Shhh… There it is. See it hiding in the brush? An adult Ural Gear-Up ready to pounce on unsuspecting prey. Or, more likely, abandoned by a dejected Neil Graham.

A little confidence is a bad thing. The path through the trees ahead of me is narrowing and I have that feeling of invincibility that precedes most disasters. I’ll blame this unwarranted confidence on my Ural Desert Camo Gear-Up sidecar rig with its psychedelic orange and green livery, its purposeful 2WD logo and its prominently mounted spare wheel. Something that looks like this can’t get stuck.

My day at the 2007 CURD—an awkward acronym for Canadian Ural/Dnepr riders group—rally just outside of Peterborough, Ont., begins well enough. I register at the gate, receive a plastic drinking mug with flashing LED lights, and then join a tech session already in progress. The CURD website described the association as “a group of people loosely joined by fear and the bond of motorcycling,” but those attending the tech session are neither fearful nor bonding. They look like they’re falling asleep.

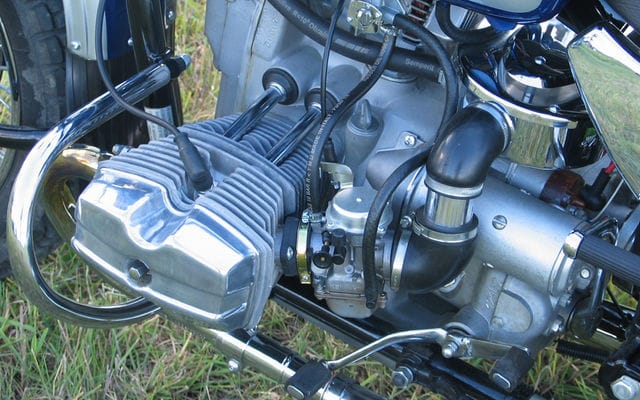

Heading the tech session is Ural dealer Ken Beach, proprietor of Old Vintage Cranks in Hillsburgh, Ont. Beach confesses that while he still owns a bevel-drive Ducati 900SS, he was always attracted to Ducati’s 500 cc parallel twins, widely considered Bologna’s worst motorcycle. “But then again I guess I just like terrible things,” he says, before rethinking his comments, “no, wait, don’t put that in.” Beach covers valve adjustment, carburetor synchronizing and oil changes, and traces his love of Russian motorcycles to their uniqueness and simplicity, the latter encouraging active owner involvement in servicing and customization. Customization? Really? “It’s true,” Beach says, “you see a lot of bikes with deep oil pans.”

After the tech session I stroll over to a pristine white machine and meet Konrad Zeh. His is a brand new machine with only 49 kilometers, and he tries to sell me his previous rig, an ’03 Ural Northern Cruiser, for $8,000. Why did you buy a new one, I ask. “Why do people buy new cars?” he replies. When I don’t have an answer he continues. “I like it because I don’t have to put my feet down and it’s good on streetcar tracks. My wife uses the old one for shopping,” he adds, looking at me expectantly, as if word of his wife’s shopping may cement a deal. Leaning over the fuel tank of his showroom-fresh rig I ask if he knows that his tank decal is coming off. “It’s Russian,” he says with a shrug, not feeling the need to explain further.

My sidecar experience totals 10 kilometres on an Ural rig three years ago, so I seek advice before I leave on the scavenger hunt. “There is a technique to riding them,” says an owner with a grave expression, “go slow.” I fall in behind Dave Corbett and his 2007 Ural Patrol. Corbett admits that he bought it as a toy to go along with his Gold Wing and’69 Shovelhead, and hopes that it will be good for getting into the hunting camp in fall, “but I still think I’ll take along a block and tackle, just in case.” The scavenger hunt is a three-hour back road tour that ideally requires a navigator, as the directions (“go left after the bridge but if you go over the hill you’ve gone too far”) have me riding with one hand and holding the directions aloft with the other. One of the first items on the scavenger hunt list is Queen Anne’s lace, and we’re directed to a specific spot on a country road to look for it. An elderly couple on a Harley sidecar rig are holding aloft a plant and wondering whether they’ve found it. Corbett takes his helmet off. “That’s not Queen Anne’s lace,” he says, “that’s ragweed,” which sends the couple head-down back into the ditch.

My interest in combing ditches on a hot July afternoon fades and I set off on a pleasure ride. What was most memorable about my previous Ural experience was the crudity of the machine, especially its transmission. I remembered thinking at the time that the term gearbox—as in gears randomly tossed in a box—was only too appropriate, as the crunching while shifting was horrifying, and only comparable in my experience with garden tractors and postwar hand shift Harleys. But this new machine is a revelation, as shifting is accompanied by a crunch of no more severity than that of a vintage BMW. Later I ask Beach about the improved shifting. “Ah, so you liked those new Austrian-made gears?”

