Up, up, and away

Ducati burst through the 1,000 cc ceiling with the 1098. With the new Panigale 1299, they just keep on trucking

Few experiences in motorcycling approach the thrill of launching the 1299 Panigale S down the Portimao circuit’s start-finish straight. The Ducati growls out of the preceding long, downhill right-hander in fourth, accelerating hard from over 160 km/h and indicating more than 200 km/h before a nudge of the quick-shifter puts it into fifth as the red-and-white kerb approaches at the outside of the track.

As the Panigale straightens up and thunders onto the straight, there’s just time to short-shift into top and pull my weight forward — but the hard-accelerating Ducati’s front wheel still lifts as the track drops away slightly, and this awesomely powerful and light machine’s handlebars twitch as it rockets past the pits. With my head behind the bubble it’s still picking up speed with the digital speedo indicating over 270 km/h when the 250-metre board insists that I sit up and squeeze the front brake lever for the fast-approaching first turn.

The Panigale is so fast, light, loud and exciting that this mass-produced roadster replicates many of the sensations of testing factory machines at the end-of-season World Superbike test days that were held at this Portuguese circuit a few years ago. Which is slightly ironic, given that the Panigale’s capacity of 1285 cc means that it is ineligible for Superbike racing, so Ducati has had to homologate a separate 1199R for the track.

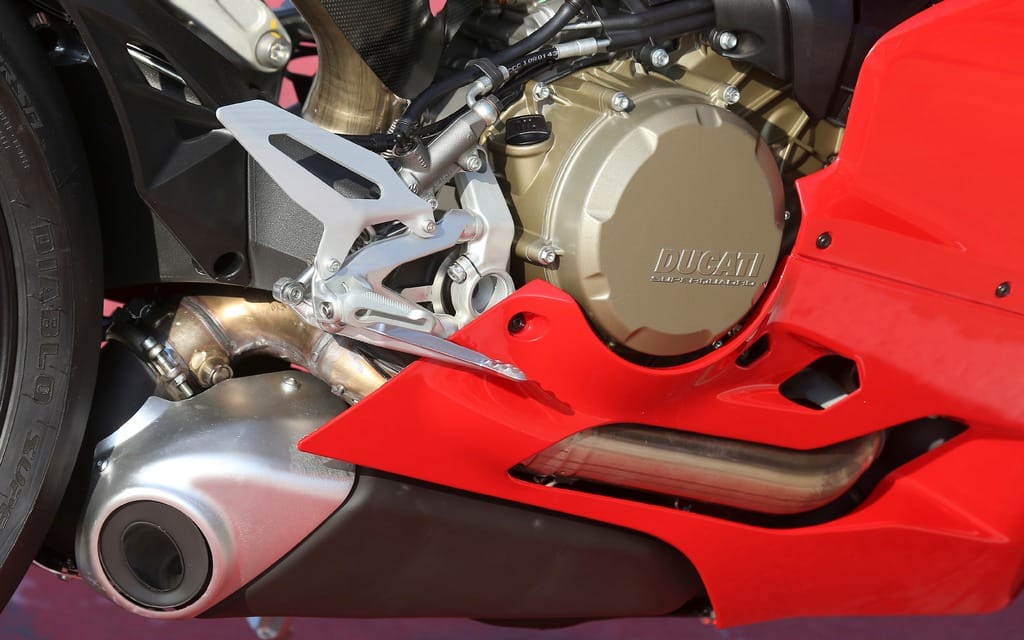

That must be slightly inconvenient, but Ducati’s thinking behind creating the 1299 is clear. In many respects the 1199 Panigale has been a success since its launch three years ago, in showrooms if less so on the track. But the ultra short-stroke “Superquadro” desmo V-twin engine’s fearsome 195 hp was balanced by relatively weak delivery at lower revs that made the bike demanding to ride.

