electric starting and three gears, both tangible facts easily verified by virtually anyone. Coca-Cola, meanwhile, had no compunction in telling one and all that its confectionary beverage was laced with cocaine. Hell, that’s where it got its name.

Imagine were the same true today? V8 would have to admit their drink only tastes good when mixed with Vodka and the advertising world would put out Crazy People — Dudley Moore’s hilarious but cynical look at truth in advertising — ads like “Jaguar — for men who’d like to get h#@^%$#s from beautiful women they hardly know.”

That’s a long way of saying that when Triumph announced that its new Scrambler 1200 would be able to actually, uhm, scramble, I was a little cynical. BMW, Ducati, and even Triumph itself have all made such claims — the R nineT Scrambler, the Duke 1100 Scrambler and Triumph’s own Street Scrambler — and they were as suited to bouncing over tabletops as scooters are for long-distance touring. And yes, I know you could indeed ride a Suzuki Burgman to California . . . but wouldn’t you be so much better off on a Gold Wing.

So I approached this latest Scrambler, the 1200, with more than a little suspicion. Yes, it sports a whoop-de-doo-friendly 21-inch spoked front wheel, but the spec sheet also says it weights 207 kilograms. It sounds even worse in imperial units: 455 pounds. And my gosh are those twin rear shocks back there? Twin shocks went the way of the dodo bird on dirt bikes back in the days of Suzuki’s TM250 and I can tell you from personal experience how truly awful they were.

Now here’s the thing — and, with such a build-up, I think you know what’s coming — the Scrambler 1200, especially in its “cross-over” XE guise, is amazingly capable off-road. Oh, not CRF450 or even KLX 250 capable, but, and here’s me finally getting to the point, I’d take a Scrambler 1200 XE off-roading over some of the world’s best regarded big-bore adventure bikes. Honda’s Africa Twin, for instance. Probably the R1200 GS too. Come to think of it, I can’t remember one big adventure bike — mind you I haven’t ridden all the big-bore KTMs — that was as easy to do stupid things on than the big Trumpet.

First up in the superlatives column is the Showa 47 mm inverted front fork. Of course, the thing everybody will be checking for first is whether it has a full range of adjustability. It does, preload and damping both. And for those who judge everything by spec sheet, the XE also boasts 250 millimetres of travel.

What matters more, however, is how well those 250 mils are damped. Not so dirt-bike soft that it flounces on the street, but the front Showa is lush enough that some truly nasty Portuguese bumps, ruts and semi-serious rocks never once jammed forearm or bottomed fork. In fact, almost none of the assembled journalists asked for an adjustment — a rare thing amongst the prima donnas from the States I can tell you — mainly because none were needed. Maybe Showa doesn’t have the brand recognition we all reserve for Öhlins, K-Tech, et al, but this particular iteration is truly one of the best set-ups I’ve tested. Especially considering the task at hand, i.e., controlling 207 kilograms of motorcycle being flouted off-road.

Perhaps even more surprising is the performance of those rear twin shocks I so denigrated earlier. I won’t try to tell you the arrangement works as good as Honda’s Pro-Link or a KTM WP single shock, but there’s a whopping 250 mm — surely a record for dual shocks — of pretty well-damped travel. Look beyond the obvious anachronism of a non-linked dual shock, for instance, and there’s a bunch of high tech to the seemingly dated Öhlins. Besides being adjustable for compression and rebound damping, the spring arrangement, though complicated, pretty much mimics rising-rate linkages. For one thing there’s actually two springs per shock — one soft, one firmer — and the longer, firmer of the two actually has a progressive rate built in.

But wait, as Ron Popeil used to say, there’s more! That upper, softer spring also has a plastic travel limiter that cuts out the softer rate — essentially coil binding the softer spring — so that the stiffer but still progressively wound main spring can do its thing. Yes, it seems like a helluva lot of complication just so you can remain faithful to Steve McQueen stylistically while still retaining genuinely off-road capable suspension, but Öhlins and Triumph pull it off. The rear soaks up hard bumps almost as well as the front fork, the damping is well controlled and, better yet, doesn’t go limp with heat-induced fade despite the greater strain that twin shocks endure off-road.

