With Edelweiss in the Alps, life’s a picnic

The ride up the Stelvio with its 48 turns as sharp as the blades of scissors is the kind of motorcycling challenge that I hate because I know I’m going to try it and I’ll probably blow it. Any failure of confidence here, where you’re constantly climbing toward the 2,750 metre summit and where you’ll make a tight uphill turn 48 times in order to get there, will be your ruination, and there’s a real potential for embarrassment so severe that you could actually die from it. Also, of course, you could get hit by a bus.

And yet it’s the ride down, not up the Stelvio, but down the other side, where the chance of stalling in the middle of a turn is less than the chance of seeing angels dancing on the head of a pin, that the entire tour’s most frightening and most dangerous moment occurs. And as I watch the riders in front of me try to pass a stopped car on this one-lane road with a mountain on one side and nothing but gravity on the other, I’m acutely aware that in a few seconds it’ll be me on that asphalt tightrope.

It’s Gary and Alvin ahead of me on an R1200RT. Gary is a swaggering Texan and Alvin is whatever the opposite of “swaggering Texan” is. I find that I take to Alvin — who speaks too rapidly for me to hear half of what he says but who is as cheerful as he is likeable — right away; but Gary, well, he takes some getting used to. He reminds me of Robert Duval in cowboy boots and a Stetson, only it’s motorcycle boots and a Shoei, and I just know that one fine morning I’m going to hear him tell me how much he loves the smell of napalm, but the first time I actually hear him speak he is bitching about a rider who wedged himself ahead of him. “Hey, I don’t mind ridin’ behind somebody who can ride, but this guy’s blah blah blah,” I walk away, thinking two things: (1) he’s right, it’s annoying as hell when somebody slow gets in front of the fast guys, and (2) he really doesn’t look like somebody who rides fastly; so we’ll have to see about good ol’ Gary.

By the time I observe him threading that needle between a stopped car and an abyss I’ve come to understand Gary a little better, and I like the guy quite a lot. Brash, sure, but he’s fair, if you know what I mean. Also, the slower riders have learned to let the faster riders go by, and Gary is, indeed, one of the fast riders.

Speaking of which, Wim and Claudia are as fast and smooth as I’ve come to expect in Edelweiss tour guides. Wim is Belgian, does not like chocolate, and to my delight he smokes cigarettes during photo and coffee breaks. Claudia is German, works part time for Edelweiss, and has one of the most attractive helmets I’ve ever ridden behind. The first time I see her, I’ve just arrived in Erding, Germany, from Collalbo in the South Tyrol of Italy, after a four-hour rail trip. I had stepped off the train at Erding, which is very near Munich, and, before I could even think about finding a taxi, I heard someone saying, “Sir? Sir! Are you here for Edelweiss?” It was Claudia, who had just taken a group of riders (part of the group I was there to join) on a city tour, and for some reason she had stopped at the Erding train station, and was on the platform not even 10 metres away as I was getting off the train, obvious in my Alpinestars jacket and towing an Ogio gear bag. “Hop in,” she said, and I heaved a sigh of relief. There are few sounds quite so welcome in a country where you’re a foreigner without a map as “hop in.”

In the Edelweiss van I was introduced to Ducati Jane and a few others. Huh, I thought. Ducati Jane. We’ll see about that. As it turned out, Ducati Jane really is Ducati Jane.

