Sometimes only a half-dozen will do — BMW sinks the languid LT and resurfaces with a pair of sixes.

I’ll cut straight to the punch line: this is not a BMW Gold Wing. If you’re a devotee of toy runs, have a CB antenna whipping from the top case of your Honda Gold Wing and were hoping that BMW was going to out-Wing-the-Wing, you’re out of luck. The GT and GTL aren’t really for you. But if a big tourer with a six-cylinder engine isn’t aiming for Gold Wing territory, then what kind of a bike, exactly, do you end up with?

When BMW announced it was going to make a six-cylinder motorcycle most believed — I certainly did — that their goal was to thump the Gold Wing. The Wing is certainly vulnerable. It hasn’t been meaningfully updated in years, and BMW, with its odd-looking but effective R1200RT, has the most effective fairing in motorcycling. But instead of plunking the 1,649 cc inline six shared by the GT and GTL into RT-style bodywork, BMW had something else in mind, and it was more than just an updating of its outdated K1200LT.

“Initially we considered making a big, RT-style tourer,” said BMW designer David Robb, “but we didn’t think the time was right.” He may as well have said the zeitgeist, too. BMW, in attempting to inhabit a future more up tempo than its past, wants to make its bikes more like its cars: high-performance machines that stress engineering prowess and downplay nonsensical quirkiness (bon voyage, three-button turn signals, you shall not be missed).

Let’s start with the best bits — the six is a great sounding engine. BMW isn’t known for motorcycles with stirring exhaust notes (we’ll exempt the S1000RR, but while aurally satisfying an inline four, as the default engine configuration of the last 40 years, is all-too familiar) but the six possesses a lovely mechanical song and exhaust note — rich and fruity at idle with a spine tingling urgency at its 8,500 rpm redline. A peculiarity is that the $24,100 GT (immediately distinguishable by its lack of top case, though it has other, more subtle differences from the GTL) has a louder exhaust note than the $29,225 GTL. The idea, methinks, is that the GT is a solo-touring mount while the GTL, with its top-mounted armoire and backrest, will host a passenger more often than not. And passengers, especially recalcitrant ones, just don’t dig the sound of an engine in the way that the person at the controls does. At least that’s been my experience.

In designing the six, engineers had one big thing in their favour and one big strike against. The good is that an inline six-cylinder engine has perfect primary balance; power-sapping and space-consuming balance shafts are unnecessary. The bad — apparent to anyone who has ever taken the six beer bottles from a six-pack and lined them up on the table in a row — is width. BMW’s answer to the packaging problem was to keep the bore, at 72 mm, moderate (stroke is 67.5 mm), and then jam the cylinders as close together as possible — a scant 5 mm apart. Presumably they didn’t forget to mine passageways for coolant, and each cylinder has a pair of intake and a pair of exhaust valves.

Enthusiasts who corner me in pubs sometimes ask, if the conversation swings around to the size of contemporary motorcycles (and after they’ve told me how much they love their V-Strom, wife, and kids, in that order), what it’s like to ride really large touring machines. The answer is simple, if difficult to put succinctly. Any motorcycle is straightforward to ride (once you have sufficient experience) once it’s rolling. Where the size of a Gold Wing or BMW’s old LT can intimidate is at walking speeds, before the gyroscopic effect of the wheels stabilizes the motorcycle. A large bike barely moving imparts the unease of wrestling a queen-size mattress single-handedly down a flight of stairs. But the GT and GTL, despite claimed fully fuelled weights of 703 and 767 pounds, respectively, are a step forward — once you’re moving balance is easy and steering light and intuitive.

And once you’re moving, you’ll really be moving. I begin my day in the Georgia hills aboard the top-case-equipped GTL. Initial reactions when you first straddle a new motorcycle create significant — though not always conclusive — impressions. My first thought is of remarkable mechanical sophistication. Fuelling, shifting, and throttle control are precise and forgiving. And it’s fast. My fear of the Georgian constabulary (I’m more terrified of cops now than when I was a teenager) limits my top speed burst to 160 km/h, but with a claimed 160 crankshaft horsepower (at 7,750 rpm) and 129 lb-ft of torque (at 5,250 rpm) there is lots more gumption if you’re willing to risk prison. Supposedly 70 percent of its torque is available from a lowly 1,500 rpm, and it’s a believable claim, as there is no discernable powerband — just twist and go.

My second thought is that a motorcycle with a frontal area this large should direct the wind past the rider more quietly than the GTL does. It isn’t noisy, but neither is it the RT, just as David Robb stated. I move the electric windscreen though its full arc and am not able to find a sweet spot — eyes just peering over the screen and eerie silence all around — in the way that I can with the RT screen. The screen is its quietest when I’m looking through the top few inches, but buffeting along the Georgia turnpike flexes the screen and distorts the view, and I lower it for piece of mind. The GTL, despite its size and weight, was clearly designed to be a sporting motorcycle, and despite over-excited wags inventing a new category for it to inhabit all by its lonesome, it slots comfortably into the luxury end of the preexisting sport-touring category. That’s not a criticism; it’s just a fact.

What the six is hoping to stir, I believe, is a groundswell of desire for its engine, both for the performance of it and, more significantly, for its aura. Pieterde Waal, the V.P. of Motorrad U.S.A., said, of the bike’s development, “It had to be a six. We had to find a reason for enthusiasts, even if they couldn’t afford the bike, to want it.” It’s a bullish statement for a manufacturer to make, and in a country wracked by the home foreclosure disaster, telling: maybe the only way to move big and expensive motorcycles off showroom floors is to make people fatally attracted to them.

