Ducati chose Sardinia, off the west coast of Italy, for the world press launch of the Hypermotard 1100. Quaint villages are strung together by sinuous country lanes, which wind through the surrounding countryside crossing farmland, mountains and valleys. The area is steeped in history, and by the roadside are ancient ruins. It is serene and picturesque. But Ducati could have chosen nearly any location for the release of this machine; I’m having so much fun pitching it about the only scenery I focus on is the next fast-approaching apex.

We’re sprinting through the winding roads 30 km/h over the posted limit, some riders ahead of me lifting the front wheel high between turns, when we rush up on a Land Rover with blue lights on the roof and “CARABINIERI” written boldly across the tailgate. We’re busted, I think, as a series of brake lights ahead of me shine and machines nosedive, bunching up behind the rolling roadblock. Then, our Italian lead rider pulls out across a solid centre line and passes the Land Rover, picking up the pace again. We follow. I figure he’s either under the Hypermotard’s trance and has been fully delinquecized, or police just aren’t as zealous here as they are back home. It turns out to be the latter, but his brazen disregard for authority could have easily been because of the Hypermotard’s bad-boy influence. The Carabinieri later catch up with us during a photo shoot and show more interest in the Hypermotard than in our shenanigans.

First introduced as a concept vehicle at the Milan International Motorcycle show in November 2005, the Pierre Terblanche-designed Hypermotard won Best of Show. Ducati immediately capitalized on its ensuing popularity, taking the bike from concept to production in 18 months, a record for the Bologna manufacturer. Whether you love it or hate it, the Hypermotard is a stunning motorcycle. Based on the Multistrada, it is stripped of unnecessary hardware and uses clever integration of components, like a tailpiece that doubles as a passenger grab handle and hand guards with integrated LED turn signals and mirrors that disappear once folded back for track use. And Ducati intends the machine be used on the track, as the rubber footrest inserts are removable, exposing serrated edges for a surefooted grip. The footpegs also include Teflon sliders, so as not to mar the racetrack surface, and the cast passenger footrest brackets are easily removable, as is the aluminum sub frame, which can be replaced if bent.

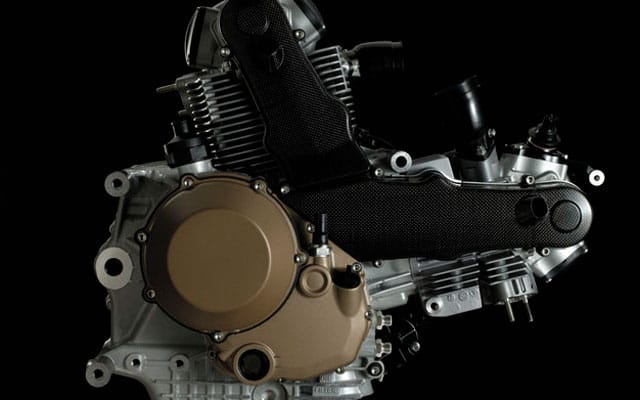

Straddling the machine almost feels like getting on a dirt bike; it is narrow with an upright seating position, and a high and wide tapered handlebar. The machine is so compact it is barely visible once seated if you’re wearing a full-face helmet. The seat is narrow and blends smoothly into the slender, if small, 12.4 litre fuel tank (7.6 litres less than the Multistrada) making it easy to slide forward to transfer weight. Seat comfort remains to be seen, because I spent very little time perched in one position, but I’m guessing it will carry you comfortably between fuel stops, which as suggested by the limited fuel capacity, will come often. I’m also guessing the typical Hypermotard owner won’t give a rat’s ass about posterior comfort; so much fun will be had that the brain will block out all unpleasantness. Once fired, the exhaust note is subdued yet rich, and is accompanied by the familiar Ducati dry-clutch clatter. The Multistrada uses the same dry clutch as the 1098, as opposed to the Multistrada’s wet clutch. One extra friction plate in this latest dry clutch allows the use of lighter springs and lever effort is the lightest yet on a big-bore Ducati. But that’s the practical reason given for the oil-free clutch; Hypermotard project manager Federico Sabbioni also felt hardcore Ducatista associate a dry clutch with high performance, while it adds the appropriate amount of mechanical roughness to reinforce the bike’s hooligan image. The 98 x 71.5 mm 90-degree twin revs freely and quickly and has a fat midrange. Ducati claims 90 hp at 7,750 rpm, and an impressive 76 lb-ft of torque at 4,750 rpm from the 1,078 cc air-cooled engine. Immediately leaving the hotel parking lot, I blip the throttle in first gear and the front wheel snaps skyward. A second-gear blip produces the same result—this is going to be fun.

We’re heading to Autodromo Nazionale Franco di Suni, commonly known as Autodromo Mores because of its location near the village of Mores. The racetrack is 95 km from our beachside hotel, allowing some street time on a standard Hypermotard before afternoon racetrack sessions on a kitted S model. In stripping the ’Strada, engineers were able to shave 17 kg (37 lb), the Hypermotard tipping the scales at 179 kg (395 lb). The S model loses another 2 kg due to lighter Marchesini forged wheels and carbon-fibre bits. Another benefit of this leaner design is that although overall gearing is identical to the Multistrada, the Hypermotard feels like it’s geared shorter and accelerates with more vigour, lifting its front wheel with ease on uphill stretches. Handling is light, the bike responding with precision while trail braking deep into turns. Despite the wide rubber-mounted handlebar, stability is excellent and front-end feedback direct. Nailing the throttle exiting slower turns lightens the front end, but the bike continues where pointed, exhibiting no understeer. Tight switchbacks are handled with utmost ease despite the bike’s tall stature. The Hypermotard is much more nimble than the Multistrada due mostly to its reduced weight. Suspension travel is identical to the Multistrada, with 165 mm at the front and 141 mm at the rear, though spring and damping rates are altered to compensate for the Hypermotard’s lighter weight.

