Neil Graham, in a Canadian exclusive, is one of only a handful of worldwide journalists to ride MV Agusta’s new F3. And he can’t wait to tell you the news.

I exit the chicane, open the throttle to the stop, and select the next cog in the gearbox when the tachometer hits 13,500 rpm. I’m doing my best to keep former AMA racer Eric Bostrom in my sights when I enter a long right-hander topped out in fourth gear. It is one of those corners that requires complete commitment. You need to feel good about the bike beneath you, the fit of your underwear, and the adhesion of your tires. It is only when I’m gaining on Bostrom that I become alarmed — my knee is on the ground at an ungodly speed and the ambient temperature, displayed each time I pass the sign on the front straightaway, is 3.5 degrees. But the tires stick, the rider doesn’t do anything rash, and Bostrom, as I knew he eventually would, picks up his pace and falls from my grasp.

MV’s teaser campaign for the F3 (of leaked photographs and slyly shot videos) was preceded by a long period of rumour and speculation, so I feel obliged to cut short the usual teasing and sly preamble to this tale and cut to the chase: MV has made a stunning little machine. So good, in fact, that it’s arguably the first MV since the resurrection of the nameplate worth buying for its function alone, and not just because of the accumulated lore of Agostini and Hailwood and good old Count Agusta himself. In other words, it’s not just a fashion accessory — it’s a very good motorcycle.

A three-cylinder sporting motorcycle of 675 cc displacement seems, at first glance, to be a shameless pilfering of a formula devised by Triumph for its 675 Daytona. And it is. Though in MV’s defense, they raced triples back in the day, so the three-cylinder motorcycle is as justifiable-by-heritage to them as it is to Triumph. But that’s beside the point. Triumph’s Daytona is a sublime sporting motorcycle, so kudos to MV for recognizing the finest among its peers and setting forth on their own interpretation on the theme.

On pit road at the Paul Ricard circuit (once home to the Bol d’Or endurance race) a group of predominantly European hacks (along with American Bostrom and Canadian Graham) stomps feet and blows into hands. It is a very un-south-of-France-ish three degrees below zero when we first arrive in the morning. Snow is up in the mountains, but more disconcertingly, ice is on the back straightaway where the racetrack is shadowed. In broken English an instructor at the circuit claims that pylons will prevent us from finding the ice. I hope he’s right. But then I’m distracted by a sound — or rather, The Sound.

The first-fired F3 puffs exhaust from its trio of pipes like a steam engine and settles into a fast idle. Thirty seconds later its throttle is blipped. What a sound — raspy, growling, mechanically engaging, a little like the V6 in the 246 Dino I trailed on the highway last summer. I’m relieved, because if the sound from those pipes had been like the note from my father’s V6 Chevy Lumina it would have been unforgivable. This is an MV, after all, and these things matter. Adrian Morton, the bike’s designer, would surely agree.

Morton, a barrel-chested Englishman who looks like a cross between a soccer hooligan and a security guard, had the unenviable task of designing the F3. I say unenviable because although designing Italian motorcycles should be a dream gig for a designer, following in the footsteps of Massimo Tamburini is not. Tamburini designed Ducati’s 916 and MV’s F4 and then retired to a life of producing olive oil or balsamic vinaigrette or whatever else cultured men of the arts do in Italy when their working days are done. The problem is that Tamburini worked like an Old Master — it took five years, a cadre of indentured servants, and a naked goddess fanning him with a palm leaf for him to make each masterwork. Morton, on the other hand, had a year to come up with the F3, and if he wanted a cup of coffee, well, he could just get it himself from the cafeteria.

In a recession-strapped world one year must equate to five, because Morton’s F3 is a mini-masterwork. It’s small, almost two-stroke 250 small, and there isn’t an angle from which it appears awkward. The right rear three-quarter angle is its most distinctive, however, and the 30 prospective buyers in Canada alone that have plunked down deposits have done so, I’m guessing, based on that view alone. (The F3 is due to arrive in dealerships in July, though supplies will, as the saying goes, be limited.) And while it may be trite to focus on something as insignificant as the colour of a motorcycle, I encourage buyers to ignore the all white or the two-tone black and grey versions. In the words of designer Morton, “It really has to be red and silver, doesn’t it?”

