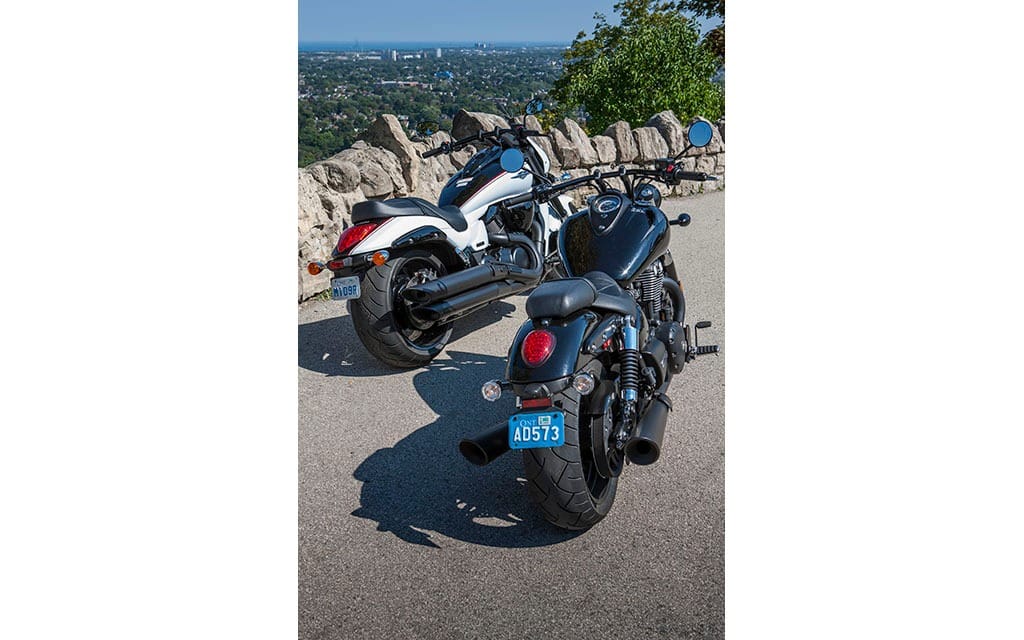

Suzuki and Triumph tackle the power cruiser tangentially

Unlike the dinosaurs that once roamed the earth—and that serve as inspiration for the power cruiser category of motorcycle—the power cruiser is not at risk of extinction. As long as men rub their bellies and mix rum with Coke and taint the air with cigar smoke, the power cruiser will endure. But what exactly is a power cruiser? The power-to-weight ratio certainly isn’t cause for distinction—it would take the Rolls Royce Griffon from Miss Supertest to allow power cruisers to rub power-to-weight noses with a sportbike like BMW’s S1000RR. We must seek an interpretation of power as applied to the cruiser.

The concept of soft power (the wielding of power via shared values rather than through coercion or deceit) is too subtle a notion to fly with machines as unabashedly brash as the power cruiser. The power cruiser is about power displayed—the swollen bicep, the stretched limousine, the turreted and columned mansion plunked in a suburban field. And when it comes to hard power, the Suzuki M109R flexes bigger and brasher than any other.

The M109R’s full name reinforces this: Suzuki Boulevard M109R BOSS

The suffix stands, its manufacturer claims, for Blacked Out Suzuki Special.

But of course that’s not what it means at all. As anyone who’s ever been employed knows, a boss is a person who makes your life hell. They ask you to do things. And if you deliver the minimum to retain employment, they ask you to do it again. Buying the M109R makes you the boss. No more answering to anyone. When you’re in the saddle of the M109R you’re in control, and to extract revenge you can fillet your boss with a keen knife and serve him thinly sliced like prosciutto (alongside olives, bread, and sharp cheeses). Furthermore, you’re boss of the boulevard—if you’re unhappy with anyone they’ll learn about it moments before they sink to the bottom of the St. Lawrence River with feet ensconced in cement.

Opposing the Suzuki in this tussle is the Triumph Thunderbird Nightstorm. Thunder and storms. At night. You know where this is headed: Wagner. We’ll pick it up where Siegmund stumbles though the unknown forest. He’s lost his shield and spear, he’s knackered, and he comes upon a dwelling and enters. No one is around. He collapses upon the bearskin rug at the hearth and sleeps deeply. Sieglinde, meanwhile, assumes she’s heard her husband return home from the graveyard shift and pays no heed. But when she enters the room, she’s startled by the stranger, and then suffused with immense pity when, upon waking, he relates his history of woe. Siegmund and Sieglinde notice that their nostrils flare in a similar manner, though neither comments.

