High-horsepower sport bikes aren’t always fun to manage. Handling modern open supersports—now approaching 200 hp—requires a level of skill few possess. Even the most experienced rider approaches the right grip on one of these powerhouses with a touch of trepidation—twist it too hard and it’ll bite.

Middleweight supersports are more manageable but they lack the bottom-end grunt that makes a machine easy and fun to ride around town. Unless you spin their engines into five-digit revs, limp power delivery excites about as much as a thong—on a guy. And I don’t care what your sexual orientation is, that’s just not right. Twins and triples offer a muscular powerband and slender profile, as well as lustful sound, but they still can’t match singles for agility and lightness.

Singles, on the other hand, lack outright power and often vibrate with bone-rattling intensity. They’re simple and inexpensive to maintain, but in terms of outright performance, fuel-consumption numbers are more stirring than lap times.

KTM specialises in singles—powerful ones. After riding the latest 690 Duke and 690 SMC at the press launch near Almeria, Spain, my pre-conceived notions of mono-cylinder street bike performance have been reset. If it weren’t for the once-every-360degree power pulse of its engine, it would be easy to mistake the Duke I’m riding for anything but a single. Twisting the throttle between tight, guardrail-less turns on narrow mountain roads gives acceleration to match the strongest sport bikes. The bike claims 65 horsepower, a figure only previously possible on full-blown racing singles. That number might not impress hardcore knee-sliders, but consider that with a dry weight of just 148 kg (326 lb), the Duke undercuts the lightest 600s by about 13 kg (29 lb).

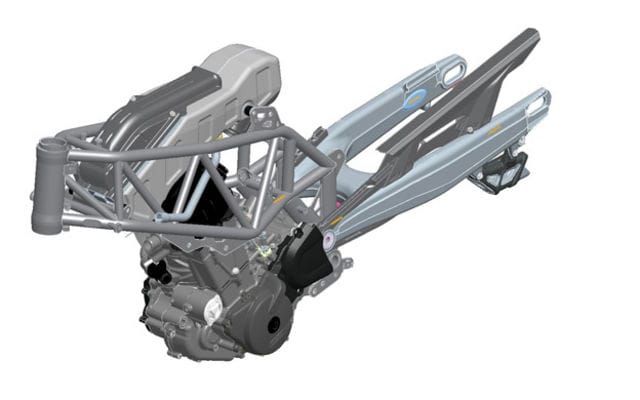

Before digging into riding impressions of the two machines, it’s important to note that they share only engine and switchgear. The SMC is closely based on the Enduro model, but with firmer supermoto tuned suspension, laced 17 inch wheels and stronger brakes. Its trellis chrome-moly frame features slightly altered steering geometry, an outboard mounted gravity die-cast aluminum swingarm, and a unique plastic subframe/tailpiece that incorporates the 12-litre fuel tank. Its engine is located farther forward in the frame and the airbox is mounted above the engine, where the fuel tank is usually located.

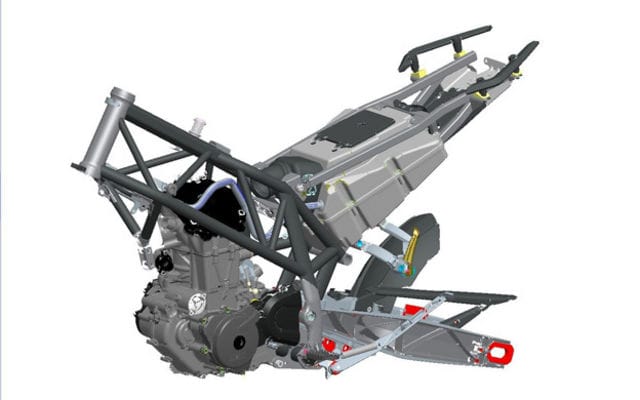

The Duke’s trellis frame is more rigid, with larger diameter main tubes and a wider rear section, with a distinctive externally ribbed, pressure die-cast aluminum swingarm mounted inboard of the frame tubes. The Duke’s airbox is located beneath the seat, supported by an aluminum subframe, and the fuel tank is in its usual location above the engine.

The SMC’s exhaust system features a muffler mounted high and on the left side of the bike, and it gets hot enough to burn, something that won’t happen on the Duke, as its exhaust can is mounted, Buell-like, below the engine. Passenger footpegs are installed on the Duke, and are included with the SMC but not installed.

The main feature of the new 690 models is the latest 654 cc LC4 engine. Introduced last year on the 690 Supermoto, a bike we declared the “most powerful single-cylinder motorcycle we’ve ever ridden” (CC, July 2007), it seriously kicks ass. Electronic fuel injection feeds a 46 mm throttle body, but more significantly, the LC4’s Keihin EFI is a true fly-by-wire system, very similar to that on the Yamaha R6. The throttle plate is operated via a servomotor, but can be closed manually by the throttle cable should a glitch develop in the system. This electronic control has allowed engineers to offer several power modes, selectable via a dial switch located under the seat on the SMC and behind a right-hand side frame rail on the Duke. Three power curves are available; a standard curve (#2) allows full power at high rpm with softer response at lower speeds, an aggressive curve (#3) with quicker throttle valve opening at lower rpm for sharper response, and a low power curve (#1) that reduces power 30 per cent throughout the rev range, limiting output to 48 hp. A fourth curve is available on the SMC for poor quality, low octane fuel.