TUNNEL TO THE SUN

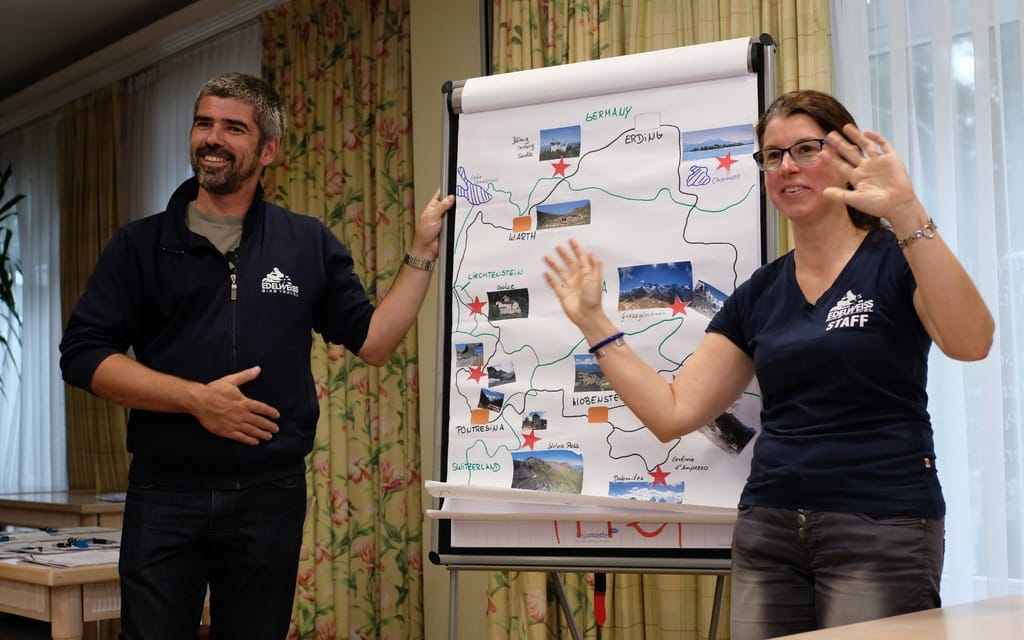

Sunday morning, September 3. Wim and Claudia delivered a morning briefing at the Henry hotel in Erding. The two tour leaders were accompanied by Dieter, a tall, easy-going German who smiled a lot and would drive the blue Edelweiss support van. Wim and Claudia described the routes we would follow, the passes, the five countries (Germany, Austria, Italy, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland) and some of the European driving rules. Wim’s iPad showed a highway-camera view of an Austrian pass we were scheduled to hit that afternoon, the Großglockner (that ß is a German double-s), and, perhaps unsurprisingly in early September, the 3,800-metre-high road was snowed over. It’s a spectacular pass, and it was disappointing that we would have to divert to another route.

We were a large group — 16 of us plus the tour guides — so we split in two, and I rode with Wim’s bunch. It turned cool and wet as we travelled south and east through Germany and into Austria, and when we stopped to put on rain gear I feared that the summery weather I had experienced the previous week in Italy had come to a dark and uncomfortable end. Soon after that we arrived at the 5.3-kilometre-long Felbertauern tunnel in southwest Austria, not far from that wintery Großglockner pass that we had to forgo. We stopped by the tunnel’s northern entrance — with snow all around us, though the pavement was clear — and soon after that Claudia’s group arrived. They didn’t stop, and Claudia, noticing that Wim was holding his iPad up, posed for him as she rode by. Coincidentally, I had my camera ready, and I shot from the hip and nailed her.

We mounted and followed Wim into the tunnel, and for five kilometres rode through this gigantic hole in a mountain. The Felbert and other tunnels we encountered (and that I had ridden through a week earlier on an Alps Riding Academy tour) have fire stations about every 500 metres with emergency exit doors, and opposite them are signs telling you how far you’ve come from the entrance and how far you have to go to the exit. Some long tunnels have pull-outs for broken-down cars, and even side roads that lead off to some other part of whatever mountain you’re boring into.

We exited on the south side of the Felbert, still in Austria, but now a completely different environment as we rode into a sunburst of green and warmth. I stopped to shoot a photo, willing to risk being left behind, but a little extra speed brought me up to the group again in 15 minutes. Although I hit close to 160 km/h chasing them, I collected no speeding tickets, which in Austria are inhumanly expensive.

We spent that night in the Traube hotel in Lienz, a city near the line between southern Austria and northern Italy. I don’t remember much about it, but I do remember an amusing breakfast conversation between American, German, New Zealand, and Canadian members of the group as we discussed gun control, medical systems, and something the Americans in the group insisted was called “freedom.” The conversation was brisk, but punctuated with laughter.

The following morning we left for Italy, and a hotel that I had called home the week before.