How good is the combination, you ask? Well, we spent pretty much an entire day pounding the big Triumphs — and, again, they weigh 207 kilos — over terrain that would threaten the toughest of big-bore adventure bikes and came away, no thanks to skill, completely unscathed. In fact, we even played — yes played, on what is, or was, a 450 pound street bike — for a little while on a full-blown motocross track. And, even though the front end washed out a couple of times (despite being outfitted with full knobby Pirelli Scorpion Rallys, 90/90-21 in front and 150/70-17 in the rear), I can report that there were no suspension-induced calamities. Indeed, any time my humbly talented self can wheelie, once again, a 207 kilogram “scrambler” off a tabletop, you know somebody got something right. Hell, I even busted a berm. I haven’t done that in 20 years! Have I mentioned that this darned thing weighs 455 pounds?

As for the rest of the 1200’s off-road nous, well, the centre of gravity isn’t quite as low as BMW’s Boxer-engined GS, but neither is it as sky high as Triumph’s own Tiger 1200. The XE’s handlebar is motocrosser-wide so there’s plenty of leverage when you need it. The big 1200 cc “High Power” parallel twin is a model of low-end torque (81 pounds-feet at just 3,950 rpm) and tractability so even though the transmission ratios are road-oriented, it’s still plenty grunty at crawling speeds. The aforementioned handlebar is well located for standing up and the XE’s pegs feature removable rubber cushions so you can gain extra traction on the serrated pegs. Triumph even engineered the XE’s brake lever so that it can be quickly adjusted, without tools, to a height more suitable for standing on the pegs. Throw in Brembo four-pot brakes — monobloc M50s, in fact — that are sportbike-spec but have the requisite sensitivity for off-road use and the package is truly impressive.

Notable, as well, in the braking department is that, like the best of bikes destined to traipse over hill and dale, there’s an Off-Road mode that lets you lock up the rear wheel while maintaining the front tire’s ABS function — albeit at a more liberal 50 per cent slip ratio rather than the Sport mode’s 15 per cent road orientation — but the XE also boasts an Off-Road Pro mode that eliminates ABS altogether. Combine all this and the Scrambler 1200 would be my choice if someone forced me to run an enduro on a stock 1,000 cc or larger off-roader (though, thank you very much, I am not accepting invitations).

OK, that’s the (surprisingly capable) dirt biking side of things. The next question I am assuming you’ll want answered is whether all that off-road nous compromises the Scrambler’s on-road performance. Why, yes it does actually, though the real question I suspect you want answered is whether all that off-road ability compromises the Scrambler’s on-road performance enough to cross it off your street/adventure/dual-purpose shopping list.

That is a more nuanced question and depends on what you really want out of a motorcycle and what limitations you’re willing to put up with to access that list of demands.

For instance, Triumph’s marketing mavens — and yes, they always eventually exaggerate — think that the Scrambler 1200 will be an option for people buying large adventure touring bikes. As good as the Scrambler is — and if you’re with me so far, you’re getting an idea how impressive the 1200 really is — it doesn’t have the comfort, the wind protection or the cargo capacity, even with the accessory soft saddlebags, for serious long-distance adventuring. A few impressionable Millennials may spring for a Scrambler over a Tiger 800, but I don’t think that, despite my contention that the Trumpet is better off-road, there’s going to be much cross-shopping with BMW’s new 1250 GS or Honda’s Africa Twin.

