The big-inch cruiser is a North American phenomenon. More specifically, it’s a North American “man” thing. It would seem that males here need accoutrement to enhance their manhood: from over-powered, oversized SUVs to implant-enhanced women to Viagra. Few things exude virility more than a long-stroke crankshaft thrusting pistons inside the splayed cylinders of a V-twin that is wrapped in chromed steel and fat tires. Girly bikes these are not.

Although we are not suspect of our manhood here at Cycle Canada, at least not publicly, we tested a trio of these motorcycles. Originally joining Suzuki’s Boulevard C109RT, Victory’s Hammer and Yamaha’s Raider was Harley-Davidson’s Rocker C, but a last-minute phone call from importer Deeley Harley-Davidson advising us of a handling problem excluded it. Despite our Harley-less group, differing takes on the cruiser are represented. Suzuki’s Boulevard C109RT is a classic cruiser with skirted fenders, the Victory Hammer is a sporty power cruiser and the new Yamaha Raider a stretched out performance custom.

The new-for-2008 Suzuki Boulevard C109RT is full of contradictions, excelling in some areas and underperforming in others. A potent M109R-derived engine that has been reworked to make it touring-friendly powers the undisputed technological leader in this group. The eight-valve V-twin receives revised intake cam timing, a 20-percent increase in crank inertia and 2 mm smaller throttle bodies (now at 52 mm), changes aimed at smoothing its power delivery and -boosting low-end torque. What has not changed, however, is its counterbalanced 54-degree V angle, massive 112 mm bore (mated

to a 90.5 mm stroke for displacement of 1,783 cc), staggered crankpins (giving it perfect primary balance as on a 90-degree twin), combined chain and gear-driven double overhead cams, dual plug heads and dry sump lubrication. Its GSX-R -heritage, so proudly proclaimed in the sales literature, makes it the only bike in this test to sport liquid cooling.

With its impressive spec sheet, it’s no surprise that it’s the power king with a claimed 114 hp. Although Suzuki has not released torque figures for the C109, the M109R claims 118 lb-ft, which the C109R is said to exceed. While the C109R trounces the others at higher rpm, fuelling glitches mar low speed operation. This, surprisingly, is despite its use of a dual-butterfly fuel injection system and exhaust-mounted butterfly valve. Throttle modulation is unpredictable at lower engine speeds, the bike often surging ahead in an almost violent manner, hardly a desirable trait on a 357 kg (787 lb) bike.

To make matters worse, despite staggered crankpins, counterbalancer and rubber-mounted engine, it shakes profusely at low rpm, and not in the soothing manner sought by big-twin lovers. While it is somewhat tolerable at constant throttle, any attempt to accelerate from low revs has the big twin quaking, all the while delivering very little in the way of meaningful acceleration. Further exacerbating the situation is a tall fifth gear, which has the engine turning in the shaking zone when accelerating from speeds below 140 km/h. A quick downshift delivers serious forward thrust and smoothes vibration considerably, making it both the roughest and smoothest engine in the group. In order to overcome vibratory top gear cruising, one tester left the Suzuki in fourth gear at highway speeds, which gave smooth 100 to120 km/h cruising. Predictably this caused fuel consumption to drop from a best of 7 L/100 km (40 mpg, the worst of the group) to a midsize car-like 8 L/100 km (35 mpg).

The Boulevard’s gearbox has an industrial feel, with a deliberate stab at the heel-toe shifter causing an audible clunk of massive cogs. Although it lacks the finesse of other Suzuki models, it seems entirely appropriate on this brute—a feather-light supersport transmission wouldn’t seem right. The C109RT is the only shaft-driven bike of the trio, and some driveline lash is present, especially at low speeds where the throttle already requires a steady hand.