Seigmund, learning of the imminent return of Sieglinde’s husband, wisely bolts for the door, but she stops him and claims that her husband will take pity on a defenseless soul. Seigmund, as men smitten are wont to do, resumes his place at the fire and inflames the fortunes of fate. When Hunding (the husband) enters, he is confused—understandably. He sees his wife, he sees a stranger, and he notes the odd but unmistakable synchronicity in the movements of their nostrils. And then he determines Seigmund is his enemy. Hunding is bound by honour to allow Seigmund sanctuary for the night, but challenges the defenseless interloper to a duel at dawn. And then Hunding paddles off to bed. But Seiglinde has drugged his evening Grolsch, and with Hundling in deep stupor, she appears to Seigmund in iridescent white lingerie, tips him off about the location of the hidden (and magical) sword, and then, in what may be the highlight of a very full day for Seigmund, ushers him into a spring garden lit by moonlight.

But why, you ask, not include Triumph’s Rocket III, instead of the Thunderbird, in this comparison? The Rocket III’s 2,294 cc three-cylinder engine is substantially larger than the 1,699 cc parallel twin of the Nightstorm or the 1,783 cc V-twin of the M109R. The trouble is in the three. Seiglinde’s buxom twin-peaked bosom (between which rivulets of sweaty desire run) and the duel to which Hundling challenges Seigmund are thematically twinned ideas. Good and evil, friend or foe, man and wife. (Not man and wife and man on the rug by the fireplace.)

The $16,800 Nightstorm’s Wagnerian gloom is relieved only by touches of chrome. And you know what inspired those twin headlights. Triumph says the engine is “laid-back but underpinned by serious power.” How much horsepower? They say 98, and, more importantly for a 339 kg motorcycle, 115 lb-ft of torque at 2,950 rpm. Suzuki doesn’t publish horsepower, but the $16,499 M109R jumps ahead with glee when the throttle is nailed and at idle burbles like a locomotive at rest on a siding. Themes of wanton manliness continue in the cockpit. The large-diameter handlebar grips are like latching onto a log, and the broad clutch and brake levers are ideally proportioned for hands the likes of which humanity has not seen. And since a light clutch pull would coddle a rider inappropriately, both bikes have ferociously combative clutch springs that stress the hand excessively. (This is not of necessity, but of choice—motorcycles with half-again as much horsepower and nearly as much torque have clutches of feather-light operation.)

Each bike transitions through its transmission smoothly, though the Triumph’s tall sixth gear (the Suzuki has five speeds) gives it a more relaxed gait at speed. And, as its paintjob would suggest, the Suzuki has the advantage in pure acceleration (despite being slightly heavier), though both bikes will get down the road chop-chop. But then there is the issue of slowing. While the Suzuki’s brakes are OK, its Tokico calipers can’t match the bite of the Triumph’s front Nissins and rear Brembo. Antilock braking is unavailable on the Suzuki but stock on the Triumph. Oddly, since its appearance would suggest the opposite, the Suzuki has more rear wheel travel, 117 mm to just 95 for the Triumph. Either way, stick to smoothly surfaced roads or meet potholes at your peril.

The problem is that while the cruiser riding position—buttocks low to the ground, legs outstretched—is fine for making love while seated on a chaise lounge next to the fire, it’s a poor way to straddle a motorcycle. As studies relating to the workplace have shown, we should be standing at desks not seated in chairs. If the standard motorcycle seating position places the feet below the hips—as you’d sit in a well-designed office chair—then the cruiser merely emulates the poor posture of slouching. And what was it your mother said? Sit up straight. Cruiser riders embrace sticking their feet out because their mothers forbade it. It’s nothing more than self-inflicted ass-pounding rebellion.

With the cruiser phenomenon (at last) explained, we’ve redoubled our efforts to be inclusive. And, we admit, sitting on the Suzuki and stretching the legs is impressive if you think of it as the most awe-inspiring toboggan yet built. And with footpegs forced ahead, it allows seats to be dropped. The Suzuki’s is at 705 mm and the Triumph’s just a whisker lower. If you’re reading this while sitting on a toilet, a fair approximation of the Suzuki’s riding position can be attainted if you stick your arms and legs straight out in front of you to make—if you’re viewed in profile—the letter C.

