This oddball motorcycle was the invention of a visionary German engineer. As one might guess, the idea never caught on.

Three German engineers, Hans Meixner, Fritz Cockerell (also known as Friedrich Gockerell, hence the “go” in Megola) and Otto Landgraf founded Megola in Munich in 1921 to commercialize a motorcycle designed the year before by Cockerell. Cockerell’s design originally featured a three-cylinder engine located in the rear wheel, which was later replaced by a five-cylinder engine. However, by the time production began, Cockerell hit on the novel idea of switching the motor to the front wheel. Well, the idea wasn’t totally novel, for it had already been attempted in Britain, where Radco produced a FWD prototype in 1919. Wherever Cockerell got the idea, he was firmly convinced that this was the future in motorcycle design. In spite of the many compromises this peculiar engine location entailed, about 2,000 Megolas were built and sold over a five-year period. Worsening economic conditions and rampant inflation in post-WWI Germany forced the luxury machine, as it was then regarded, out of production, to be replaced by a more conventional 175 cc runabout under the Cockerell name. If the idea of a front-wheel-driven motorcycle seems odd, racing one would almost certainly assure you a ticket to the funny farm. Yet in addition to the Touring model, the Megola factory also built a Sport model for competition, which became a regular contestant in both dirt track and road racing events in 1920s Germany. But with no clutch, no gearbox and no front brake, it was better suited for flat-out blasts around paved ovals like the Grenzlandring, or up and down the banked carriageways of autobahn racing, like at the Avus in Berlin.

It was there that the most intrepid of the Megolamaniacs, works rider Toni Bauhofer, averaged a tad under 90 mph in 1924 en route to victory. Later that year he became German champion by winning the Schleizer-Dreieck road race, in which he defeated the entire BMW works team. He must have been a brave and skillful rider, considering that the Schleriz circuit contained more than a few wiggly bits. But it was in oval-track racing on dirt that the Megola really excelled, the qualities of FWD becoming more readily apparent in conditions where traction was at a premium. Being able to hang the rear wheel out, while keeping the throttle wound and the front wheel pulling, almost made such an odd idea worthwhile.

Not many Megolas have survived, especially not the Sport racing models. Having now ridden one, I can only say that Fritz Cockerell had both a warped sense of humour and a devious urge to create a motorcycling mutant. The machine seen here was apparently used to smuggle contraband in its pressed-steel monocoque chassis just after WWII. It was seized by the occupying forces and then sold off to an anonymous collector, who brought the bike to North America from Germany in partially assembled form, along with a spare engine/wheel assembly. Once in the US, it was assembled but never ran right, until 10 years ago when Pennsylvanian Jeff Craig was handed the machine for a full restoration. The Megola has recently changed hands and is currently owned by American comic and insatiable collector Jay Leno.

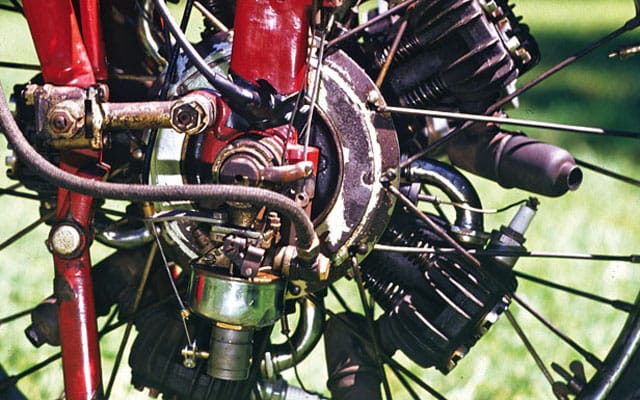

The Megola’s engine is often described as a radial design, but according to Craig this terminology is inaccurate. “A radial engine is one where the cylinders remain static but the crankshaft rotates, usually with a propeller attached to one end,” he says. “The Megola’s is a rotary, because the cylinders rotate and the bearing housing is stationary, in effect acting as the front wheel spindle. The same principle was used on certain WWI aircraft, like the Sopwith Camel and the Fokker Triplane.” The Wankel rotary differs from the Megola’s rotary design, the latter of which uses four-stroke principles. The Megola’s five side-valve cylinders measure 52 x 60 mm for a total capacity of 637 cc, and are disposed at 72 degrees to one another. The spokes of the front wheel are laced to the crankcase, so the wheel rim encircles the engine. For a racer, the only way to alter gearing was to re-lace a rim of different diameter. For this reason racers carried spare engine/wheel assemblies of varying rim diameters. Locating the engine in such an unlikely position assured ample cylinder cooling, but it presented challenges with fuel delivery, lubrication and exhaust design, with solutions that stamp Fritz Cockerell as a brilliant, if unconventional, engineer. With no clutch, the engine must be push-started and immediately ridden away once fired. The procedure is full of attendant risk, from the minor inconvenience of having your arms wrenched out of their sockets as the Megola catapults forward while you’re still congratulating yourself for having landed on the seat rather than the rear mudguard, to the major error of failing to ensure that the front wheel was pointing straight when you released the decompressor. If that happens, you’ll likely have one bar yanked out of your grip and rather ungracefully fall off.

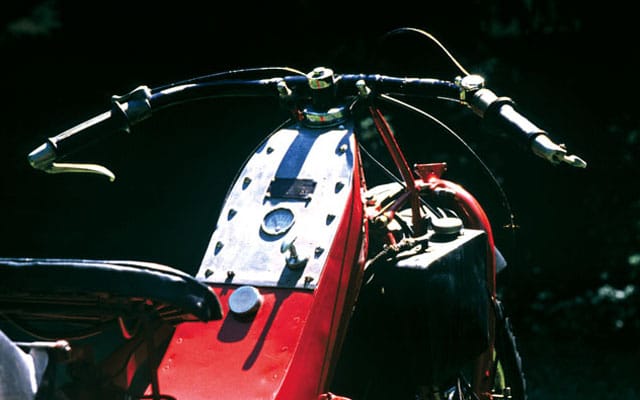

Touring Megolas produced a fairly lethargic 14 hp at 4,800 rpm; the more highly tuned Sport racer tested here delivers a reputed 25 hp at 6,800 rpm. Still, riding a Megola is daunting and winding it up is an unusual experience, even if only in a straight line. To combat the torque steer, a firm grip is required on the handlebar—presumably it turns better with the power on and the back wheel sliding behind you. But after grappling for an afternoon with the Megola’s pig-headed determination to have its own way exiting turns, I promise never again to complain about power understeer on a modern MotoGP racer. Engine lubrication is by total-loss gravity feed to the main bearings from a four-litre tank mounted on the left-hand steering strut. A corresponding tank on the other side holds a small supply of fuel, though this is only a priming tank, and must be topped up regularly from the main supply, which resides inside the pressed steel monocoque chassis, by means of a hand pump on the right side. Since the throttle is a lever type, it can be preset to maintain momentum while operating the pump. The front suspension is hardly worthy of the name and was apparently a weak point of the design. With the engine and front wheel suspended at the end of a small leaf spring, it was prone to fracturing.

The question remains: why build such a contraption? It requires many complicated— albeit ingenious—engineering solutions to problems that never existed until the designer himself created them. By 1920, the basic layout of the motorcycle was well established. Probably the only reason for the Megola’s existence is that Cockerell, who died in 1965, was simply a creative free spirit. At the time he probably thought the Megola more indicative of future two-wheeled design than the liquid-cooled inline four-cylinder bike he built in 1923. Only time, and the Japanese, proved him wrong.