Many two-wheeler aficionados view sidecars as an abomination, mid-way between a bike and a car but with neither the motorcycle’s agility nor the car’s roof. Sidecars are also plagued, so the stories go, by handling peculiarities. At a popular motorcycle hangout I overheard a man explain to his companion that the first and only time he drove a sidecar outfit he immediately left the road and plunged down a ravine—and the ravine was on the far side of the road. I suspect some are confused because typical two-wheeler counter-steering is not applicable to a sidecar rig. If you push on the right end of the handlebar you go left, and not right as you would on a two-wheeler, but I don’t find adapting to the steering difficult. If an action causes the machine to go the wrong way, then survival encourages the operator to try something else, and the opposite input seems the most logical.

Riding the $13,595 Ural Desert Camo is engaging, even at moderate speeds. It takes some practice to become accustomed to watching two tracks on the road surface ahead—as you would in a car—instead of one as on a solo motorcycle. On one occasion the sidecar wheel whacks a dirt clump on the edge of the road because I swerve to miss a pothole with the front wheel. Power is moderate, and during a high-speed run with my body flattened to the tank I only read 110 km/h on the speedometer. The upside of its slow march is that even fleeing the scene of a murder police will be unable to tag speeding onto your charges.

The riding position is 1970s standard, so legroom is good and the wide handlebar is a necessity for leverage. The solo tractor-style saddle is a disappointment, as it’s mounted on rubber blocks that have an unacceptable amount of side play, so as the rig travels down the road your torso wiggles in a to-and-fro squirm. At first it’s fun but it becomes annoying, and over one stretch of wavy pavement my jiggling ass triggers my head to start wobbling and I go into a full body tremor, the human version of a tank-slapper. Later I try an $11,995 single-wheel-drive Tourist Deluxe with standard-style dual seat, and the improvement in comfort is significant, though it doesn’t share the agricultural chic of the Desert Camo’s solo saddle.

Late in the afternoon I stop for water and notice that despite riding on dirt roads my Desert Camo rig is still spotlessly dust-free. The inappropriateness of prissily chugging along smoothly graded roads when I should be out bashing a hole in the forest irks me, and following the directions of Ural importer and local resident Gerry Young, I leave the road behind and start down a two-track trail through the woods, alone. I’m not much of a dirt rider but the macho paint scheme and two driving wheels encourage me to exploit my naivety. Unlike a two-wheeler, where you pick your way around obstructions, the added width of a rig does not allow for subtly, and when I see the trail disappear beneath water I stop and remove my riding jacket and helmet, and selecting low gear and with the two-wheel-drive gearbox engaged I confidently pull forward and sink.

My left wheel has disappeared into mud and the right wheel is spinning madly. The problem is that the left track of the trail is much deeper than the right, and the rig is listing heavily to the left with no weight on the right wheel and a left wheel hopelessly buried. I try reversing, pulling, pushing, cursing and kicking, without success. I find a log to use as a pry bar, but it’s twenty feet long and I can’t move it. I come to the conclusion that I need ballast for the sidecar to aid traction, and devise, ingeniously, a method of driving the rig from the sidecar. But as I’m about to step onto the sidecar cushion I withdraw my muddy boot. I’ve not the heart to step on the virgin vinyl of a brand-new borrowed motorcycle with a filthy foot, so I take my boots off and roll my pants up. Then I start the engine and with my left hand pulling in the clutch I lie across the seat and reach underwater with my right hand and click the shifter into gear. The transmission, now mostly underwater, gives an aquatic clunk.

I dry my right hand on my pant leg then grip the throttle and prepare to launch. It is an uncomfortable position—hands on the grips in the standard manner and toes wiggling to get a grip on the slick vinyl of the sidecar cushion. With a good dose of throttle I dump the clutch and hang my tail out over the right side as far as I dare. The rig wiggles, bucks and slides deeper into the mud. I squeeze the clutch and reconsider. I decide that I’m lacking commitment, that my body is too tentative, so I give full throttle and let go of the clutch lever. This time I take my left arm and reach across my body and lean far past the edge of the sidecar body. I’m now facing backwards in the chest-out palms-to-the-heavens pose that figure skaters use to mark the end of a routine—and it’s working. I look over my shoulder to see where I’m going and the Ural climbs out of the hole.

With my boots back on I try to turn the rig around, but the trail is between two fences and I don’t have the required room. Up ahead I see an area that will allow me to reverse my direction, but lying between the spot and me are another five water crossings—so off come the boots again and ahead I go. This time as I lean across the seat and reach down to the shifter I pull up to select second gear for more speed and momentum, and with a view out the rear of flying mud and darting frogs I make it to the turnaround point.

Facing back around I have six water crossings until I have dry trail, and I clear the first five but at the sixth the Ural hops out of the two tire tracks and buries itself in long grass. And that’s where it stays.

On my cell I call Gerry and tell him that I’ve buried his rig. “Good for you,” he says, and thirty minutes later three men arrive and together we haul the muddy Desert Camo to safety. Back at the campground word has spread, and later that night at the awards presentation I am awarded the “off road” prize of a rubber chicken and a double-extra-large t-shirt. I am tempted to ask if they have the shirt in medium but I stop before I embarrass myself, because Ural owners know that it’s not for the driver. It’s a gift to lure the fattest person you can find into the sidecar, because no ballast means a long walk home from the woods, and I’ll not make that mistake again.