Or: How we learned to stop worrying and love the Boss Hoss (and its little friend the Rocket III)

They’re drunk on power, Graham and Wachtendorf. It is six degrees Celsius at 6:30 on a mid-week Florida morning and fingers have long ago lost feeling. Laughter from inside helmets has a maniacal edge and fogs the visor blind. But that’s fine, because looking where you’re going doesn’t matter on motorcycles like the Boss Hoss and Rocket III. They slow down on the interstate to 50 mph to thaw the fingers just enough to regain the grip required to uncork the 585 (combined) horsepower jammed into their groins. Fear and anticipation in perfect balance negate each other, and in the snap of the throttle eyes water and the world wrinkles and they don’t give a good goddamn if that pick-up veers into their lane. They’re feeling so good that they don’t care what might happen. But I do. I’m sitting on the back of the Boss Hoss.

Later, calmed, they regret their outburst. We all might have died. Fingers still hurt from the cold. Hips have a prison-cell ache and they walk like plastic cavalrymen yanked off plastic horses. Neil walks like this anyway. But Uwe is in pain. They are arguing about the note from the accessory (loud!) exhaust on the Rocket III. Neil says it’s the worst sounding motorcycle he’s ever heard, a nasty fusion of food processor and outboard motor. Uwe says it sounds really, really great. (He says “really” twice to piss Neil off. It works.) There is silence between them. They do not try to disguise their disgust for each other. Neil threatens Uwe by telling him that he can be the editor of the magazine. That shuts him up.

They have spent the last 10 days together in a Florida hotel room, like fugitives on the lam from Arkansas or Texas. This is not what Uwe thought working for a motorcycle magazine would be like. He is having doubts. He is not having fun. He feels better when he remembers that his training as an electrician could get him another job. But Neil, without other useful skills, is stuck. And he knows it. We go for another ride and end the awkwardness.

Neil has had some experience with the Boss Hoss. When he was a contributor to English motorcycle magazine Bike he went to Memphis, Tennessee, and rode one for a week. Bike refused the story because of the vulgarity of its content. I’ve read the piece, and it involved a lot of drinking and strip clubs. But I did learn that if you want to park a motorcycle behind the velvet rope at a strip club then the only motorcycle to own is the Boss Hoss. It commands respect like a perfect pair of fake tits.

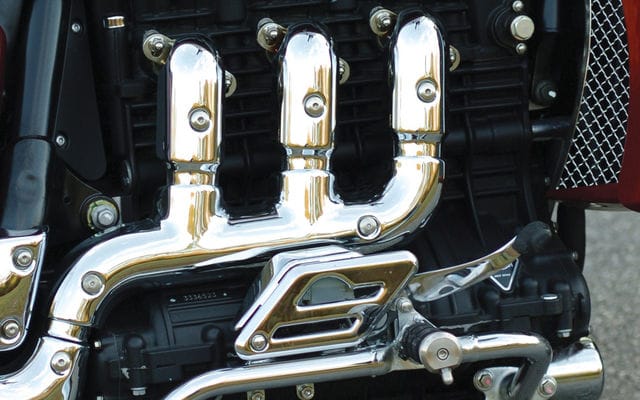

When we picked up the Rocket III it seemed like a grotesquely huge motorcycle right up to the point when we pulled up beside the Boss Hoss. The Triumph may have 2,294 cc spread out over three cylinders, but the Boss Hoss’s V8 is a whopping 5,965 cc. As the lads listen to the briefing from the Boss Hoss man, Uwe is already backing toward the Rocket III—he’s afraid of the Boss Hoss. Neil recognizes what Uwe is doing and quickly tosses him the keys to the Boss Hoss. Uwe jumps out of the way and the keys fall to the ground.

The major problem with the Boss Hoss is not the riding of the thing—that’s pretty easy—it’s the heat generated from the engine. Chilly Florida temperatures do not make this an issue for our testers, but, as Neil wrote in his stillborn Bike piece, “Riding a Boss Hoss on a hot southern day is like flipping the hood up on a Chevy Caprice after a long drive and sitting on the air cleaner.” I’m glad that I wasn’t with him in Memphis—for any number of reasons—but I just can’t take that kind of heat.

But this new Boss Hoss is a different animal than the one Neil rode 10 years ago. Where Boss Hoss used to employ the iron-block 350 cubic inch Chevrolet V8 that powered generations of cop cars and pick-ups, the LS3 uses an all-aluminum 445 horsepower V8 from the Corvette that beats the old engine by 100 horsepower. The new motor’s greatest asset, according to Neil, is its ability to frighten. “When you opened the throttle on the old engine it didn’t terrify as much as you might have thought for a 355 horsepower motorcycle. It was less thrilling than a Hayabusa.”

But this new V8 has changed everything. On cool pavement with cold tires it is impossible to open the throttle fully. Acceleration is so immediate that the world lands in your lap. The transmission is a two-speed semi-automatic shifted by foot. Low is “good to 100 mph” according to the Boss Hoss man. Without a clutch, it’s as easy to ride as a twist-and-go scooter: as soon as you’re moving it’s stable, and you can ride it as slowly as a trials bike.

Just don’t confuse stability with agility. You can’t discuss Boss Hoss handling in the way that you would any other motorcycle. Like a shopping cart, it changes direction when you ask it to, but corners aren’t the point—corners are just impediments to finding the next straightaway.