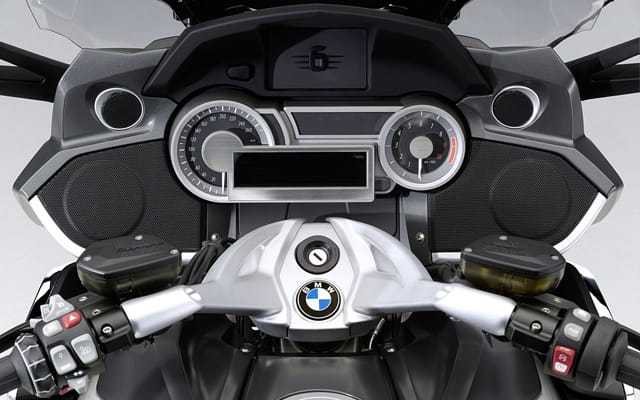

After a morning aboard the GTL I began to understand the allure of a straight six: Jaguar and BMW car guys praise them as vociferously as Italian car nuts praise the V-12, and the something about them is a mixture of pedigree, sound, and uncanny smoothness. The engine aside, the GTL is a fine-handling, light-footed machine. A pleasant surprise is the cockpit, which, for a big-rig, is unusually spare. Compared to the Gold Wing’s baffling array of buttons and switches, the GTL (and GT) have a rotary dial just inboard of the left handgrip that gives access to the onboard computer. With information displayed on the screen just above the gauges and below the windshield, to make a selection you cock the dial sideways to select. It’s a clever system, and given the plethora of information to be relayed, straightforward to understand.

As is BMW’s tradition with its big touring machines, the standard feature list is long and options come individually and in bundled packages. Standard on the GTL is heated grips, Bluetooth capability, Xenon headlights, seat heating, ABS, and panniers with top case. Options include traction control, tire pressure monitoring, electronic suspension adjustment, central locking for the luggage, an alarm system and LED fog lights. The most intriguing of the options is an adaptive Xenon headlight system. Employing a lean angle sensor of the type developed for the traction control system on the S1000RR superbike, the light points in the direction of the turn. It works like this: the Xenon light shines into a mirror that receives information from the lean angle sensor to determine how tight the corner is. The mirror then pivots to shine the light into the corner as opposed to pointing straight into the trees. On a night ride the system certainly proves itself; intentionally weaving while riding a straight section of road makes the light swing drowsily to and fro, very nearly emulating the sensation of stumbling through the woods at midnight on a camping trip while searching for the outhouse. We didn’t have the opportunity to test pivoting vs. non-pivoting Xenon lighting, and though you’re certainly aware of the light creeping around the corner ahead of you, what impresses most is simply the sheer brightness of the Xenon bulb: the rocks and underbrush of a Georgia ditch bleach white under the ruthless intensity of the bulb.

After lunch at a winery that involved ingesting no beverage stronger than water with carbonation, I hit the road on the GT. The stimulating purr from the louder-than-the-GTL muffler helped to chase my craving for a nap, and, as before lunch, we went in search of twisty roads. It can be startling how minor changes can significantly change the personality of a motorcycle, and the GT, despite being much the same bike as the GTL, was altogether a more satisfying motorcycle for me. The GT has higher footpegs and a higher seat height than the GTL that seemed to integrate me more successfully into the motorcycle. The GTL has a standard seat that sits at 29.5 inches, which is exchangeable at no cost for an optional seat of 30.7 inches. The GT’s standard seat is two-position adjustable (31.9/32.7 inches) but it can be exchanged for one even lower, at 30.7 inches. Whether or not the higher perch placed me optimally behind the fairing or if the slight dip in the top edge of the GT’s windshield (the GTL’s screen is slightly raised) better managed airflow it’s hard to definitively state, but the GT was a quieter place to watch the world unfold. Perhaps quieter is the wrong word. I wish I could say with surety that the 60-or-so fewer pounds liberated the GT but I don’t think that would be true. No, what got my blood flowing was that exhaust note, which likely sounded louder than the GTL’s in part (only in part because the can is slightly louder) because the fairing produced less distracting wind noise. When you’re happy on a motorcycle everything falls into your lap: the tires stick better, your eyes look further through the corner, and the butt is less prone to drifting off to sleep.

The GT, unsurprisingly, since it’s significantly less money than the GTL, has a shorter list of standard equipment, but the stuff you want most is on the list. Heated grips and seat are there, as are ABS and the (non-swiveling) Xenon headlight. I don’t listen to music when I ride (listen to the engine, silly) and I have no interest in wiring myself for intercoms and cell phones. The one option I would insist on is ESA 11, which is electronic suspension adjustment. It allows on-the-fly adjustment through various modes from comfort to sport and even compensates for passenger and pannier weight. It’s $925 on its own or in a package for $1,100 bundled with traction control and the adaptive headlight. Take the package, please.

My personal motorcycle aesthetic draws me to machines that are simple and lean, so when David Robb speaks of “floating the head” of the fairing to minimize bulk, I understand his point even if I can’t quite get down on my knees to pray at the church of Robb. To my eye both bikes have a lot of bulk up high and dwarf their wheels to the degree that they look like castors on a fridge. I don’t think that big touring bikes can be beautiful, but not every machine need fire the loins on looks alone. And besides, if you can’t make a machine look like Grace Kelly, giving it a voice like Nina Simone more than amply compensates.