But the letter C, as its shape suggests, catches the wind and pivots the body down hard against the tailbone. At anything close to a quick tempo (120 km/h plus) it becomes a massive workout for the arms and core but only punishment to the lower back and tailbone. We’re taller riders (six feet and up) and rides of any distance on the Suzuki are taxing. How someone five-foot-eight could comfortably reach the pegs is a stretch to comprehend.

Aside from the obvious aesthetic differences—Suzuki’s blingy brightness vs. the Triumph’s murkiness—as soon as the road loosens to anything slacker than a straight line the Triumph blows the Suzuki away like a carpenter blowing sawdust from a workbench. The Triumph’s footpegs are pulled closer to the rider, and allied to slightly more available lean-angle it’s a better machine for making haste. But it isn’t just about maintaining a more sporting pace on a winding road. The biggest difference between the two is the Suzuki’s gargantuan rear wheel with 240-section tire and a wheelbase 95 mm longer than the Triumph’s. If you’ve never ridden a bike with a tire so massive, you can emulate the experience on your bike (with, say, its 180-section rear tire) by dropping the pressure to 10 PSI and strapping a chest of drawers to the luggage rack. This isn’t a failure of Suzuki’s engineers; it’s merely a fact of physics. The Triumph, with a still sizable 200-section rear tire, is nimble in comparison.

But lest you begin to think this a coronation for the Triumph, it’s not so. No motorcycle (except one exclusively for competition) is ever judged—or purchased—based solely by performance. For a cruiser buyer, in particular, performance—in the broadest sense of the word, which includes comfort, function, and utility—is not of pressing concern. That’s not to say that aftermarket seats and windshields can’t improve the riding dynamic, but, at the core, cruisers are motorcycles of compromised function. To the riders who love this kind of motorcycle—and they are legion—it doesn’t matter.

The Triumph appeals to those who would never buy a cruiser. And it appeals to riders migrating to cruisers from other types of motorcycles. A parallel twin, for a machine of such large displacement, is an anomaly, doubly so for a cruiser powerplant. And the Triumph, despite the gothic overtones of its wardrobe, is a cheerful, useful bike. But it’s a cruiser with an English accent.

It must be said that the most successful motorcycle of the two is the M109R. Suzuki, for many years, made hideous cruisers that were neither quirky reinventions (like the Triumph) nor models of the cruiser norm (any Harley-Davidson) but rather oddly conceived bikes that had little to offer except for the Japanese staple of sound engineering. The M109R delivers exactly what is expected of a cruiser; in the way that Angelina Jolie, in her physical prime, was exactly the sum total of aggregated male fantasy. And just as Jolie embodied a savagely curvaceous ideal of perfection that made her more Japanese anime than plausible human, so, too, does the Suzuki seem less a machine than an amalgam of sterile cruiser perfection. And there’s nothing the least bit wrong with that.

Suzuki Boulevard M109R B.O.S.S. Specifications

Model Suzuki Boulevard M109R B.O.S.S.

Price $16,499

Engine Liquid-cooled V-twin

Horsepower (claimed) N/A

Torque (claimed) N/A

Displacement 1,783 cc

Bore and stroke 112 x 90.5 mm

Compression ratio 10.5:1

Fuel delivery Fuel injection

Transmission Five-speed

Suspension Inverted 46 mm cartridge fork; single preload-adjustable pro-link shock

Wheelbase 1,710 mm

Rake/trail N/A

Brakes Dual front discs; single rear disc

Tires 130/70-18 front; 240/40-18 rear

Weight (claimed) 347 kg

Seat height 705 mm

Fuel capacity 19.5 l

Fuel consumption 5.4 l/100 km

Fuel range 361 km

Triumph Thunderbird Nightstorm Specifications

Model Triumph Thunderbird Nightstorm

Price N/A

Engine Liquid-cooled parallel twin

Horsepower (claimed) 98 hp @ 5,200 rpm

Torque (claimed) 115 lb-ft @ 2,950 rpm

Displacement 1,699 cc

Bore and stroke 107.1 x 94.3 mm

Compression ratio 9.7:1

Fuel delivery Fuel injection

Transmission Six-speed

Suspension Showa 47 mm fork; twin preload-adjustable Showa shocks

Wheelbase 1,615 mm

Rake/trail 32º/151 mm

Brakes Dual front 310 mm discs with four-piston calipers; rear 310 mm disc with two-piston caliper

Tires 120/70-19 front; 200/50-17 rear

Weight (claimed) 339 kg

Seat height 700 mm

Fuel capacity 22 l

Fuel consumption 6.1 l/100 km

Fuel range 360 km