The 1299 Panigale has been created with two main aims in mind. The first is to improve pure performance; in Ducati’s words, to create the world’s “most potent, advanced and exciting superbike.” But the firm also wanted to improve the Panigale as a roadster, by making it more rider-friendly. Hence a bunch of chassis tweaks and electronic refinements, as well as the 87 cc capacity increase from the old model’s 1,198 cc, achieved by enlarging piston diameter from 112 to 116 mm.

That extra capacity allowed not only a 10 hp gain, which takes peak output to no less than a claimed 205 hp at 10,500 rpm, but also an even more substantial increase in torque through much of the range. Dyno curves show the 1299 with a clear advantage over the 1199 everywhere above 4,000 rpm, with a gain of 15 percent or more between 5,000 and 8,000 rpm. And while we’re talking impressive statistics, the Panigale has a claimed wet weight of just 179.5 kg without fuel, giving it an unprecedented power-to-weight ratio for a mass-produced bike, claims Ducati.

One thing the Panigale has never been short of is style. The familiar slinky scarlet lines are subtly reshaped for the 1299, to incorporate headlights in the fairing’s air scoops, and a reshaped rear section with “split” tailpiece. It’s even more visually stunning now than before. The headlights are LEDs in the case of the Panigale S, the more expensive of the two 1299 models, which also comes with forged Marchesini wheels and a carbon-fibre front fender.

More importantly, the S-model replaces the standard 1299’s Marzocchi fork and Sachs shock with Öhlins’s latest Smart EC semi-active suspension. This is linked to the riding modes, of which both models have three: Rain (which cuts horsepower to 120), Sport and Race. The system is composed of a 43 mm diameter NIX30 fork, TTX36 shock, and an electronically adjustable steering damper. The system gives the option of either simple push-button adjustment or what Ducati calls “event controlled” operation, by which all three units are continually fine-tuned automatically, according to parameters including speed, acceleration, lean angle, throttle position and revs.

This in theory boosts comfort as well as performance (because the suspension can be made soft when it’s not required to be stiff), and is not the only way in which the Panigale S has become a little easier to live with. The Ducati’s riding position remains resolutely racy. But its screen is taller by 20 mm, the mirrors are wider and the seat is redesigned to be more comfortable. At 830 mm it’s 5 mm taller, though slim enough to be acceptably low for most riders.

Screen apart, the 1299 felt like a typical Panigale as I reached forward to the clip-ons, took in the details of the Thin Film Transistor digital display (which automatically changes info depending on riding mode, as before, and adds a lean-angle display), and pressed the button to bring the motor to life with a cacophonous, improbably loud sound from the low-slung twin silencers ahead of the rear tyre. The Ducati felt very light in the Portimao pit-lane and it kept that feeling on the track, as it tipped into turns and accelerated out again with a wondrously effortless, neutral steering feel.

The extra grunt was obvious straight away. Even in Sport mode in the first session the Ducati felt super strong, punching out of turns from as low as 6,000 rpm with an urgency that the 1199 just couldn’t have matched, and taking several bends a gear higher than the peakier smaller engine would have demanded. This was useful when relearning the track and would be even more of a boost on the road, where the 1299 would be quicker with fewer gear changes.

Not that those were remotely a problem, thanks partly to the new quick-shifter that operates on both up- and down-changes, and which worked flawlessly. As with BMW’s S1000RR, I found the auto-blipper function really useful in freeing my mind to concentrate on more crucial things like tyre grip while braking hard and charging into bends. Another handy addition is the wheelie control, which did exactly what it said by gently cutting in to keep the front wheel near the ground and the bike driving forward.

And boy, was that useful as the ultra-light and torquey Panigale ripped out of the turns and charged over Portimao’s crests, and even as it hammered onto that long pit straight and managed to pick up its front wheel in fifth gear, in a way that I thought only factory racebikes could manage. It’s adjustable through eight settings and worked so smoothly, allowing more or less wheelie, that it was difficult to be sure exactly when it was cutting in.