Shaft drive also adds unsprung weight, and combined with the C109R’s limited suspension travel and lack of damping, it gave a harsh ride on anything but perfectly smooth roads. While the broad and cushy seat does help limit the damage, this is not a bike to ride in the Iron Butt rally. The laid-back riding position further compromises rider comfort in anything but low-speed city cruising, as wind pressure causes you to constantly tug at the wide handlebar. The fix for this, of course, is to install the RT’s standard windscreen, but we were looking for maximum macho points in this test, so the screen stayed off. Also, while the other bikes are quite narrow at the seat-to-tank junction, the C109’s excessively wide seat and fat fuel tank make it feel like you’re straddling a horse.

Fat tires and a wide buckhorn handlebar give the bike a vague feeling in the corners, and the 240-series rear tire (not the fattest in the group; the Victory’s 250-series has bragging rights) make the bike want to stand up through turns, requiring constant pressure at the handlebar. On gentle rides through sinewy country roads, the C109RT can be entertaining, so long as bumps are infrequent and turns not too tight, as low-hanging floorboards limit cornering clearance.

Despite having an impressive collection of braking components (it’s the only bike with a linked braking system; the front brake lever works the two outer pistons in each three-piston front caliper while the rear pedal activates both rear caliper pistons as well as the middle piston in the front calipers), the C109RT’s brakes lack feel and power. Effort required is significantly higher than the other two bikes and feedback is well below average.

Mirrors remained free of vibration and the tank-mounted instruments were easier to read than the similar set up on the Yamaha. Attention to detail was average, especially compared to the Raider, as the excess of exposed wires and cables took away from its cleanliness.

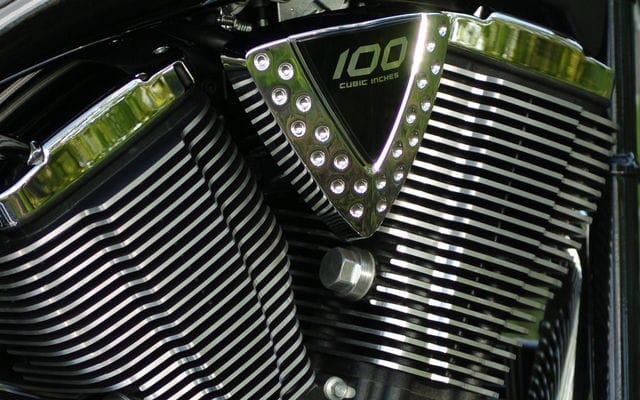

The Victory Hammer, at 1,634 cc, has the smallest displacement engine in this group. Introduced in 2005, the Hammer represented the Minnesota-based manufacturer’s entry into the power cruiser category, against such luminaries as the Yamaha Warrior and the Suzuki M109R. Its Freedom 100 air-cooled V-twin has been updated for 2008, with a host of changes aimed at reducing emissions and fuel consumption while improving rideability and power. Upgrades include a new closed-loop fuel injection system with a reprogrammed ECM that provides individual cylinder mapping, as well as new injectors, throttle body and oxygen sensors. A new airbox enhances breathing while a reduced compression ratio (from 9.8:1 to 8.7:1) provides better knock resistance, while also permitting more ignition advance at low rpm for improved low-end power and sharper response. New camshaft profiles also contribute to its claimed output of 85 hp and 106 lb-ft of torque, the latter a respectable number for such a “small” engine.

Vibration and noise were reduced through changes in the primary drive, a split clutch gear, and redesigned crankcases and engine covers, while engine internals were redesigned to improve smoothness. Revised internal oil-passage routing and a re-positioned oil cooler help stabilize operating temperatures and improve durability. Revised transmission ratios (a lower first and taller sixth gear) improve initial acceleration while providing more relaxed (and economical) highway cruising. The efforts directed at the American twin have largely paid off, as the Freedom is generally smooth and feels refined across its rev range, with only a consistent and pleasant V-twin throb reaching the rider. The changes aimed at softening power delivery provide smooth and predictable low-speed throttle response, a striking contrast from the Suzuki.

While none of the bikes featured here have silky-smooth shifting, the Victory is definitely the clunkiest of the bunch, though its six gears are well spaced. Like the Suzuki, top gear is very tall, leaving the engine loafing at highway speeds. Overtaking requires a downshift to fifth, though even this leaves the Hammer at a disadvantage when accelerating past slower traffic compared to its larger-displacement adversaries. This displacement disadvantage did give the Hammer the edge in fuel consumption, averaging 5.9 L/100 km (48 mpg), the best of the bunch.