SUNNY SOUTH TYROL

I had ridden with Wim’s group on Sunday, so on Monday I switched allegiances and went with Claudia. We headed southwest into Italy and an area of sharply peaked and ridged mountains called the Dolomites, which Wim had told us were considered “Europe’s motorcycle playground.” This was where I had practised with the Alps Riding Academy the previous week, and I looked forward to it. There were passes — the Sella, the Gardena — which I hardly remember, because the roads in these mountains are sensational, stunning the rider with kilometre after kilometre of S-curves wrapped in spectacular mountain scenery, so much that you’re overwhelmed, and it’s only later that you realize you’ve had the ride of your life.

Our destination was Collalbo, a village high in the hills above the larger town of Bolzano, but we stopped for lunch at a place in the mountains near a World War II bunker and enjoyed a picnic that Dieter, after driving ahead of us in the van, had set up. It was an odd place, beautiful and rugged, and kind of funny. “One five hundred pound bomb,” Larry said, eyeing the bunker, “would take care of that.” Larry is a Vietnam veteran who knows something about dropping bombs and flying jets, so I believed him, but if the bunker made a poor shelter from enemy aircraft, it was a fine toilet, and the view from the piss stall reminded me of the sights you might find in British Columbia on a mountain hike.

We parked late that afternoon at the Bemelmans Post hotel in Collalbo. The hotel is superb, has a gorgeous view, is near some wonderful tourist attractions including an aerial cable car ride down to Bolzano, has a very relaxed German shepherd hotel mascot that’s always around and never bothersome, and is blessed with a patio overlooked by a suffering Jesus Christ. We sat around nursing beers and Cokes and chit-chatted, and at one point, Ducati Jane remarked that I hadn’t enjoyed following her that afternoon. I responded, honestly, that I had no objection to sitting on my GS behind her, none at all, even though she was on something other than a Ducati, as were we all that week (word is, weeks after the event, that Jane liked her GS700 so much that she’s bought one in New Zealand, though she’ll hang onto the Duc, too). Anyway, after I said that I would ride behind Jane any time, Wim said, in a soft voice, “You know how to handle a bike.” I don’t know exactly why he made that coment, but even 50 years after I started riding motorcycles, the compliment, from someone who’s job it is to watch people ride motorcycles, pleased me.

The next day, Tuesday, Sept. 5, was a rest day, but most of us headed out for a ride in the Dolomites. We climbed to a hilltop restaurant along a narrow road that turned onto a more narrow, twisted, and muddy road decorated with branches and construction machinery, and there one of our riders lost traction and fell. No injuries, no damage to the bike, and our tour guide seemed unconcerned. The rider got the bike back up, remounted, and we continued to the restaurant, where we enjoyed coffee and snacks on a terrace with a magnificent view.

Sometime later, around lunchtime, I guess, we mutinied, voting en masse to return a little early to the hotel. The riding had been fabulous, but enough, even of a good thing, is sometimes enough. On the way back, we stopped at a gas station to refuel — it’s an Edelweiss obsession, you refuel each day before parking your bike, even if you’re tired and your butt hurts, which pretty well describes me whether I’m riding or not — but the attendants were having lunch, which is an Italian obsession — you close up shop and retreat to a five-course meal for two hours, and screw the customers, even if their gas tanks are empty, which pretty well described all of us. The solution for gas station needs is credit-card-operated fuel pumps, but these require credit cards with PINs, which some of us didn’t have. The solution for that is cash: you stick a 10-euro note into the machine and it gives you some gas. Unfortunately, you might or might not get the gas, and you might or might not get a receipt. Wim didn’t get a receipt, and Larry didn’t get any gas, despite each of them stuffing euros into the machine. Wim hailed one of the attendants, who came out, thoroughly pissed off, and gave Larry his 10 euros back. Larry eventually convinced the gas machine to cooperate.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, THE STELVIO

Wednesday, Sept. 6. The Stelvio was the only thing on the minds of most of us as we set out on Wednesday morning, and for good reason. I had been warned by David Booth that the bike I had chosen for this week, a BMW R1200GS, was too big, too heavy, and altogether too much for the curves on passes like the Stelvio. Admittedly, he was right, sort of. The Beemer is a big bike, and the curves on the Stelvio are tight, dangerous, and technically challenging. Take a right curve in the mountains of B.C., cut off the curve part and make another curve entirely within the space of the two lanes that formerly led up to that other curve, then stick it at a 10-degree uphill angle. The Stelvio’s curves are worse. However, the R1200GS was indeed a fine motorcycle for such a challenge. A little tall for me, but so’s a kitchen chair, and its balance and low-speed manoeuvrability are a lesson in perfection. I doubt that you can find a better motorcycle for that kind of riding.