There’s no wind protection, for instance, and none offered beyond a teensy-tiny fly screen. The seating position is quite excellent, but the seat itself a little plank-like. There’s no quickshifter on offer, but like all Triumph’s big High Power twins, you don’t really need one, there being so much of that low-end grunt I mentioned. Besides, even if you forget to upshift, the engine is so incredibly smooth that it doesn’t affect comfort at all, it being far too easy to find yourself cruising at a buck-twenty in fourth, the free-spinning parallel twin giving no indication that you should already have upshifted to sixth. The big twin is also more than passably powerful with 89 horses available at 7,400 rpm. That might not sound like much, but those 207 kilos that seem so heavy off-road are actually lightweight compared with other big-inch street bikes.

One more thing that will further the Scrambler’s cause, especially with the aforementioned Millennial crowd (who, by the way, fawned over the Scrambler’s retro authentic styling) is how digitally savvy it is. No, there’s no infotainment system available — an audio system hardly being appropriate on a motocross track — but the digital gauge display, with Google turn-by-turn navigation system, is top notch, keyless ignition is standard, the XE boasts six riding modes. And Millennials, listen up: The Scrambler is the first motorcycle of any kind to let you control your GoPro camera — including the all-new Hero 7 with image stabilization — through its handlebar switchgear. Yes, Youtube is about to be inundated with videos of bearded hipsters endo-ing arse over tea kettle.

As for handling on road, even with its off-road(ish) Metzeler Tourances, one can fairly fly down a twisty road. Oh, the gyroscopic effect of that tall front tire slows down steering some — as does the extra 0.9 degree of rake and 32 mm longer swingarm the XE boasts compared to the XC — but it works just fine, thank you very much. It’s also worth noting that even on the long-travel XE, Öhlins and Showa have calibrated springing and damping so adroitly that there’s none of the hobby-horsing common to long-travel off-road suspension when pushed hard on the street. Yes, the front-end dives when you really get on those Brembo monoblocs, but it’s hardly debilitating. I realize that I keep on raving about the Scrambler XE but it really is an amazing compromise between off- and on-road performance, especially when you throw in the added twist of authentically retro styling.