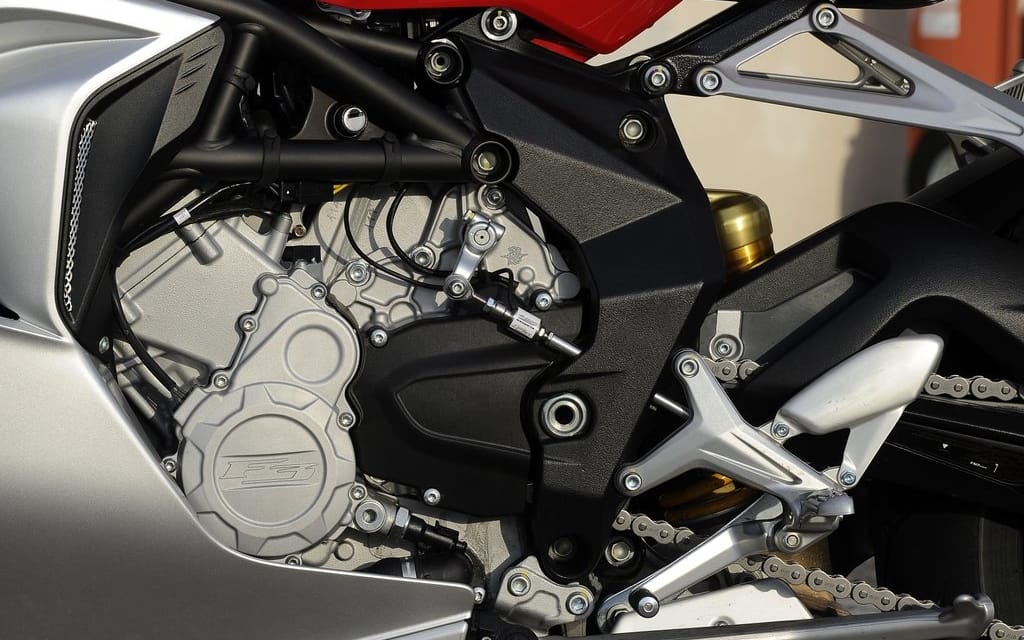

MV, for the F3, claims 126 crankshaft-measured horsepower, a wheelbase of 1,380 mm, and a dry weight of 173 kg. That makes it, respectively, in the ballpark power-wise, the shortest-wheelbase sportbike, and way lighter than your Gold Wing. Surprisingly, it also fits six-footers like me — I may look like a giant sitting on it, but I can tuck in behind the windscreen, and side-to-side transitions to allow for aggressive cornering are easily accommodated. Given its dimensions, it’s unsurprising that the mantra during development was compactness. But the F3’s agility isn’t only from lightness and component packaging. It’s the first non-MotoGP bike to use a counter-rotating crankshaft, which counters the gyroscopic effect of the wheels’ rotation and makes it as nimble as a unicycle.

A first for the middleweight sportbike class is three preset (plus one tunable) engine maps to tailor power delivery along with eight-position traction control. Due to limited testing time I leave the power delivery on full but tweak the traction control for each session. In its most invasive setting, traction control reins in tire slipping, and at its least invasive, power slides can be coaxed while exiting tight corners. And still on the topic of tight corners, it’s while exiting the two first-gear bends on the circuit that the abruptness of the low-speed fueling can be sensed. I try using second gear (it’s too tall) but ultimately find a compromise by running a smoother line and by feeding throttle in more progressively. Another glitch marring a perfect score (and agreed upon by journalists over lunch) is the gearbox’s occasional reluctance to accept aggressive upshifts. (Buyers can bypass the problem by fitting MV’s excellent Electronically Assisted Shift option, which allows full-throttle clutchless upshifts. Half of the bikes at the launch are so equipped, and once tried, it becomes as indispensable as air in the tires.)

I confess to finding the F3 a beguiling combination of a classic raw-edged European sportbike crossed with the unflappable competence of a Japanese 600. The charismatic three-cylinder mill is reminiscent of Triumph’s Daytona (though the MV’s power delivery seems less vigorous than the Triumph’s down low in the rev range and more stirring up top) but the agility and confidence-inspiring comportment of the chassis is a hallmark of Japanese 600s. Add all this up (to a total of $14,495) and you’re left with a machine that will certainly be one of this year’s — or any year’s — most significant motorcycles.