The riding position on the Victory is much less tiring than the Suzuki’s, as the rider is more upright, resulting in dramatically less wind pressure at highway speeds. But the Hammer’s seat is a disappointment; it’s overly firm and the shape restricts rider movement and digs into inner thighs and tailbone.

Handling is surprisingly agile, aided by a rigid inverted fork, firm spring and damping rates and sporty front tire profile. As expected, the 250-series rear tire causes the bike to stand up in corners, and the Hammer requires constant pressure to maintain a lean, but this tendency is much less pronounced than on the C109RT.

In addition to powertrain improvements, the Victory also received upgraded brakes for 2008. New front and rear calipers, rear master cylinder, discs and brake lines give the Hammer good feel and strong stopping power. The analogue instruments, which include the only tachometer in the group, are well positioned and easy to read, and mirrors give a wide but blurry view at all speeds. The Hammer is available in the widest range of colours, and for the real badass, the blacked-out Hammer S is one of the meanest looking power cruisers on the market.

The Raider represents Yamaha’s first venture into the raked-out custom bike market, a first for a Japanese manufacturer. Its long-stroke (the longest of the three bikes at 118 mm), 48-degree, air-cooled V-twin displaces 1,854 cc, and has closed-loop fuel injection. While the low-tech mill makes use of pushrods, it has an impressive 123.7 lb-ft of torque at only 2,500 rpm. Power feeds through a five-speed gearbox and the 210-series rear tire (the widest ever for Yamaha, but the narrowest here) is driven by belt.

Out on the road, the Raider has the liveliest engine of the bunch. Response at any speed and in any gear is instantaneous, the bike surging ahead with a rewarding rush of acceleration. Reaction to throttle at low speeds is more sudden than on the Hammer but quite manageable. On the highway, the engine throbs with just enough vibes to remind you that you’re on a big twin. The Raider also has the most raucous sound of the trio, the others sounding subdued by comparison. Despite tallish gearing, passing does not require a downshift, even when revs feel ridiculously low – how low is uncertain, as the Raider has no tachometer. Shifting, as on the others, is stiff but positive. Fuel economy was a close second to the Hammer at 6.3 L/100 km (46 mpg).

A high-tech chassis offsets the engine’s low-tech design. The Raider is the only bike here with an aluminum frame; a cast double-cradle design that mounts the engine rigidly. Rear suspension uses a linked, horizontally positioned single shock, which is connected to a cast aluminum swingarm that mimics a hardtail look. The front end is what separates the Raider from the rest of Yamaha’s cruisers. Marketing folk clearly wanted to tap into the boutique custom bike market, which is said to outsell classically styled cruisers by a 2 to 1 margin. In order to achieve the desired raked-out look without penalizing ride quality with heavy steering, engineers developed tripleclamps that add an additional 6 degrees of rake to the 33.2-degree steering head angle. This provides a total fork angle of 39.2 degrees while maintaining a manageable trail measurement of 152 mm.

The styling treatment further extends to the 21-inch front wheel, the first time a large-diameter hoop is used on a Yamaha. Engineers considered fitting a wider rear tire, but settled on the 210-series so handling wouldn’t suffer, though the 7.5-inch rear rim can accommodate a wider tire for a custom build. While one could be forgiven for being cynical in response to Yamaha’s claims of agility, the Raider was the most responsive bike of the lot. Its low centre of gravity, comparatively narrow rear tire and trick front-end geometry combine to produce steering that is light and precise, the bike responding instantly to handlebar input without the heavy, vague feeling that plagues the other two.

The upright riding position is surprisingly accommodating, and combined with a roomy, supportive seat and soft suspension rates, ride quality is plush. While rough patches of pavement transmit some choppiness to the rider, an all-day ride on winding roads is entirely possible on the Raider, something that can’t be said about the others. Stability in the corners is excellent on smooth pavement, although the bike does weave through bumpy sweepers when speeds are raised a notch, a trait typical of soft suspension settings.