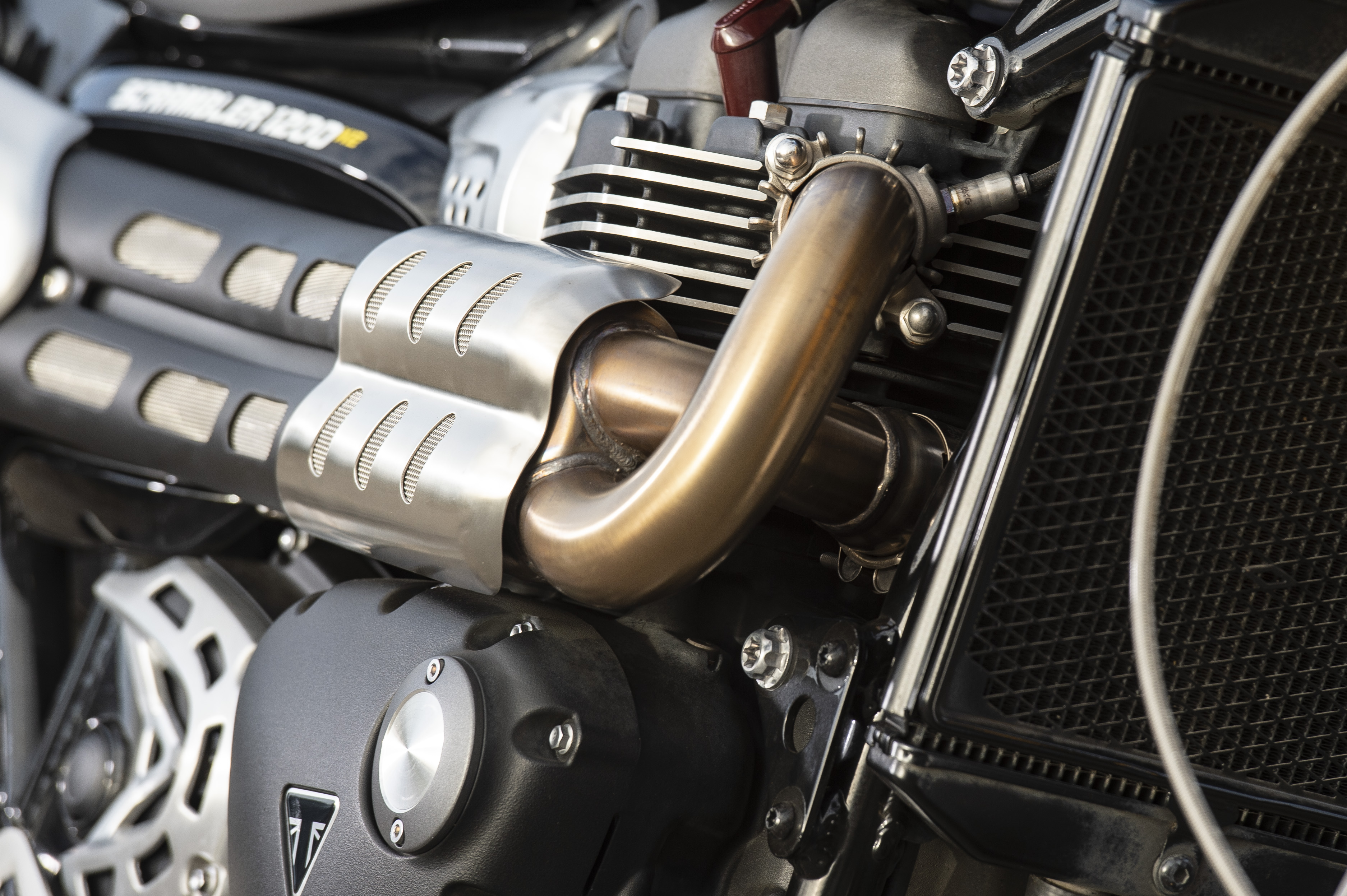

And, indeed, it is this last that will sell the bike. It’s the reason that Triumph commissioned Öhlins to jazz up some period-piece rear shocks. It’s the reason for the twin upswept pipes, the motocross-style handlebar and, what I think is going to be Triumph’s most popular option, the off-roady high-mount front fender. If the blogosphere is any indication, Triumph’s styling exercise has been a huge success.

It is also, however, the cause of the Scrambler’s touchiest — and I do mean touchy — fault. Because the 1200 needs to be Euro emissions compliant, the catalytic convertor has to be as close to the exhaust ports — to heat up more quickly — as possible. The problem is that the closest it can be fitted is right after the sweeping curves exiting the cylinder head and, unfortunately, that just happens to be where the inside of your upper right leg wants to be when riding.

It‘s not an ideal placement, fairly basting your leg in radiant heat. It never got over 18 degrees in Portugal and was raining much of the time, yet our right legs were doing a fair impression of a turkey drumstick on a Thanksgiving morning. Stoplights on a 35-degree summer afternoon are going to turn this up to a full broil. Triumph notes that removing the catalytic convertor — as the company has done on the Baja-bound racing version of the Scrambler — solves the issue but they’re going to have to come up with a better solution or risk consumer complaints.

My other bone to pick is with those most excellent Öhlins. Well damped and robust they may be, but lacking easily adjusted preload to carry a passenger is going to be a real pain in the you-know-what. A grub screw needs undoing and then you need a special preload ring wrench that you’ll only be able to use inside the fender well to turn the collar on top of the shocks. And, of course, you’ll need to do it twice. Better to perhaps buy your passenger a bus ticket.

Is either fault going to stop the new 1200 from being a success? Not a chance. Indeed, the only thing that’s going to restrict Scrambler sales is going to be price. Its styling and intent scream young Millennial, but its price tag — $15,200 for the more street-oriented XC; $16,300 for the XE we’ve raved about — is closer to Boomer territory. That said, if you’re interested in the Scrambler, I’d suggest you put a deposit down soon. They’re going to fly off showroom floors. Truly, it’s going to be a good year for Triumph dealers.