Riding like idiots on public roads is amusing, but the real fun begins at the racetrack. Immediately noticeable on the S model is the raised rear end. Upgraded features on the S include adjustable rear ride height, an Ohlins shock instead of the Sachs unit, DLC fork slider coating, monobloc Brembo front calipers borrowed from the 1098, and Pirelli Diablo Corsa tires in place of the Bridgestone BT-014s. Strictly for our amusement, the S models are equipped with full Termignoni racing exhaust systems, available through the Ducati accessory catalogue. The added 5 horsepower and 2 lb-ft of torque might seem insignificant, but the spread of torque is much broader and elevates the Hypermotard from juvenile delinquent to full-blown career criminal. Even in modified form it lacks the muscular top-end rush of the KTM 990 Super Duke, though power comes on much harder at lower rpm, lifting the front wheel often at the exit of the circuit’s slower turns.

The 1.65 km Mores circuit is tight, not unlike Shannonville’s Nelson circuit but smoother with slight elevation changes, and is the ideal venue on which to exploit the Hypermotard. As a track day mount, it reigns supreme; there’s no bodywork to mangle in a fall, and it can be thrown around aggressively—and entices you to do so by providing confidence-inspiring feedback. The upgraded suspension components on the S are firmer and better suited for an all-out racetrack assault than on the standard model. There’s no twitchiness present in the chassis, even on an uphill chicane where the front tire momentarily leaves the pavement in the transition. The front end can be pushed into a corner to the point of losing grip, and the front tire does occasionally scrub through some of the tighter turns, but the bike follows through maintaining its stellar front-end feel, attributable to the exceptional grip from the Pirellis. Monobloc brakes provide remarkably strong stopping power without fading, though on the street, the regular two-piece Brembos on the standard model were more than sufficient.

The Hypermotard blasts across the short straights and through turns with the agility of a big single, but with lots more power. On a longer course, higher speeds will likely reveal its lack of streamlining as a speed limiter, but on this racetrack, where 170 km/h is the top speed, it is a pure marvel to ride. The biggest limiting factor to the Hypermotard’s racetrack performance is limited cornering clearance. Although nothing touched the ground while blitzing through Sardinia’s countryside, on the track, footpegs, the brake and shift levers and the sidestand grind regularly, albeit at extreme lean angles. A compromise was made for added legroom at the cost of reduced cornering clearance. Perhaps a better compromise would have been adjustable peg mounts because the Hypermotard feels very comfortable at full lean, inviting its rider to test the limits of traction.

To everyone’s chagrin, track time is limited to two 10-minute sessions, though only four journalists are allowed on the course per session, providing a clear racetrack. A fifth rider joins us during our brief sessions: current World Superbike competitor Ruben Xaus, who rides a 999 for team Sterilgarda. One surefire way to make even the most headstrong motojournalist feel insignificant is to allow a rider of Xaus’ caliber on the track at the same time. While I’m hard on the binders, forks bottomed and rear end wiggling going into the first turn, Xaus drifts by me, knee down and sideways on the inside, running deliberately wide at the apex so as to leave enough room that I can complete my turn undisturbed. Xaus repeatedly takes the first turn, a 180-degree second-gear left-hander, in this manner while journalists do their best to imitate, hopping, skipping and tail-wagging into the corner under the scrupulous eyes of their peers. Wanting to keep my integrity intact, I choose to experiment backing it in at the far side of the racetrack, out of sight. Using the clutch and rear brake, I manage to get the rear wheel slightly out of line smoothly on a couple of occasions going into a slow downhill left-hander, but with nowhere near the finesse, speed, or outright coolness of Xaus.

Minimalist instrumentation includes a digital tachometer, which is nearly useless, though engineers had the foresight to include a highly visible programmable shift light. For the serious track rider, both models are Ducati Data Analyser (DDA) ready. DDA, a feature introduced on the 1098, records up to 2 MB of data, including throttle opening, road speed, rpm, engine temperature and distance travelled, and records laps and lap times for later scrutinizing by expert benchracers, though it does remove the possibility of exaggerating one’s racetrack feats.

The Ducati Hypermotard is not everyman’s machine. Not quite as focused as a supersport, it is more enjoyable to ride over a wider variety of roads, yet offers no more in terms of practicality. If you are rational about your purchases and expect a polyvalent motorcycle, look elsewhere. It will, however, transform even the mildest-mannered citizen into a trouble-seeking malefactor, so if you’re experiencing a midlife crisis, or looking to have one; at $13,995 ($17,995 for the S model) the Hypermotard costs less in the long run than cheating on a spouse with someone half your age. And if the fun factor ranks as high on your list of priorities as eating, it will fulfill. We plan on testing the Hypermotard more extensively in the near future—and we promise, we’ll behave.