The brakes are another area where the Raider excels, providing the most power and the best feel of the group. The effort required is light and predictable. Not surprisingly, brake dive is significant given the soft spring rates. Good attention to detail is evident throughout the motorcycle; wires and cables are hidden and the look uncluttered. But it is not perfect. Mirrors are blurry at all speeds and the tank-mounted instruments require a distracting look away from the road.

The $17,799 Suzuki Boulevard C109RT has some notable strengths, but there are simply too many chinks in its armour. Tough as we are, no one enjoyed the pounding dished out by its harsh suspension, and we found its generic styling lacked character. It ranks third.

The Victory Hammer is stylish and sporty, but its painful seat, clunky gearbox and cumbersome handling kept it from earning a higher ranking. At $19,803 it is also the most expensive bike on test, so it, too, finishes behind the Yamaha.

The $17,999 Yamaha Raider rides away with the laurels; it was the machine we most wanted to ride, while, at the same time, had the most exaggerated cruiser look. When it comes to flexing muscle, sometimes a touch of fineness goes a long way.

From the Saddle

I’m always at a loss while reviewing cruisers, especially showy, big-bore machines. If you’re on the way to the strip joint for a table dance, comfort, handling and braking are irrelevant—just choose the machine that most arouses you, slip on a half–helmet, and go.

My table dance bike is the Victory, with its understated and muscular looks and smooth and refined engine. But the handling, while surprisingly good given the width of the rear tire, is ponderous, and the too-short seat made my body go numb from the nipples down after an hour in the saddle.

What is most surprising about the Yamaha is that it rides like a regular motorcycle despite the kicked out fork. The seat is comfy, too, as it’s much longer than the Victory perch. But styling lacks the polish of Yamaha’s handsome Roadliner, and looks to my eye too derived from the Virago.

Throwing a leg over the hood of a car and trying to ride it like a motorcycle is a loose approximation of the Suzuki’s riding position. Even among these big bikes it’s huge, and while the engine is willing, it’s a lot of machine. So it’s the Yamaha over the Victory for riding, the Victory over the Yamaha for posing with the Suzuki taking the trophy for mass appeal. —Neil Graham

Looking at the three bikes through a cafe window, I considered the metric tonne of chrome and attitude parked outside. The brazen display of metallurgy was barely contained by a parking space big enough to swallow a Lincoln Navigator, which I wished I had been driving; nothing takes the shine off a cruise like single-digit temperatures and pouring rain.

After two days of riding, it was obvious that the Suzuki was at cross-purposes with its motor. At cruising speeds its erratic fuelling was a frustration, causing the bike to lurch and buck until smoothed by a liberal amount of throttle. It has an engine better suited to a sportier bike.

The Hammer, contrary to its name, was the most refined, with precise fuelling and a top gear so tall that it left me wondering if the motor was running, even at 120 km/h. Unfortunately, it also had the worst seat, as each rider found new ways to contort their body searching for relief from the pain.

This leaves the Raider, the most engaging of the three to ride. Pulling hard from low revs with a deep robust sound, the torque maintained my excitement in the city and on the open highway. At a rest stop, an elderly lady using a walker tells me, “it’s a handsome machine”. I fully agree. —Uwe Wachtendorf

I don’t think I’ll be rushing out to buy a heavyweight cruiser anytime soon; this category of bike is simply too narrowly focused for my liking. This is especially true of the Suzuki C109RT, which despite its hell-strong engine, is simply too flawed in the critical areas of comfort, handling and braking to host me for the daylong rides I cherish.

The Hammer, admittedly a good all-round cruiser package, is let down mostly by its uncomfortable seat and lazy handling. Who really needs a 250 mm wide rear tire anyhow? I must confess that the softening of its power delivery at lower speeds had me longing for more; this is a power cruiser after all.

The Raider comes closest to being worthy of purchase, as it is an amazingly fun bike to ride and, ironically, the least penalized by the form before function credo that guides most cruiser design. —Michel Garneau