SINGLE IS BETTER

Why are twin shocks endemically inferior to linkage-based monoshocks? Well, without going into a complete engineering thesis, it all comes down to wheel travel and piston speed. Basically, a twin shock has to move about the same distance as the wheel travels. That’s especially true in the case of the Triumph Scrambler’s rear Öhlins, which are mounted just forward of the rear axle. Every millimetre the wheel travels — 250 mm in the XE’s case — requires the shock’s piston to move almost the same amount.

Shocks in a monoshock linkage arrangement, meanwhile, travel much less. That’s an advantage for two reasons. The first is that all that movement causes the damping oil to heat up, the reason why twin shocks have traditionally always faded much more quickly than monoshocks when stressed and pushed hard. The other factor is that all that movement requires that the piston move more quickly. Dampers of any kind are much more easily controlled when they move slowly through shorter distances. Damping force increases with the square of velocity, so the faster a shock moves, the more difficult it is to modulate compression damping.

2019 Triumph Scrambler 1200 XC

Like so many motorcycles today, Triumph’s Scrambler is built on what manufacturers — automotive and motorcycle alike — call a platform. Design a basic chassis, engineer a “family” of engines, and then mix and match to your heart’s content.

So, it’s a little surprising that the XE and XC share most of their componentry: Triumph’s High Power version of its 1200 cc parallel twin, piggyback Öhlins shocks, Showa USD front fork, bodywork, TFT gauge set and even that Millennial-tempting, Bluetooth-connected GoPro controller on the Scrambler’s left handlebar.

What is surprising is how much different the XC feels than the XE. Oh, the 89 hp High Powered engine sends common cues and those incredibly powerful monobloc Brembo M50s still generate enough Whoa Nellie power for a topline superbike, but don’t mistake similarity for duplication.

For one thing, even though they share Showa front forks, the XC rides on 45 millimetre fork and like the Öhlins in the rear, their travel is reduced from 250 mils to 200 mm. Triumph says the spring rate is the same, but the damping rates have been modified so that neither fork nor Öhlins bottoms out on whoops and sharp-edged bumps.

Yes, the XC is meant to go dirt biking on too! However, Triumph sees its purview as less stand-on-the-pegs motocrossing and more old-fart riding it out in the saddle. Triumph’s marketing mavens call this, wait for the incredibly obvious, “scrambling,” and just to prove that that is a thing, they roll out lots of pictures of Steve McQueen and Bud Ekins riding off-road with buttocks planted firmly in the saddle.

If that describes your riding style, maybe the XC is a better choice for you. Certainly when we were playing on the relatively smooth flat-track portion of Wim Academy playground in Portugal, the XC was the ride of choice, its lower centre of gravity, stiffer suspension and tighter steering — there’s 0.9 degree less rake and the swingarm is 32 mm shorter — better for foot-down sliding. And, truth be told, the XE’s 870 mm seat height isn’t going to be for everybody, the XC’s 30 mm lower perch allowing a much wider audience to sample scrambling, Triumph style.

That said, I much preferred the XE. Off-road, the suspension was noticeably cushier. On-road, its steering was more neutral, the XC seemingly not as happy with its tighter rake and 8.2 mm shorter trail. It wasn’t at all bad, but compared to the linear XE, the XC does fall into corners a little at low speed. Throw in a handlebar bend I found awkward — there is an optional 10 mm riser, however, to alter its height — and I much preferred the XE.

That said, the XC is still more off-road friendly than anything else wearing a Scrambler tag, looks fetching in its Khaki Green livery and mated to the Escape inspiration kit — leather panniers, rear rack, fly screen, centrestand and handlebar brush guards — makes a passable weekend tourer with a penchant for deep woods adventuring. It’s also $1,100 cheaper than the XE.

Nonetheless, if it were my choice, I’d opt for the full-boat XE. If you’re buying into this whole 1200 cc dirt bike thing, you might as well buy the whole enchilada.