It connects our largest city to the nation’s capital. So why is Highway 7 such a desolate stretch of road?

Only blackness, nothing can be seen, but slowly the room appears as eyes adjust from midday sun. A television lies face down and pressed to its back is a section of collapsed ceiling. Fallen insulation coats the room in black drifts of snow, half burying an overturned chair and giving a sofa the humped-back of a stooped cow. Pulling back branches allows a breeze to slip through shards of glass and disturb the room, sending insulation running down the front of the reception desk past letters that read HAP Y VAC TI N. Each year the motel sinks lower, driven to its knees by the elements, flattened by decay.

Highway 7 was the border when I was a kid, not the one between this country and America. North of 7 my parents said, as a way to explain why, at the truck stop in Actinolite, a bear paced back and forth back and forth in a too-small pen past kids bouncing on chain-link fence. North of 7 I said to a friend when we saw a man crawling on all fours across the road after midnight on the way to the lake. In the south police would be called; we steered around and kept going.

At first I’m not sure it’s the same place, but on the wall of the restaurant I see photographs of children clustered around a bear cage. A note beneath the photograph says that his name was Teddy. Teddy Bear. Dead at age 31. Just over the hill, the waitress says, that’s where his pen was. Grass is reclaiming the pad where the pen stood, but the flat spot on the hill is unmistakable. It is smaller than I remembered, and I remembered the cage as small. Before I leave two women pull into the parking lot. The driver leans forward to see past the passenger to the restaurant. They talk for a moment and drive on.

Along the road it’s hard to tell where people are living and where they’ve moved on. A car parked beside a house sits with its door open, ready for a driver, but as I look for passengers I see the three-inch tree growing between body and bumper. Between Peterborough and Perth five cars sit on jacks with wheels removed, the owner interrupted by a phone call or by dinner, but each is next to a building missing doors or windows. They’ve been sitting for years. A Mercedes pulls into a gas station that now sells only firewood to cottagers, and the driver asks the woman in the lawn chair how far to the next station. She can’t say. They ask about the food in the restaurant next door. It’s all closed up, the woman says.

At a party in high school, I gave up trying to unlock the bathroom door when someone inside giggled, and walked to the pasture beside the farmhouse. A pickup pulled into the lane, six men in the bed but the driver alone in the cab. Once they were gone I looked in the window. On the floor a half full case of whiskey, on the dash six empty bottles. Lying across the seat a chainsaw so long that it must have had to rest on the driver’s lap. Later, inside, I watched the driver hand his keys to someone going to retrieve another bottle. Don’t touch my chainsaw, he said, dangling his keys for emphasis. I’d never seen these people; I asked the driver where they were from. He didn’t look at me when he spoke. Back of 7, you wouldn’t know the place.

Kaladar sits at the intersection of 7 and 41. To the south is Napanee, to the north Eganville and, farther on, close to the Quebec border, Renfrew. I walk to the front door of the Kaladar Motel. A dog is barking but the snap of a heavy chain reassures. I knock on the office door but there is no answer. I look inside. The room is now a storeroom for hubcaps from cars long rotted off the roads. At the house next door a dark skinned man answers but doesn’t offer a name. He’s been here for 17 years, he says, and can find any hubcap I need. I can’t tell if in his soft accent I hear Spanish or Middle Eastern inflections. He invites me to look around and offers a glass of water. In one of the motel’s rooms I cut my arm on the serrated edge of a hubcap, then startle myself when I catch my reflection in the bathroom mirror. The toilet is in pieces, a ceiling fan sits in the sink and the bathtub overflows hubcaps.

At the Fall River Bar and Grill, in Maberly, I sip a beer as a man enters and orders two slices of dry toast and a beer. He doesn’t sit. He looks familiar. We talk, and discover a mutual friend I’ve not seen in years. The friend was an alcoholic, his business failed, his house taken away. His wife left with their twin sons. Then he moved back to England to live with his younger sister, the man tells me. It is an awkward conversation to have over a drink on a weekday afternoon, and when the server asks if we’d like another we decline. The Ottawa Citizen newspaper called the Fall River restaurant the greenest in Canada; owners Paul and Michel Zammit cool the building with water from the artesian well, heat it with oil from the kitchen and use locally grown ingredients. Paul Zammit, a motorcycle mechanic by trade, claims that they chose the location because there was nothing else around, and they’ve succeeded where the greasy diners and French fry trucks have failed.

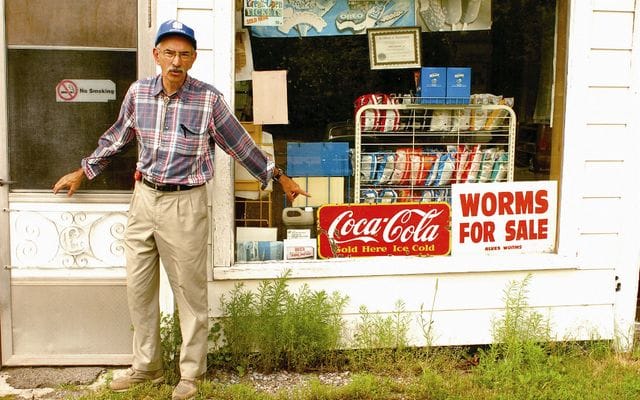

A man walks from the door of the gas station and sits in a chair underneath the stooped limbs of a pine tree. I can only see him from the chest down. As I approach the door his hands stop tapping against the armrests and freeze midair. I pause. After another step his hands grip the armrests and he rises. We meet at the door and Howard Gibbs insists I enter first. Artifacts at his station chart the passing of the years. Headlights from six-decade-old cars peek from behind shrubs, signs advertise beverages with unfamiliar names, a wood stove sits in the middle of the floor. Hand hewn beams in the service bays look down on tools undisturbed for decades. Howard pulls from the shelf a plaque from Imperial Oil given to his father on the 50th anniversary of the station. Tacked to it are two black and white photographs of his father tightening, or loosening, lug nuts on the wheel of a logging truck. One is a view from behind as he bends over, his face hidden, in the second he has become aware of the photographer and looks back over his shoulder. He could be smiling, but with his thick moustache it’s difficult to tell with certainty.

With our backs against the counter Howard and I look through the window past the pumps to the road. From just after the second war to the mid 1970s, those were the glory days of the highway, Howard says, the place full of Americans drawn to the nine lakes within a nine-mile radius of Mountain Grove. But the strong Canadian dollar and high gas prices ended that. The building of Highway 401 to the south didn’t help either, he says.

Howard leads me from the store to the edge of the road. We look up and down the highway and wait. Finally a car passes. He asks if I heard the noise. I didn’t. The wheels were hammering, he says, because of tar poured into cracks on the degrading surface. Listen again, he says. In the distance six cars lean over the centre line looking to pass the tanker truck they’re following. Howard shakes his head. As they drive by each time an axle crosses a tar strip you can hear a soft dull thud like a pool ball hitting a bumper. When it was last repaved, in 1993, a worker told Howard that the province could have spent extra for a more durable surface, but they refused, so it’s falling apart. Howard claims he has figures that say 600 to 800 big trucks pass daily and that 1,334,000 vehicles pass annually. But it’s not enough; in over an hour only one car stops for gas. A station down the road has been for sale for two years but no one is interested. Howard talks about moving to Florida but he sounds unsure. He’ll likely just carry on until he doesn’t want to do it anymore, and then stop cutting the grass and retreat up the hill to his house. Once or twice a day a car will stop, out of habit, but a log propped on a sawhorse across the drive will tell everyone else that he’s done for good.