“You couldn’t really start out with the idea of making a 2,300 cc motorcycle,” says a product manager from Triumph, “it started as an idea and just grew and grew.” And grow it did. Manufacturers, with near phallic obsession in the years surrounding the new millennium, engaged in a battle of one-upmanship that gave us first 1,800 cc V-twins and later a full 2-litre Kawasaki V-twin cruiser. As outrageous as this was, who could have guessed that a demure English company, with a history of balanced sporting motorcycles, would have, in 2004’s Rocket III, introduced a 2,294 cc giant that dwarfed all those that came before?

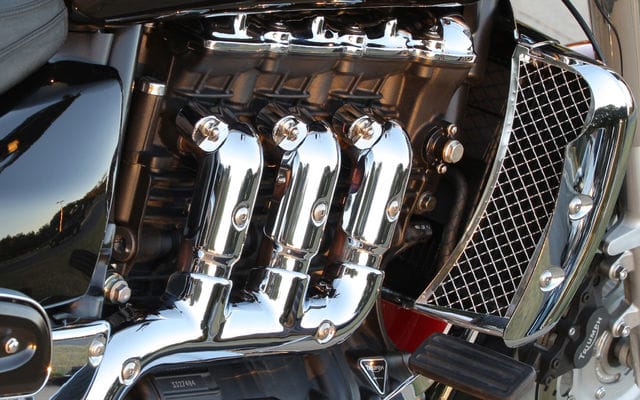

Just as unusual was the engine’s orientation, its longitudinal triple the first since the demise of Indian’s Four in 1940 to eschew transverse mounting in favour of a fore-and-aft configuration. And now, with the introduction of the Rocket III Touring, Triumph wants to show that the platform is good for an honest-to-goodness motorcycle—and not just a cruiser packing heat.

The Rocket III remains unchallenged (wisely, perhaps) as motorcycling’s displacement king, but it was a surprise to learn that even before the cruiser’s launch in 2004, Triumph was already at work on its touring brethren. "Initially we didn’t think we’d have to change that much,” said a Triumph rep, “but the further we got into it the more we realized that it would be an all-new motorcycle.” The only chassis parts interchangeable between the two Rocket III models are the taillight and the mirrors. First to go was the cruiser’s 240 mm rear tire, for issues of handling as well as packaging. Any modern bike that claims touring capability requires hard saddlebags, but fitting panniers outside a 240 mm tire would give a motorcycle the breadth of a DC-8’s wingspan—hardly an attractive or practical proposition.

My time aboard Triumph’s original Rocket III has been limited, but it only took exiting a parking lot to realize that any bike with a back tire that wide would exhibit peculiar handling characteristics. Triumph, Victory and other manufacturers stress that they go to great lengths to get good handling out of such a wide tire. But the caveat always attached is for a tire of this width; if you ignore the qualifiers you’re always aware of the presence of the fat tire, as the motorcycle is reluctant to lean into corners.

Texas hill country outside San Antonio is a region of smooth, gently curving roads. Unsurprisingly, it is also one of the preferred locations for manufacturers to launch cruisers. The change to a 16-inch diameter by 5-inch wide rear rim and 180/70 tire transforms the Rocket’s handling, and what startles is that the bike feels like a normal motorcycle, despite having an engine larger than those fitted to many cars and a claimed dry weight of a whopping 362 kg (798 lb). With fluids and a rider, it makes for a road-ready weight of more than half a tonne—and that’s before toothbrushes, boxer shorts and a friend to take in the scenery. Triumph, in explaining the bike’s surprisingly friendly nature, points to a giant 17 kg (39 lb) crankshaft mounted low in the chassis that gives an ultra low centre of gravity, and muted torque reaction tempered, in part, by an engine balance shaft and final drive shaft spinning opposite the crank’s rotation. Blipping the throttle at a standstill, the Rocket III Touring displays less torque reaction than a BMW Boxer, despite nearly twice the displacement.