The riding position on both bikes is dirt-bike-like, which enhances control and weight transfer when flicking either machine through tight switchbacks. The upright riding position is also more comfortable than the crouched-for-speed stance of a supersport, unloading a rider’s wrists and back, though at higher speeds you’ve got tiring windblast to battle.

The Duke’s seat (865 mm/34 in. seat height) is firm, yet wide with good support, and remains tolerably comfortable after completing our 120 kilometre loop twice. According to KTM’s product manager, Joachim Sauer, the SMC’s narrower, harder seat is “designed for aggressive riding,” which in KTM speak means find a very twisty road and have a go at it, because if you sit still for just 15 minutes your ass aches into the next day.

At least the pain inflicted by the SMC’s sadistic saddle (900 mm/35.4 in. seat height) isn’t compounded by vibration. A gear driven counterbalancer reduces engine shaking to a mild murmur felt mostly through the Renthal tapered aluminum handlebar. The reduction in vibration over the previous LC4 paint shaker makes the new 690 models much more appealing. The only intrusion to smoothness is a mirror blurring shudder, present at 100-110 km/h (4,300-4,500 rpm), which is more noticeable on the Duke, but much less than on any Ducati.

Overall gearing is tall on both machines, meant to appease emissions regulations, and is a bit taller on the Duke (40 rear sprocket teeth versus the SMC’s 42), as its less restrictive airbox produces more intake noise (hence the SMC’s slightly lower output at 63 hp).

Styling not only differs between the two models; it is also a clear indication of each bike’s intended use. The SMC behaves exactly as it looks: like a dirt bike converted for supermoto use. As such, it is focused more towards track use, and its streetability is compromised. Steering is lightning-quick, at the expense of high-speed stability, and the WP suspension is too firm for comfort as delivered, though ample adjustment is available at both ends (rear suspension on all 690 models is linkage type, a first for KTM). It’s twitchy at speeds above 120 km/h, mostly induced by the leverage offered by the wide handlebar, but also by a more forward-biased weight distribution compared to the Duke.

It has a restless nature and snappy throttle that will entice delinquent behaviour in the most obedient of riders. The SMC’s quicker steering pays dividends at the improvised supermoto track our hosts lay out in the hotel parking lot. There, it easily flicks into the tight, first gear turns, diving into and out of them with astounding front end feedback and rear grip. I’m often surprised by the amount of front wheel grip, sometimes expecting to find myself tumbling after trail braking so hard and deep that it seems unnatural that the bike remains upright. Had I fallen off and failed to pick the bike back up within five seconds, a roll-over sensor would cut the engine and the ignition switch would need to be turned off then on again to reset it.

A slipper clutch (also standard on the Duke) greatly improves corner entry. The SMC is a bit too ponderous at 140 kg (310 lb) dry for the super tight parking lot track and doesn’t have the bicycle-like agility of the 560 SMR I raced last summer (CC, Nov/Dec 2007), but it scores high fun factor points.

The Duke is alluring, with stacked beam headlights in a sharp looking nosepiece, aggressively angular lines and cast wheels. It is a better balanced street bike, combining sharp handling with better high speed stability and improved comfort from softer suspension settings and a better seat.

KTM has greatly smoothed the previous model’s rough edges, while maintaining a level of sportiness that is in keeping with the firm’s “Ready to Race” tagline. It exhibits standard bike civility around town, while handling the twisties like a true sport bike. Its broad power delivery makes shifting mostly unnecessary, even if the gearbox does shift with typical KTM precision and ease. Slightly taller gearing requires a bit of clutch slippage on takeoff, and quick passing from 100-110 km/h begs a downshift, though a short highway stint reveals effortless cruising at 140 km/h and ample reserve acceleration from 160 km/h.

I’d consider gearing the Duke like the SMC to get the latter’s sharper low speed throttle control and reduced top gear shuddering at the speed limit. I also take the Duke to the supermoto track, where it surprises me with its agility, despite its added weight. It also exhibits excellent front wheel grip and feedback, even though it rolls on harder Dunlop Sportmax tires (the SMC comes standard with Pirelli Supercorsa Pro tires), and turning transitions are only slightly more laborious.

Brakes are similar on both machines, with Brembo four-piston, four-pad radial-mount calipers squeezing different 320 mm discs because of different mounting patterns (spoke wheels on the SMC versus cast aluminum Marchesinis on the Duke). Front brake power will easily lift the rear wheel with a two-finger squeeze, though modulation is easy to manage, and no fade is discernible after dozens of laps.

I sample the three power curves on both bikes. The aggressive curve causes the throttle to be a bit too choppy at low rpm for practical street use, but provides excellent response when driving out of the slower turns at the improvised supermoto track. The standard curve is best suited for everyday use, providing smoother throttle transitions, while still offering full power when needed. The low-power curve seems redundant, though it will probably keep you from getting in trouble, as both these bikes constantly tempt you to snap the front wheel skyward in the stronger power settings. One thing to note is that once you choose a power mode, you’re stuck with it until you stop, unlike some Suzuki and Benelli models, which allow on-the-fly power mode selection.

KTM has long produced high quality, high performance dirt bikes, expanding in recent years into the street bike market. Having met the engineers and management team at the press launch, I can say with certainty that you’ll never see a production KTM cruiser. You will see an increased street presence and the focus will remain on high performance. The $9,898 SMC will be a harder sell, with a focus too narrow to be practical. The $10,498 Duke, however, should fly out of showrooms and will, in my view, redefine and reinvigorate the single-cylinder street bike market.

Photos: G. Freeman, F. Montero and H. Peuker