When it is Uwe’s turn to ride the Boss Hoss his brow has more than the usual number of furrows. He has been scared by the story that he heard of the man on the Boss Hoss demo ride. The man, who has since recovered from his injuries, slipped the bike into neutral so he could blip the throttle and hear the bellow of the horsepower. But the torque reaction of the engine was so great that the bike flipped onto its side and crushed him—at a dead stop. Uwe, himself, has a startling moment when, on the highway, he shifts from low to high and the bike shakes its head violently. But that’s what the Boss Hoss does. It’s the sort of thing that happens on a motorcycle with twice the power of a Moto-GP bike, and if you can’t handle it go ride something small—like the Rocket III.

The Rocket III, the reigning displacement champion of what we might charitably call conventional motorcycles, is bland next to the Boss Hoss. But the blandness stems from the fact that it does everything that a motorcycle is supposed to do. It stops, accelerates, and corners like a proper motorcycle. It may look like a cruiser, but it works better than a cruiser. The only drawback, so say the lads, is an excessively heavy throttle that feels like you’re pulling on a rope tied to a cinderblock. Other than that the only real criticism is excessive jacking from the shaft drive, but even that’s kind of fun, as popping up into the air while you’re being shot forward is just acceleration in another direction.

Then there is the issue of sound, where the Rocket III is simultaneously the single worst/best sounding machine in motorcycling according to its testers. (It must be said that the cure—should you find the accessory exhaust obnoxious—is simple: just refit the inoffensive stock system.) But even Uwe admits that if you ignore volume of sound and concentrate on sound quality, the Boss Hoss is the victor. Surprisingly, given the truncated exhaust system (compared to the lengthy system the engine would have when mounted in a car—its normal environment) it is surprisingly quiet. Mechanical noise is minimal, too, but roll on the throttle and you’re wrapped around a piece of Americana—the V8 engine—as powerful as it is charismatic. But the Boss Hoss’s greatest strength—its only strength—is also a crippling liability.

Born out of frustration with underpowered Harleys, the idea of jamming a V8 in a bike is as ludicrous as strapping a rocket to your back and donning roller skates. And yet it works. Better than it has a right to. You could ride the Boss Hoss like a normal motorcycle, but at $65,900 it would be a -colossal waste of money—if you’re not scared shitless you’re riding it incorrectly. We see a man in a parking lot climbing off a Boss Hoss trike, and we pounce. “Sir, excuse me, but don’t your, uh, legs and hips hurt from straddling that engine?” “No,” he says, but then he has a prosthetic leg. Oops.

But straddling a V8 is not the only drawback. With the exception of the reverence that you receive from bouncers at strip clubs, the rest of the time you just feel like a jerk: you’re riding a motorcycle with a car engine, what are you trying to hide? What are you compensating for? Lost love? Potbelly? Thinning hair? (Neil) No hair? (Uwe). And why do they paint it in senior-citizen motorhome colours? It should be flat black, hand sprayed in a windstorm. It should intimidate and not be the colour of tampon packaging.

Is there anything left to say? The Triumph is the better deal; at only $16,899 you could buy four of them for the cost of the Boss Hoss. But what fun is practicality? And the Boss Hoss, if you tire of it, could donate its engine to power your car or a log splitter. The Triumph, in an absurd way, is let down by its usefulness. But we can’t hold that against it. On the other hand, we can hold everything against the Boss Hoss. But I implore you, dismissive reader, with your love of sportbikes or dirt bikes or any other kind of bike that works, to resist what happens when the throttle is opened on this monstrosity. You would love it too. Really, you would.

Boss Hoss speedometer jumps to the north end of its dial very quickly. Wimpy blue and white paint is a letdown.

Some perspective: Rocket III is the displacement king of conventional motorcycles—and it’s dwarfed by the Boss Hoss.

During a stop for photography, I looked over the headings on my Cycle Canada test sheet and realized the futility of applying a normal test regimen to these motorcycles. A brazen celebration of obesity and overabundance, the Boss Hoss and Rocket III are raised middle fingers to a world concerned with moderation and practicality. With both machines—but especially the Boss Hoss—performance is measured not in numbers but in entertainment value. Some manufacturers claim to style their motorcycles after muscle cars, but the Rocket actually is a muscle car. From the NASCAR roar to the wild shaft jacking the Rocket ingratiates with its antisocial persona—it turns out to be the motorcycle I never knew I wanted. But just when I thought it had slam-dunked all comers I met the Boss Hoss. Of everything two-wheeled that I’ve ridden nothing prepared me for this level of insanity. Nothing required such a judicious throttle hand or wide spread of the legs. That law-abiding citizens will never even use second gear only adds to the fun.

—Uwe Wachtendorf

This is the Boss Hoss that I’ve been waiting for. It is the machine that I wanted the one 10 years ago to be: frightening. There is nothing more satisfying than to have perceptions satisfied. We want Ducatis to be uncomfortable, Hondas to be a bit dull, Harleys to be out of step with the technology of the times and a Boss Hoss to scare us to death. But to own a Boss Hoss would be to wake up every morning and look over and have the regret that comes when you realize that you married the tough looking blonde that you met in Vegas while you were working through the misery of your divorce. There is nothing wrong with a dalliance to distract, but did you have to marry her? How did that happen? The lesson? If you get a chance to ride the Boss Hoss take it. Just don’t take it home. One more thing: the Rocket III really does sound dreadful with the accessory exhaust. At least I think so. And until I’m fired I get the last word.

—Neil Graham