Leaving San Antonio for the surrounding countryside in morning traffic, the drivetrain is impressively smooth and snatch free. Perhaps the heavy crankshaft helps, but regardless of the reason, the Rocket III is without the choppy throttle response that characterizes many of today’s fuel-injected motorcycles. Because of the engine’s substantial displacement, high compression isn’t needed to produce big power, and the compression ratio is a low 8.7:1. The Triumph rep smirked when he told us that the engine, almost laughably, has been retuned for more torque versus the Rocket III Classic. Triumph claims 154 lb-ft of torque at a just-off-idle 2,000 rpm from the 101.6 x 94.3 mm, 120-degree triple, as measured at the crankshaft.

Claimed crankshaft horsepower of 107 hp is at 5,400 rpm. Those numbers—shockingly high torque and horsepower lower than Triumph’s own Daytona 675 sport bike—make for power characteristics almost without equal in motorcycling. Because the engine’s virtually step-less powerband is as flat as a western prairie—regardless of road speed or engine revs—a mitt of throttle gives a strong, almost electric-smooth forward shove that makes the bike feel slower than it is. The only other motorcycle in my experience with these characteristics is the Chevy V-8-powered Boss Hoss but—and you need to trust me on this—that’s a direction you don’t want to go.

Cornering clearance is good—exceptionally good if you compare it to the cruiser competition, as I only decked the footboard a few times (riding hard is a press-launch tradition; few will touch hard parts in normal use). A Triumph staffer noted that most UK employees are sport bike enthusiasts, and the footboard design shows that heritage. They’re hinged, have bushed pivots, rubber bump stops and steel replaceable wear plates.

There is more clever design in the heel-and-toe shifter, which alleviates the irritation of this deemed-necessary touring-bike addition. The heel portion is nicely sculpted and tucked away at the end of the board, which also allows the foot to move around freely, so unless you habitually ride with flip-flops or snowshoes you can just use the toe part of the lever normally and ignore the rest. Additional space on the footboard allows, with the foot in the most rearward position, a near standard riding position.

Allied with a broad saddle, comfort for most of our 300-kilometre ride is good, but on the way back to the Alamo, my hind end would have preferred a foot position further back to help alleviate tailbone pressure. Suspension settings are soft but not soggy, and the twin-shock rear end is without the harshness that often mars this traditional design. A 22-litre fuel tank is slightly smaller in capacity that the Classic’s 24 litres, but if fuel consumption resembles the 6.5 L/100 km (44 mpg) we experienced during a recent Rocket III Classic test, range should be somewhere near 340 km.

Heavy-footed provocation of the rear brake will cause it to lock, but the front brake, in typical cruiser fashion, lacks initial bite, but with a hard enough squeeze the Rocket slows quickly enough. Cruiser manufacturers en masse have seemingly decided that fans of foot-forward motorcycles lack the subtlety to modulate sensitive front brakes. Your $19,999 investment (two-tone paint costs an additional $300) includes a windshield that Triumph developed in conjunction with American windshield maker National Cycle. It is intended as a “look over” shield; eyes look over the top and not through. This style of windshield is not particularly sophisticated, as it punches a hole in the wind as opposed to thoughtfully channeling airflow, but it works well enough, and with two large stainless levers it removes easily without tools.

Capacity of the stock saddlebags totals 39 litres and lids are lockable with the ignition key, though my tester required a very firm push for the lids to properly secure. A nice touch is that the bags, once removed, are designed to stand upright on a flat surface, so no more bags rolling off the sidewalk.

Triumph increasingly understands that by the time the first payment clears, cruiser buyers are queued up to buy accessories, and already 70 items are in the catalogue. Seats, higher and lower windshields, and the usual array of chrome doodads awaits, but the cheekiest is the black cam cover that retails for $330 and replaces the chrome cam cover already on the bike, a sure sign that Triumph is still trying to decipher the North American rider—this is usually done the other way around.

What surprises most about the Rocket III Touring is that it nearly, if not completely, allows you to forget that you’re on such a behemoth. Clutch pull is reasonable and shifting action of the five-speed transmission is light, but early in our ride I make a timid stab at the lever and am met by the sound of gears in great distress, like I’d botched a double-clutch downshift on a Kenworth, a mistake I don’t let happen again. I’m not sure that any of us really need a motorcycle this big, but we don’t really need 180-horsepower sport bikes either, and the Rocket III Touring allows me to dust off the most overused cliché in all of motorcycling. The torque, you ask, what’s it really like? To which I say this: It’s stump-pulling.