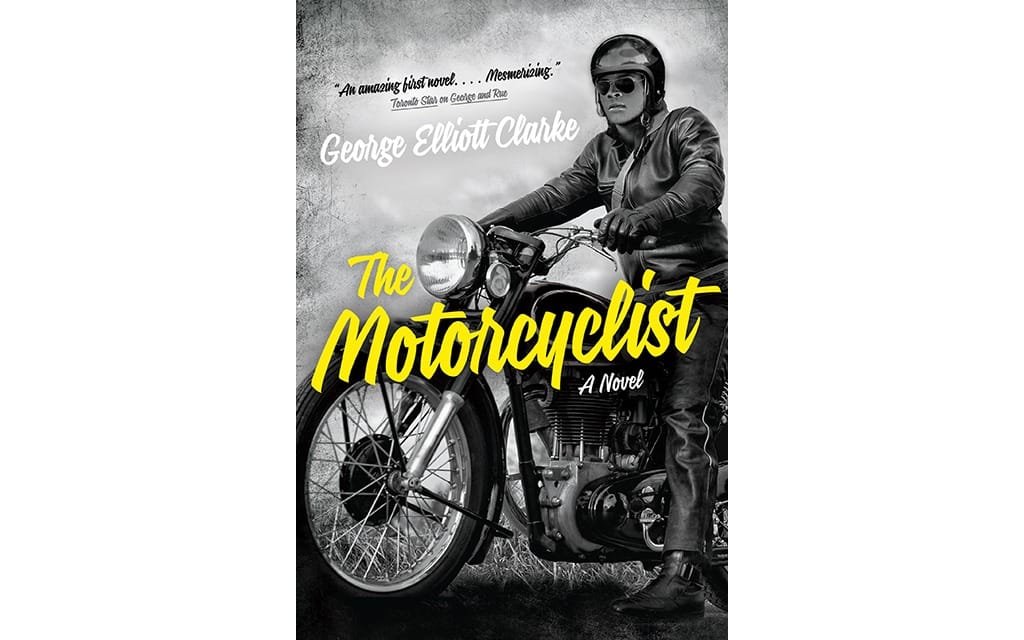

In this stunning novel, George Elliott Clarke’s father, a black motorcyclist in 1959, seeks love in the wind

Neil Graham and I met George Elliott Clarke a few years ago at an event in Toronto after Cycle Canada was nominated for a National Magazine Award. In a room full of self-congratulatory strangers, there was Clarke leaning against a railing, thumbing through a book, all by his lonesome, appealingly separate from all those fashionable knobs. “What are you doing here?” I said. He had won an award for poetry the previous year—and, as it turns out, is currently serving as Canada’s Parliamentary Poet Laureate. The guy can write. Neil sauntered over to us, and soon after that Clarke was enlisted to pen a story for Cycle Canada (“Black Cat and a Purple Beemer,” March 2012). He was a lucky find for the magazine.

That CC story was about his father, Carl, who in 1959 was a black motorcyclist in Nova Scotia. In The Motorcyclist (HarperCollins, 2016), Clarke has wrung that story out, novelized a diary that his father wrote in the year of George’s conception and left for him to read. It’s the story of a 23-year-old Negro man trying to do more than simply exist in a time and place when people like him were expected to serve, and to act with servility—and, if they were young and female, to silently accept the gropings of their white employers. But Carl is not the kind of man to simply accept—he’s handsome, vigorous, smart, and horny as a black cat on a moonlit night. Carl also is the owner of a BMW R69, Liz II, “the first brand new BMW in Nova Scotia . . . a shining, purring thing!” Throughout the book, as Carl chases love and finds sex, the BMW and he are paired in identity; the motorcycle is part of who and what he is. It lends him a kind of power that he relishes. But Carl is, psychologically, in a state of turmoil, using women but incapable of experiencing love. “Like quicksand, he empties himself into ladies’ laps but remains as self-contained as an hourglass.”

George Elliott Clarke is not a motorcyclist, and at times it shows (Carl feels the nipples of the woman on the pillion poking through his leather jacket), yet he has managed to instill an air of authenticity about the motorcycling scenes. The Motorcyclist is written in a poetic style—you can picture George biting words out of the air and tasting them—and the book is lustful, unashamed, and unflinching. (In one scene, a young woman is practising her unrealized skills with a tube of pepperoni.) The opening of the book is a statement about the uncompromising nature of pavement, “hard, serious . . . You need a cold eye, a clear eye, to avoid the random annihilations that pavement permits.” In two depictions of motorcycle crashes, the results are described in cringing detail, but most of the writing about motorcycling itself seeks to reveal the glory of it, the power and freedom and grace and, especially, the sensuality of it.

George Elliott Clarke is a brilliant writer and an extremely smart man. If you want to read about motorcycles and riding, look elsewhere, but if you want to read a brilliantly literate, sometimes frightening, always revealing novel about what it was like to be young, handsome, horny, and black, and a motorcyclist, in the Canada of 1959, read The Motorcyclist.