The Stelvio’s uphill hairpins come at you slowly, and it seems there’s always another one ahead. The road, like that of other passes in this part of the world, was created when horse-drawn wagons were used to carry freight and people, and horses can pull wagons up hills with limited steepness, so the way to get to the top of a mountain is to go zig-zag, which allows horses to survive the climb and motorcycle riders to either scare themselves silly or enjoy themselves more than any legal activity should allow.

I was, frankly, nervous about each and every uphill right-hand son-of-a-bitch hairpin turn that I came to, and yet, I managed all of them, without straying very much or very frequently into the other lane, and without stalling, falling off the mountain, hitting an oncoming car in the middle of a turn, or even putting down a boot. There are 48 hairpins; I’m not sure how many are right-hand, but lots; I lost count somewhere after five; and before it seemed that we had gone through 48 we were there. At the top. Having conquered the Stelvio. I felt good, though not quite ready to go out and beat up Vikings. Still, the gigantic weiners on gigantic buns that Bruno served off his outdoor grill for three euros were about as good as food gets. Until, of course, mine slipped out of the bun half eaten and landed between my feet.

It felt good to be at the top of the Stelvio, and we were there with bicycle riders, sports car drivers, bus passengers, and even skiers, strolling among souvenir shops, eating, taking in the sights, taking selfies, taking selfies of other people, and thinking about Facebook entries. We had ridden up one after the other, about 20 metres apart, and I think I followed Mike and his wife Alicia, the youngest people on our tour. Mike is a funny guy who works in construction and doesn’t look it, and he’s the son of Big Mike, who is also a funny guy and does look like someone who works in construction, though he does work, at least part time, as a piano player in a pub. One night — possibly that night, in a lovely Swiss hotel, Big Mike entertained many of us with a round of piano tunes that he accompanied himself on, doing, for instance, “Hotel California” as a polka, but also doing credible renditions of some Billy Joel and Elton John tunes that everyone knows and most people love. It was a blast sitting there while he pounded out tunes and belted out songs for us, and I was stunned that this big, funny, fast motorcycle rider was also a wonderfully entertaining musician. It takes all kinds, and that’s one of the things you find on an Edelweiss tour.

Meanwhile, back at the Stelvio, we had a hill to get down from. I followed Gary and Alvin on their R1200RT, and the road down was easier than the road up, possibly because the curves were looser, but more likely only because there was no danger of stalling, as I said at the beginning of this tale. We were moving around the side of a hill with a steep dropoff on the right, going a bit leftward, when the road narrowed. Along came a car, and seeing us, the driver wisely stopped, pulled as far to his right as he could manage. Gary and Alvin squeezed by without room to spare; the drop on the right was not a sheer cliff, but you’d fall with your motorcycle for a long, long time before you stopped moving. And the space left by the car was so narrow that I thought Gary would reach out his left hand and grab the car top for security as he went by. But he made it, and later, Alvin told me he had closed his eyes and simply hoped for the best. And then, of course, it was my turn, and there was nothing for it but to point the big R1200GS at the little bit of safety that remained in front of me and go for it.

There was more, of course. An Edelweiss week is not short on adventure, scenery, or riding pleasures, and nor is it short on other pleasures, like dining out and enjoying the company of other motorcyclists. There are people I haven’t mentioned — Jeff and his wife Arla, Horace, Dean, Dave and his wife Donna, and Scott (the other Canadian) — and people who were not mentioned enough, Larry, Jane and Murray, Mike and Mike and Alicia, Gary and Alvin — only because there is much to say about a trip like this and a limited number of pages in which to say it (though this story will occupy more Cycle Canada pages than most). There was Wim, and there was Claudia, and there was Dieter, and there was the arrival at the hotel in Switzerland (I think; I was often confused) when Dieter opened up the back of the van and revealed a large supply of beer and everyone gathered for a few minutes after the day’s ride and celebrated the facts that we had made it, we were there, and we were together. And that, in a nutshell, is Edelweiss.