But I was glad to have it, as I was to have the revamped and similarly adjustable traction control system, either of which can be adjusted while riding via the pair of thumb/finger buttons below the left clip-on. You have to choose which function to adjust on the move before setting off, and I found the change slightly erratic, but I suspect I’d have got the hang of it with a little more riding time. The latest systems are so sophisticated that it hardly seems possible that it was only six years ago that Ducati’s 1198S, also launched at Portimao, became the first mass-produced bike with traction control.

Chassis performance is also significantly updated, by electronic and conventional means. The Panigale chassis remains based on a monocoque design that uses the engine as a structural member and adds an aluminum front section that doubles as the airbox, contributing to the bike’s light weight. The 1299 has a half-degree steeper steering geometry (at 24 degrees), and follows the race-oriented 1199 Panigale R in having a 4 mm lower pivot for the single-sided swing-arm, for improved grip under acceleration.

The Ducati steered brilliantly, its light weight and sharp geometry allowing quick changes of direction with great precision. I was really impressed by the Öhlins set-up, which firmed up the front end to allow fearsomely hard braking, yet was compliant and gave excellent feedback once the stopper was eased off into a turn. The front end, in particular, felt fantastically planted and controllable, doubtless helped by track-ready Pirelli Supercorsa SC tyres that are even stickier than the Supercorsa SPs that Ducati fits as standard.

The system gives the option of turning off the event-based control to leave conventional electronically adjustable suspension, but when it works as well as this the semi-active system makes plenty of sense. That said, the Panigale took some setting up, and initially shook its head on the way out of a few turns, including that last high-speed run onto the pit straight.

In event-based mode the Smart EC gives five options for fork, shock, and steering damper, with each unit’s default middle setting flanked by harder, hardest, softer and softest; and all the settings getting progressively stiffer as you go from Wet mode through Sport to Race. Being tall and quite heavy, I stiffened all three from standard to the harder setting in Race mode, which helped but didn’t cure the wobbles. It was only when I firmed-up front and rear to the hardest setting for my last session that the Ducati was miraculously calmed, and barely twitched. Ideally there would be more settings, some stiffer still, to increase the options for large riders in particular.

There was no such caveat with the braking system, which was not just good but surely the best yet seen on a streetbike. The Brembo M50 Monobloc calipers, 330 mm rotors and Bosch’s latest 9.1MP ABS system gave a stunning blend of power and controllability. And the Panigale system also incorporates an even more refined version of Bosch’s brilliant cornering ABS system.

When I finally plucked up the courage to squeeze the front lever while cranked way over in a second-gear left-hander, the Ducati simply stood up slightly before resuming its course. I didn’t hear the tyre squeak, so wasn’t 100 percent sure that it had skidded. But I wouldn’t have fancied pulling the same stunt on any other sport bike I’ve ridden, and the system looks like boosting superbike stopping ability to new heights. By default the cornering ABS doesn’t work in Race mode, but you can choose to activate it with a button-press or two.

Cornering ABS will be of more use on the road than on the track, especially in bad weather, and the Panigale’s other rider-friendly features will also be beneficial. Its screen is substantially taller and easier to shelter behind; the mirrors seem to work; even the footrests are machined to negate the common complaint that Panigale pegs are slippery. Only the sidestand adds a slightly discordant note, being too tucked-in to be easily used.

The 1299 Panigale is a notably superior streetbike to its 1199 predecessor, and equally importantly it will surely prove significantly quicker on the track. Those power and weight statistics are mighty impressive, and the Ducati feels every bit as fast as they suggest it should. More importantly still, its state-of-the-art electronics will help riders of all levels maximize its, and their, potential.

One or two of the Panigale’s rivals are probably more accommodating, but a perfectly dialled-in 1299 might well prove the quickest of a stunningly quick bunch. When you add to that its drop-dead looks, captivating V-twin character, improbably belligerent exhaust note and even its newfound rider-friendliness, the result is something truly special. For me it’s Ducati’s best superbike since the 916.